Editorial Quick Take

Imagine two geological maps of your zip code, one made a thousand years ago and one made today. Chances are they would be nearly identical. Now imagine two road maps of the same area, one from 1965 and one from today. Could you find your way around? Probably. Finally, imagine two maps of your zip code, charting house color, one from 1987 and one from today. Would you recognize your own street?

This thought experiment gets at a couple of things. First, maps convey time as well as space. They tell us how things were. Second, there is a breakdown between the visible and the durable. This makes it difficult for mapmakers to show something that is both recognizable and stable.

For cities the solution to this has been the road map—street names are recognizable, street placement is stable, and streets are useful. The street map works so well, most people forget it is only one projection of a city—the godlike view from directly above—the plan.

The plan is easy to read and lasts decades. Initially used for strategy and infrastructure, it became popular in the eighteenth century and, by and large, we never looked back.

But if we did look back, we would see that there is a city map from a ninety degree difference—the view—basically a skyline.

Although the view won’t help us find anything, it gives a much better rendering of how things actually looked. It also tells us what was important at the time. For Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, mapping the great cities in the late 1500s, it was mostly churches and palaces that warranted notice.

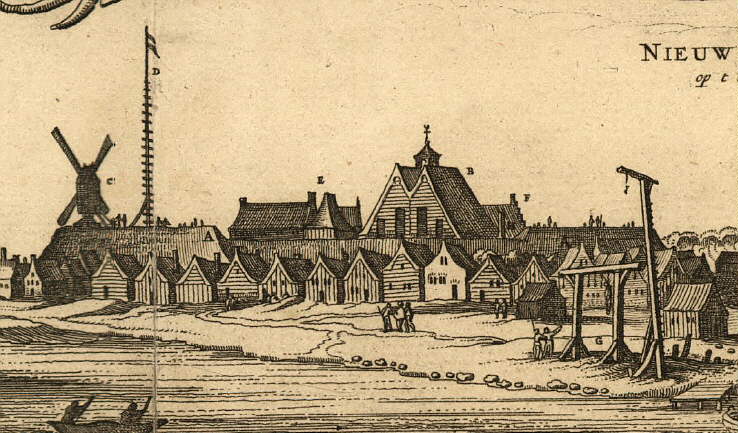

Looking at Manhattan (Nieuw Amsterdam) in 1656, this view is something different. We appear to be drifting down the East River. A sailboat and a canoe are close by and we are just about to round the point. In the foreground are a swath of brown water, a sandy beach, and steep-roofed, lap-board houses.

We see the fort, the church, the windmill, the warehouse, the gallows, and a flag—wert op gehaelt als daer Schepen in de Haven kom—which is raised when ships arrive. All told, it is not quite ramshackle, but certainly provisional, a foothold on a continent. We’re so close we can smell the dock and hear the gallows whine. And again, we get what’s important here: commerce, sea faring, and force.

The difference between the plan and the view is something like the difference between an X-ray and a portrait. One shows the underlying structure and the other shows a look in a given year.

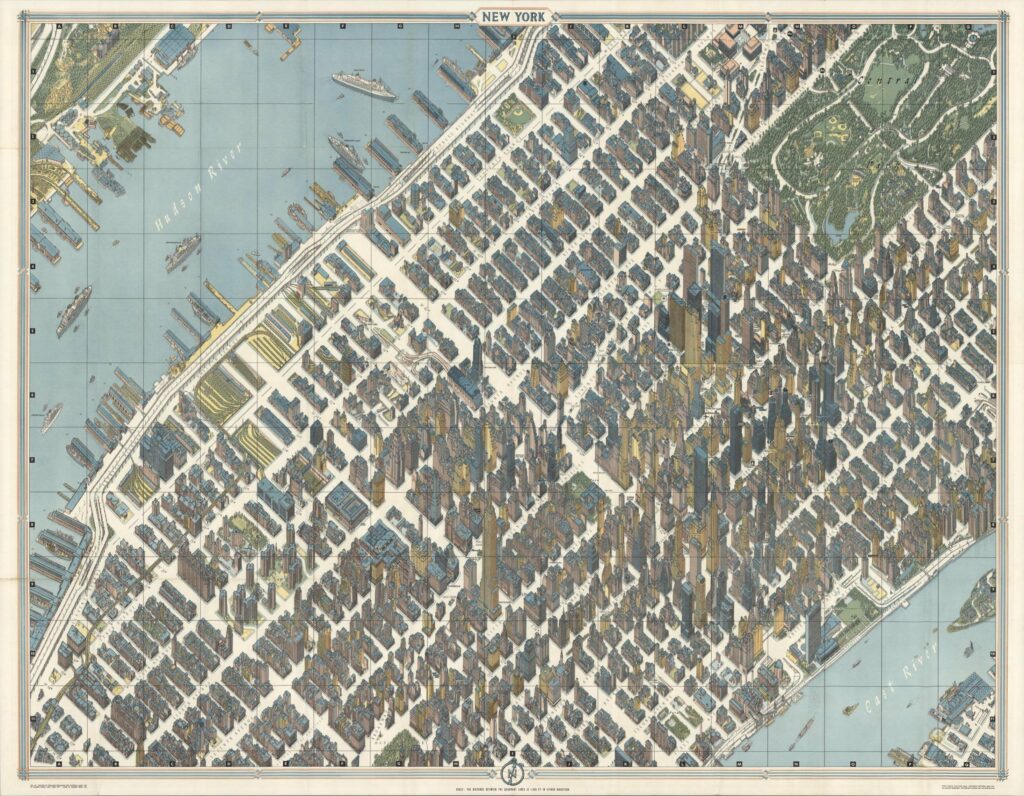

But there is a happy medium between the god’s eye and the human’s eye, and that is the bird’s. Projected from several hundred feet at a diagonal, it has the scope to take in a town, but is close enough to observe the colors of the roof tiles. And if it is done right, the viewer has a sense of falling from a great height, which is something we still pay money for.

Braun and Hogenberg offered scores of bird’s eyes, from Moscow to Cairo to Cordoba to London. Streets are visible but unmarked, buildings and rivers are named.

Thanks to a later pair, Parsons and Atwater, we can fly over Manhattan in 1875. Both rivers are teeming with steamships, and the blocks are packed so close that only Broadway can be distinguished. Like all good portraitists, the mapmakers cover some flaws. Brooklyn Bridge is shown finished, though it was under construction. The old Fort we saw in 1656 has become Ellis Island’s precursor—Castle Gardens. And there is a curvature to the projection, which lends a feeling of motion and plenitude and betrays that abiding sense that New York is at the center of things.

The bird’s eye kept some place after the triumph of the street map, though more in advertising than in navigation. Commissioned by the London Underground (tube) or the Shanghai Municipal Council, these maps tend to be fanciful and episodic rather than realistic.

Working as a cartographer in WWII, Hermann Bollman came across nineteenth-century Vogelschaukarten (bird’s eye maps). In 1948 he mapped his hometown that way, walking its streets with a sketchbook. Eventually he bought a VW and mounted a wide-angle camera. Mapping more than twenty-five cities, Bollman revised his maps to track a city’s changes. In 1962 Bollman took on Manhattan. Consulting more than 67,000 photographs—17,000 aerial—Bollman produced one of the great feats of a waning tradition. A vertiginous, blue-roofed metropolis the way it’s meant to be—without any traffic.

Though nothing can rival the plan’s usefulness, these other projections offer something else—taking a trip down the East River, or coming over a hill and finding Munich in the early evening. They offer the way places looked at a given time and what people found important. They may even allow us to imagine our own commute, crowded with anxieties, as it must look to geese high overhead, on their way somewhere else.

Enjoyed this Quick Take? Make sure you didn’t miss “Of Travelers and Itinera: From Jerusalem to Japan” and “Of Mappaemundi, Myth and the Material World.”

Header image: Bird’s-eye view of the city of Lisbon (Portugal) from Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg’s atlas Civitates orbis terrarum, vol. I, 1572 (public domain)