by Andrew Carr

I’ve been going out for long walks the last few days. As a teacher, the necessity of staying home from school has coincided happily with beautiful warm weather. Though I don’t always draw when I go out walking, I usually take a sketchbook with me. Even if I never open it up, having it along changes how I see. I start looking for the opportunity to draw. I see things as potential pictures. I certainly don’t want to see in that way all of the time. Sometimes I want to see things as themselves, not as the materials from which I might build something of my own. Sometimes it’s important to forget that I’m seeing things and just see them. Art, for all its insight, has a way sometimes of obscuring reality, of getting between you and the world. I’ve had the dreadful experience before—when listening to a dear friend tell me about some heartache or pain or difficulty—of thinking, in the very middle of the experience: “what an interesting short story this would make.” Even as the important moment unfolds I’m already impatient to make art out of it. I rush past the thing itself to get to the imitation.

All the same, having that sketchbook in my hand, or even tucked away in my backpack, gives my vision a certain purpose. I’m looking for something. And that persistent search at times helps provide direction and clarity in situations where a meaningful approach seems hard to come by. At times the goal of representation provides precisely the orientation needed to navigate a chaos of branches. Sometimes approaching an experience from the perspective of an unfolding narrative enables one to act with compassion and grace.

Anyway, there’s one particular walk that I took recently that turned out to be especially rewarding, that shed a particular and delightful light on this relationship between art and the world. I live in West St. Paul, close to Thompson Lake, which I’ve written on before. There’s a path that goes around that lake and then splits off, heads over the freeway, and follows the hollow of Simon’s Ravine down into the river valley. Part way down the ravine is another little path that jumps a small brook and then turns into old wooden stairs as it climbs up the hillside of the ravine.

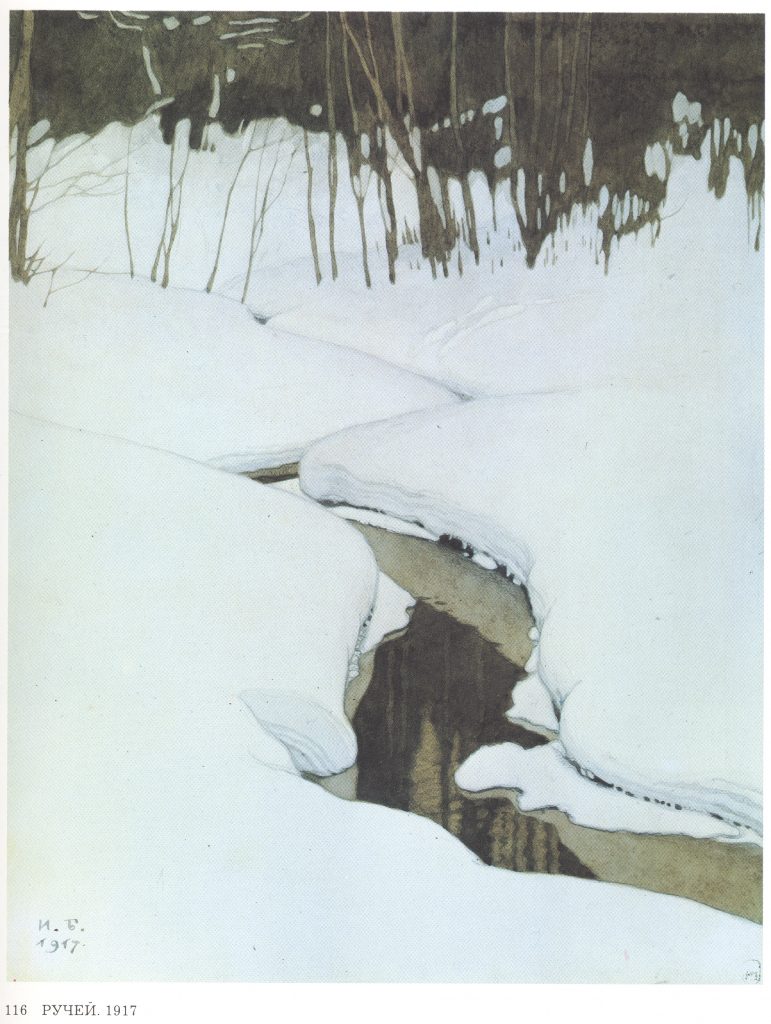

Last autumn, on a very sunny day, I took a piece of watercolor paper and went down to that spot to draw the stairs. It took maybe two hours. I worked in line, and focused on getting careful and elegant contours. By the end of my time, I was hot and sunburned, but very happy with the results. Over the winter I slowly turned that drawing into a watercolor. The lines were there, but I had to invent the tone and color scheme. I worked from memory, or else took aesthetic cues from other artists.

At certain points I thought I’d ruined my painting entirely. I showed the work in progress to a friend of mine, and he admired the way I’d drawn the snow. And I thought, “what snow? That was supposed to be dirt.” But then I got it into my head that maybe it should be snow. One of the paintings I’d been looking at for inspiration was a beautiful winter scene by the Russian painter Ivan Bilibin. And so I made the mistake of trying to have it both ways at the same time. Instead of sitting down and deciding exactly what I was after, I sort of tried to paint two versions of the painting on the same piece of paper, which got me into real trouble. When that happened I stopped, and for a number of weeks did nothing but look at the painting now and then until I could discover some way to proceed.

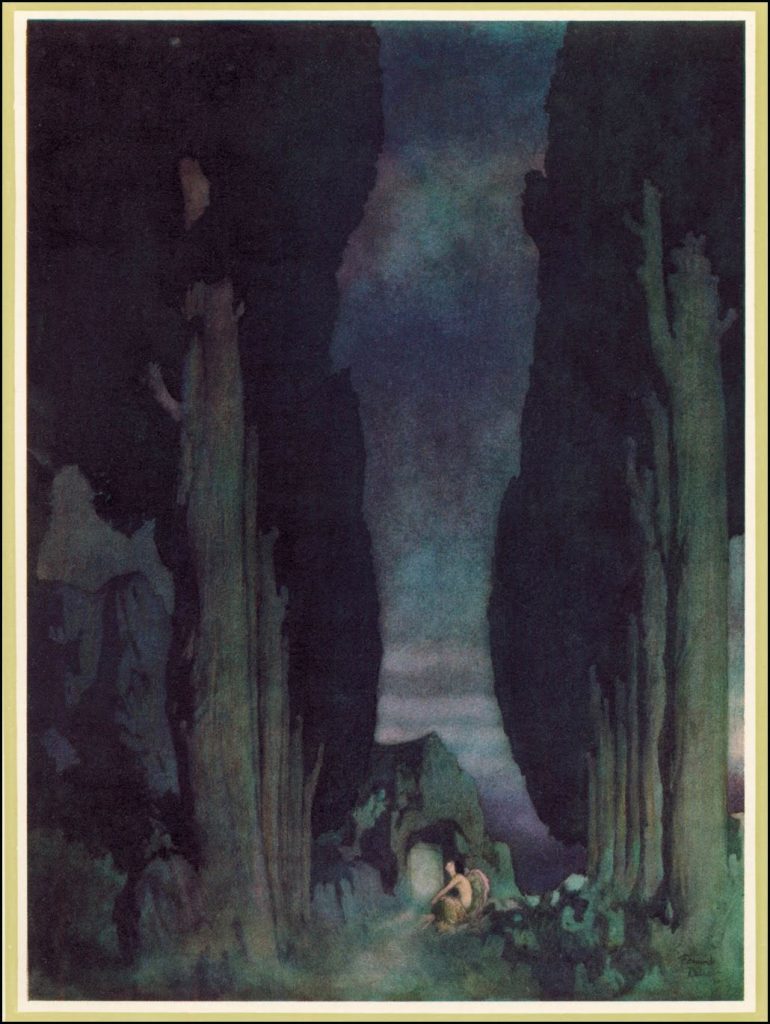

That way forward was provided by another artist I deeply admire, the Golden Age illustrator Edmund Dulac. Dulac had a penchant, particularly in the earlier part of his career, for painting these enchanting night scenes in rich and subtle variations of blue. And so my solution was to follow Dulac’s lead, and try to unify the conflict in my piece with a wash of blue over the entire image. And it worked. It was a little nerve-racking to transform the piece so dramatically, but it worked. I was able to continue.

Now, recently, after spending all winter looking into that landscape through the window of my painting, I decided to walk back down to that same spot. I sat in the very same place and looked into the real thing. I had drawn it very carefully and I was not surprised by what I saw or disappointed by the differences between the reality and my painting. Certainly there were changes. I had, of course, diverged in places. But on the whole, I was very satisfied with what I had done, and it was a pleasure to return to that place which I now felt I knew so well.

And then after sitting for a while, a marvelous thing happened. I got up, and walked into my painting. I walked over the bridge that I had drawn, and up the stairs that disappeared into the background of my composition. I watched my vision transform and unfold. The representation and the reality were somehow, strangely, wonderfully, superimposed upon each other. I walked all the way around trees that, for months, I’d been looking at from only a single angle. I stood inside their shadows, and I touched them with my hand.

Andrew Carr is a writer, painter, and teacher from St. Paul, MN. He loves cinema, short stories, and Saturday night jazz. He creates in the hope that his work might be as natural “As the cackle of toucans/ In the place of toucans.” You can find more of his drawing and painting at andrewgrumcarr.com.

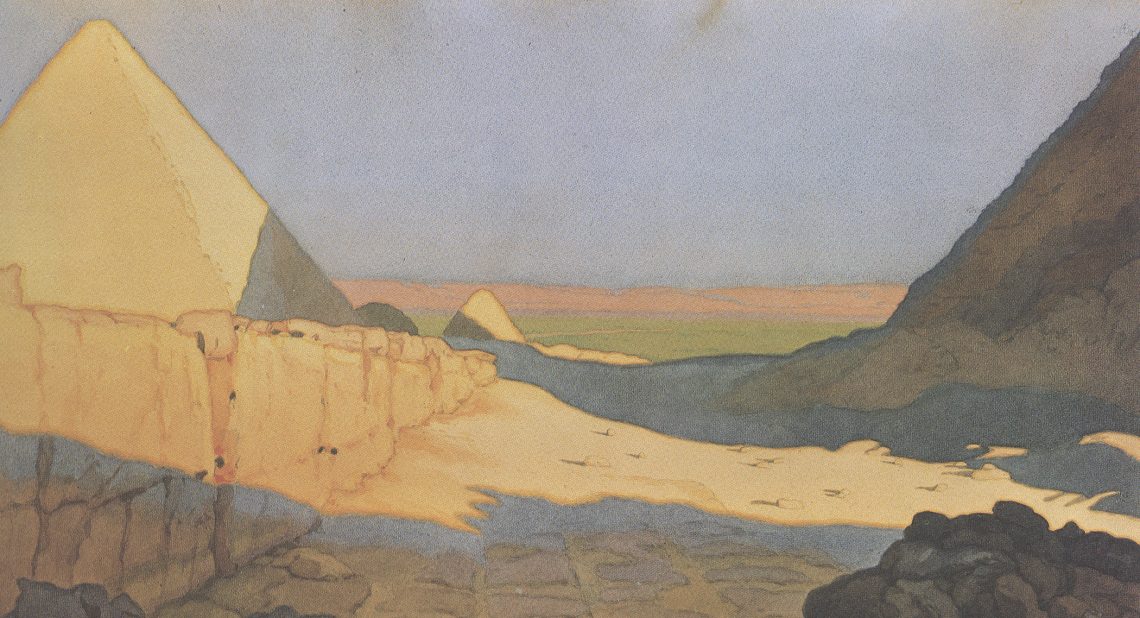

Header Image: “Egypt, Pyramids” (detail) by Ivan Bilibin, public domain

One Comment

Bridget Donohue

This reads like a powerful parable. I got sucked right into the painting along with the author. Wow.