by Benjamin von Bredow

“I am not an iconographer, but I know some iconographers.” So said the iconographer who introduced me to Orthodox icons, Symeon VanDonkelaar of the Conestoga Iconographic Studio. “That’s what my teacher said, and now that’s what I say,” he explained. Now I too, following my teacher as he did, say that I am not an iconographer—though perhaps I say so on much firmer ground than Symeon.

Why did my teacher, who regularly takes commissions for iconography and teaches iconography workshops, who spent five years in an Orthodox monastery training as an iconographer, draw back from saying the words, “I am an iconographer”?

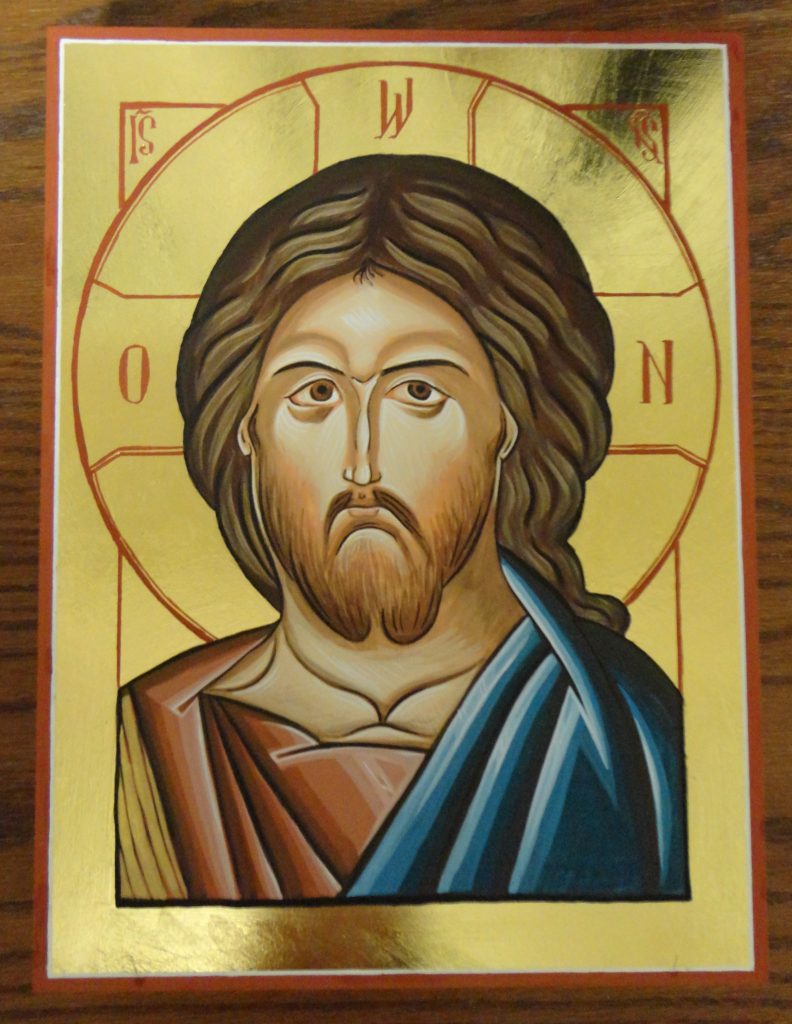

Symeon was invited by the chaplain of my undergraduate college to lead a five-day workshop with twelve students during the Spring semester reading break three years ago. A friend and I were both in the workshop, and we were so impressed by seeing the spiritual beauty of the icon emerging from the painted panel that we decided to purchase materials to practice iconography on our own. After a few weekend sessions, each of us had a second homemade icon up on the shelf, which is when we began to question the entire project.

An icon is a terrible and holy thing. You don’t just “look at” an icon. If it’s a matter of “looking,” it is more appropriate to say that the icon looks at you, rather than you at it. An icon is more readily compared to a door to heaven than a window: the presence of the holy ones—and above all of the Holy One of whom all holy things and people are images—bursts forth into the lower world through the door that the iconographer opens, revealing this world’s fragility and impermanence. This is why standing before an icon feels like being watched.

But an icon is a two-way door. The divine glory which shines forth from an icon, the “uncreated light” in Orthodox terminology, invites the worshipper to enter the world on the other side of the door. Honour, directed primarily to God as “worship” and secondarily to the icon itself as “veneration,” is the spontaneous response of the open heart to seeing the divine image. This worship is our attempt to “enter the door.” In our hearts we pass through the door by performing acts of self-abasement and praise.

Following Orthodox practice although we were not Orthodox ourselves, my friend and I put votive candles in front of our homemade icons. We crossed ourselves when we looked at them. We greeted them with a kiss. Therein lies the rub: what right had we to bow down before the works of our own untrained hands?

Our concern was not the iconoclastic one; we were not concerned that the production and veneration of icons is a form of idolatry. We were concerned that we were not rightly respecting a truly holy practice. If Symeon had to spend five years in a monastery before being released into the world as an iconographer and is still reticent to call himself such, what right had we, with five days of training, to paint a face and say, “This is a holy icon”?

Iconography is not a “creative” discipline. Its purpose is not to bring something new into the world, but to reveal what was always latent, to reveal the material world’s capacity to be made a vessel of divine grace. A good iconographer will develop a method and a visual style, but that style can never err too far from the traditional norms for depicting certain saints and events. Icon textbooks frequently say that naturalism, especially when it is paired with divergences from the traditional symbolic elements of a scene, is “Western,” “sensual,” and “unspiritual.” On the other hand, extreme anti-naturalism can err in the direction of the cartoon-like and ridiculous, and iconographers also try to avoid this tendency. Orthodox tradition allows a relatively narrow range of styles, and defines the symbolic content of “canonical” icons very strictly. New elements are only invented for icons of modern, Western, or little-depicted saints.

My friend and I were very self-conscious of how entirely we stood outside that tradition. At that point, neither of us had ever attended an Orthodox liturgy. We had only a few Orthodox friends, but we had never discussed iconography or theology with them at any length. Some writers would say that only Orthodox people are allowed to even attempt iconography, and only with spiritual counsel, and we were Anglicans. If we didn’t know the relevant Orthodox traditions, we thought, surely we would err from them in the production of icons. And if we did err from the tradition, what could the claim, “This is an icon,” possibly mean—except, of course, as a vainglorious boast?

We kept right on writing icons. (Some iconographers insist on calling it “writing” instead of “painting” because what is depicted is a word, the divine Word, shining forth in the person of the saint represented.) Symeon was very supportive, and threatened to call in ecclesiastical authorities in support of us should any Orthodox person object to our impiety. But we kept on feeling ill at ease.

As one would expect

The experience of constant error was humbling, but in our

Iconography is all about the Incarnation. God the Word can be depicted because he took flesh in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, a physical person with the sensible likeness. Appearing in the flesh, the Word sojourned among us ultimately to go to the cross, to be abused at the hands of the sinners for the sake of their salvation. The Word did not come in flesh to be worshipped by the discerning, but mistreated by the block-headed and foolish who “know not what they do.”

Here, the incarnational themes of soteriology and iconography coalesce: the Incarnation invites us to recognize that we are too broken to do anything to Christ except violate his image, just as the image of God was violated upon the cross. We violate afresh God’s image written on our own persons every time we sin. God calls us while we are still sinners so that, at very least, we might understand what we are doing when we crucify him, and so that we might understand that he wants us anyway.

I am a sinful man who does not merit the grace to depict his God, and I am filled with the fear and trembling at the fact that I am called to do so nonetheless. Even if I were a more professional painter, my condition would be the same: I would still be dust and ashes, capable of worshipping God only by a gift of his grace.

I now understand why Symeon said that he was not an iconographer. One can never claim that the worthiness of one’s own art has compelled God to be present in a painted image. Indeed, all that we can claim about our own art is that it falls short of divine glory.

But, in the great mercy of God, the God who became incarnate in human weakness, he regularly makes unworthy icons into sacraments of his presence. In his mercy he also calls unworthy people to be the vehicles of this image-incarnation. A talented artist is not an iconographer by virtue of his art alone, nor is an iconographer-saint an iconographer by virtue of his holiness. An iconographer is a sinner saved by the miraculous appearance of God in the flesh.

Benjamin von Bredow is a Master’s student in liturgical theology at the University of Notre Dame. He is preparing for Anglican ministry, trying to “go pro” as an iconographer, and generally pursuing too many hobbies to get very good at any of them.

One Comment

Sister M. Leonarda Nowak. F.D.C.

We have a beautiful icon of Saint Mary Magdalene, from Greece, could you please help us identify the iconographer? Here is the signature on the icon:

I cannot get the photo to appear here. I will try to send it separately now. Thank you. God bless you