Editorial Quick Take

Heads up. This may not be the history you were expecting. The contentions surrounding concepts of sex and gender may be among the defining issues of our time, but they are not suited to a quick take.

Rather, this article will take a brief look at the linguistic history of the words “sex” and “gender”—fascinating in and of itself. And, along the way, it may even shed some light on the contemporary debates.

The words “sex” and “gender” both first appeared in the English language in the dynamic second half of the 14th century. Both words have their roots in French but were established during the rise of what we now call late Middle English.

The Oxford English Dictionary’s first citation of “sex” in the English language comes from the earliest version of John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible into English. He translates God’s command to Noah in Genesis 6:19: “Of all þingez hauyng soule of eny flesch: two þou schalt brynge in to þe ark, þat male sex & female.” (“Of all things having soul of any flesh: two thou shalt bring into the ark, that male sex and female.”) In his later and more widely accepted version, Wycliffe swapped the word “sex” out in favor of the more Germanic “kynde.”

Fascinatingly, when “gender” originally entered the language, it had nothing to do with sexual difference. “Gender” was used either as a grammatical term or as a substitute for the scientific word “genus.” Then in the 15th century, the word was extended from its grammatical sense to its biological sense. Once that extension took place, English had two words for sexual difference.

Then things got a little weird. In the 17th century, “sex” began to be used to describe not only biological difference, per se, but also differences between male and female other than strictly biological ones. Addison and Steele’s The Spectator, for instance, contains this treatment of sex:

WOMEN in their Nature are much more gay and joyous than Men; whether it be that their Blood is more refined, their Fibres more delicate, and their animal Spirits more light and volatile; or whether, as some have imagined, there may not be a kind of Sex in the very Soul, I shall not pretend to determine.

From the 17th century on, then the word “sex” could be used in English to describe males or females biologically, or it could be used to describe something more ephemeral.

It wasn’t until surprisingly late that “sex” became a synonym for “intercourse.” Though that is now the most often used sense of the word, the first occurrence of its usage in the OED isn’t until 1899. As this usage picked up, there was a significant chance of confusion or even embarrassment. To avoid such confusion, “gender” gradually began to replace “sex” as the preferred term to differentiate between males and females, and “sex” took on a tinge of vulgarity.

A few decades later saw the last major evolution in these two terms — and the one that continues to cause us trouble today. Some mid-20th-century sociologists and psychologists began using “gender” not to talk about sexual difference but to talk about the expression of sexual difference in a culture. Some even went so far as to say that “gender” was only a social construct. When these definitions took hold, the roles of the two words pretty much flipped. There is still some ambiguity and overlap, but “sex” is now the word most commonly used to describe a biological distinction between men and women. And “gender” is used to describe the psychological and sociological differences associated with sexual difference.

Is knowing the complex history of the words “sex” and “gender” going to solve the contemporary debates around sexual difference and society? Probably not. But words do matter. Knowing their history just might help avoid misunderstanding at the critical juncture of some important conversation. We could certainly do worse than begin with clear definitions.

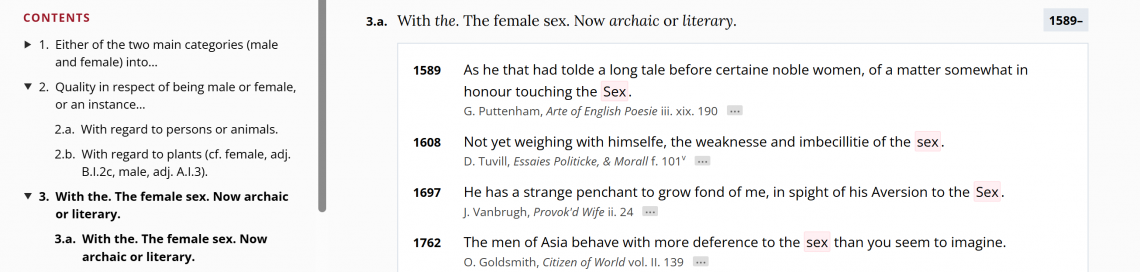

Header Image: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/sex_n1?tab=meaning_and_use#23485890 , accessed 9.24.2025 used in keeping with fair use.