“Liberalism Is Worth Saving. Just Ask Its Critics,” by Zack Beauchamp in Vox

With postliberalism looking increasingly unattractive, and the left offering no clear and compelling alternative to liberalism, liberals have an opening to reinvent themselves. Such a new liberalism would not merely attempt to rebut its opponents or “defend democracy” from Trump, but rather develop a new articulation of its own ideas to address modern problems.

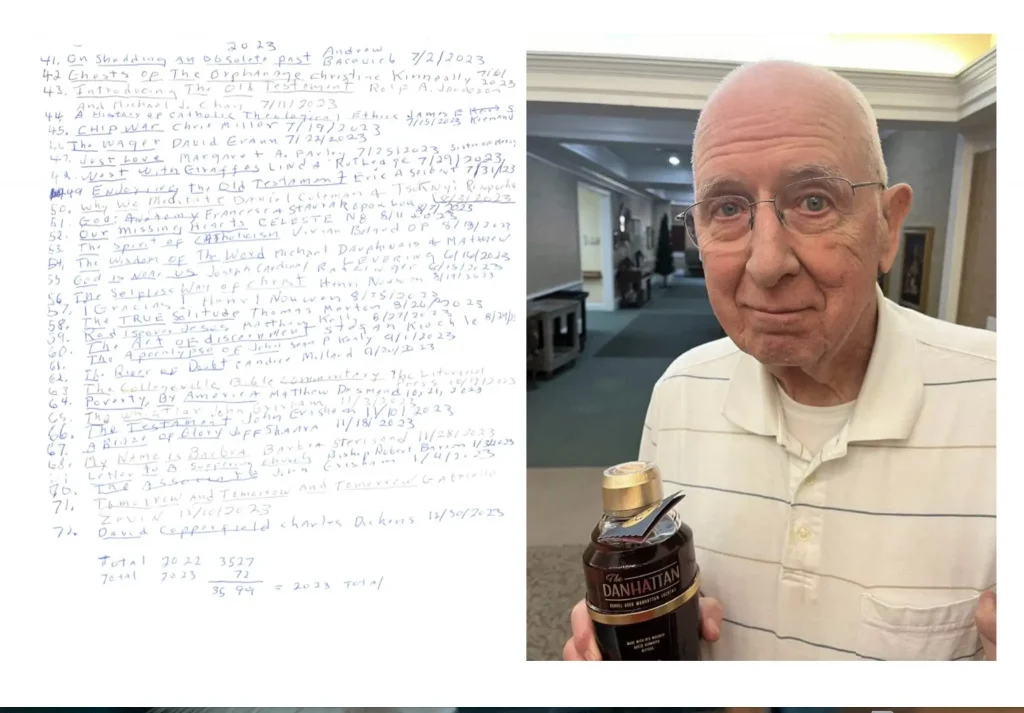

“He Read (at Least) 3,599 Books in His Lifetime. Now Anyone Can See His List,” by Aishvarya Kavi in The New York Times

He did not enjoy the nearly 1,000-page “Ulysses” by James Joyce, nor L. Ron Hubbard’s “Mission Earth,” a 10-volume science fiction series published in the 1980s. But once Dan Pelzer set his mind on reading something, he did not put it down until he was finished.

That’s how Mr. Pelzer’s children said he was able to read 3,599 books from 1962, when he first began jotting his reads down on his language class work sheets while stationed in Nepal with the Peace Corps, to 2023, when his eyesight failed him and he could no longer read.

“Math Is Erotic,” by Matthew B. Crawford in First Things

J. Jacob Tawney, in his new book Another Sort of Mathematics, writes that there are “some things from mathematics that you should experience.” What an odd and arresting way to open a book about math. It is not the sort of exhortation we are used to hearing from the STEM-winders-and-grinders who push math for the sake of economic competitiveness, critical thinking skills, or other ends extrinsic to math itself. For Tawney, there is something beautiful and important to be experienced. He comes to us not as an “educator” in the dreary, institutional sense of that word, but as an evangelist.

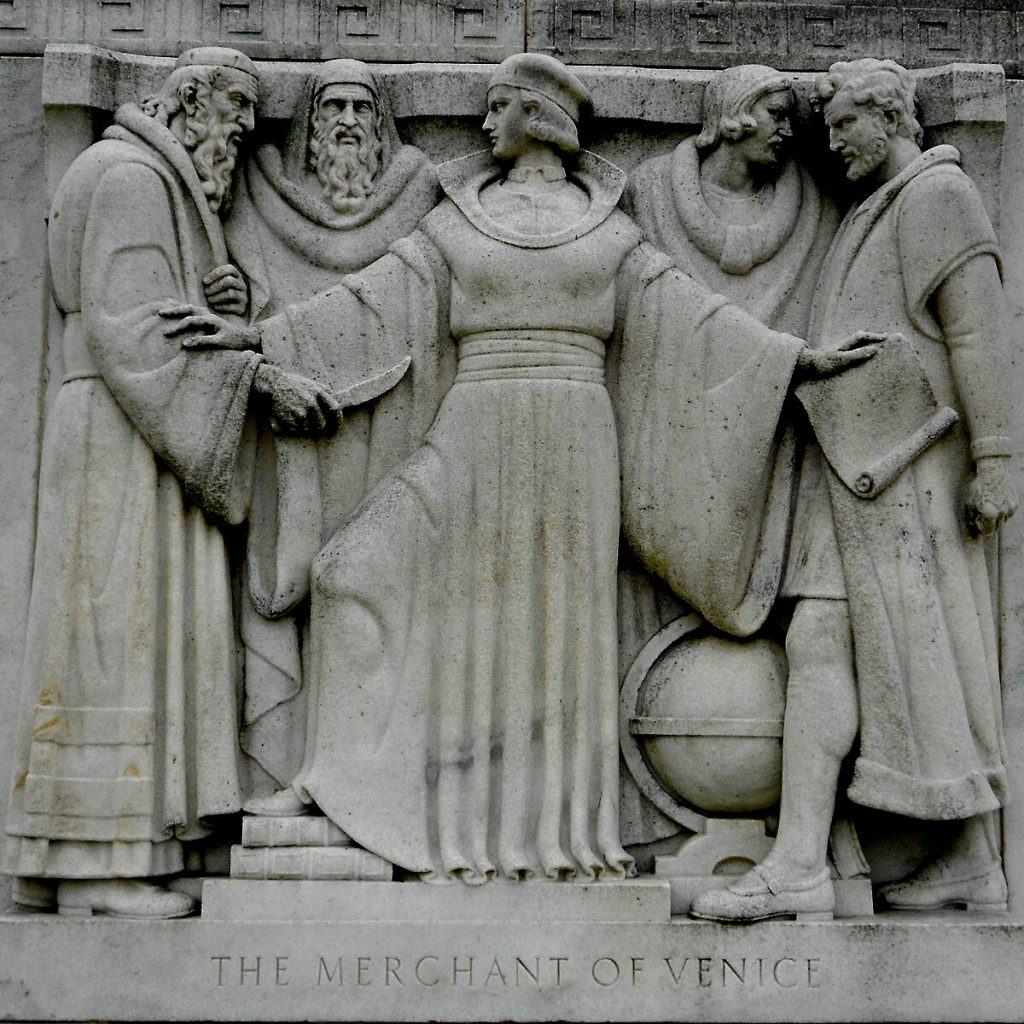

“How Do Books Work in Our Classrooms?” by Chris Schlect in Classis

The teacher in the first classroom engages her students through her charisma. She roams her classroom and reads key passages aloud. She brings the text to life with her lively recitations—or we might even call them performances. By her magnetic presence, she draws her students into lively discussions. She stirs them with her lively rendition of Shylock’s demand for vengeance in Act III, and again by Portia’s soliloquy on mercy in Act IV. She pulls her students into the drama; they identify with the characters, see the weight of their circumstances, and develop a healthy appetite for virtue. This charismatic teacher forms her students into lifelong lovers of Shakespeare, just as she is.

Now we turn to the second classroom and another cohort of 10th graders. Here we encounter a more analytical teacher. This teacher highlights ways in which The Merchant of Venice raises timeless ethical issues. He steers his students toward fundamental ethical questions: If justice is giving a person his due, then how does mercy figure in? Is mercy inherently unjust? How shall individuals balance their ethical duty to family, to community, and to their fellow man? This analytical teacher uses the text to draw out eternal principles that speak to universal questions about the good, the true, and the beautiful.