Quick Take

Did you wake up Christmas morning to an orange in your stocking (be it chocolate or the original fruit)? Publishing Luke Sawczak’s wonderful little poem “Citrus” so near the holy day got us thinking … Why oranges at Christmas?

It turns out that the pungent fruit is intimately wrapped up with stockings, gold, dowries, and good old St. Nicholas himself.

Like so many of our beloved Christmas traditions, both stockings and the oranges we put in them originate in the 19th century.

In a time when the sun never set on the British Empire, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert brought the German tradition of Christmas trees to the entire world.

Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol with original illustrations by John Leech, helping “the spirit of Christmas” cross the sacred-secular bridge.

“Sinterklaas” became “Santa Claus.”

Washington Irving gave him his sleigh.

Thomas Nast’s 1862 illustration for Harper’s Weekly fixed his image in our collective imagination.

And an originally anonymous poem provided him with eight reindeer (complete with names), moved Santa’s gift-giving day from December 5th to December 24th, and gave us one of the most recognizable couplets in the English language:

’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

But the late Victorian Age was also an age of growing religious skepticism, and in 1897, a young reader wrote to a New York newspaper, The Sun, with a question:

Dear Editor,

I am 8 years old. Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus. Papa says, “If you see it in the Sun it’s so.” Please tell me the truth, is there a Santa Claus?

Virginia O’Hanlon

115 W. 95th St.

The paper’s response began:

Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age. They do not believe except they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men’s or children’s, are little. In this great universe of ours, man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no Virginias. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.

The entire editorial, revealed after his death to have been written by Francis Pharcellus Church, is worth reading for any number of reasons — cultural, philosophical, theological, cultural-historical, historical-philosophical … You get the point. But for one reason or another, or probably many, by the time the defense of Santa appeared in the pages of The Sun (where it would be republished every year until the paper’s demise), our modern Santa Claus was well-established and largely protected in the mythic imagination of most of the world.

However, the oranges (and the stockings) go back further to one of the original stories of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, Bishop of Myrna.

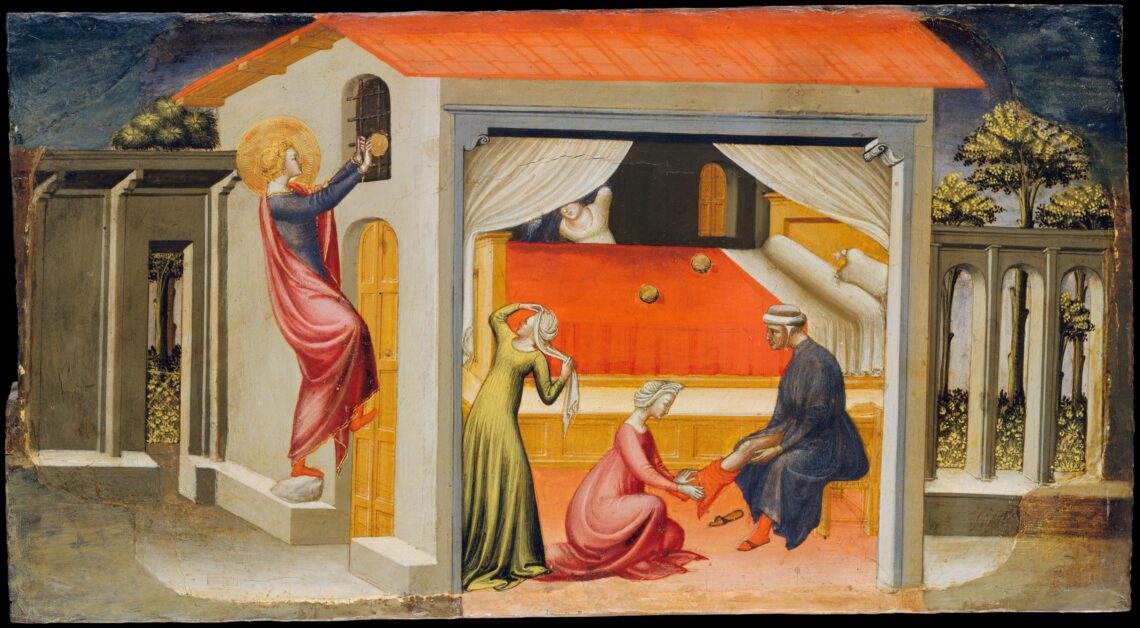

As the story goes, there was a man with three daughters, all of the age to marry. The man had once been wealthy, but had fallen into poverty. So there was no dowry or anything of value to offer future husbands who might propose to his daughters. Without any prospect for marriage, the daughters were in danger of slavery or worse.

Nicholas, who had inherited wealth from his parents, heard the sad story of the man and his daughters. At night, he came in secret and tossed through the window what in some tellings is described as a “ball of gold.” The gold accidentally landed in a stocking hung up to dry, but in the morning the gold was discovered in the stocking. The first daughter had her bride price!

On the second morning, a second ball of gold was found, and the second daughter was able to marry.

Desperate to know the name of their anonymous patron, the father finally decided to keep watch at night hoping to catch the gift-giver. When a third ball of gold landed inside the house, the father leaped up and caught the good bishop at his work.

Embarrassed and not wishing his deeds to be known, Nicholas asked the man to keep his identity secret. “Thank God alone,” he said, “that he has answered your prayers for deliverance.”

Of course, the scarcity of citrus in some parts of the world and their vibrant color make oranges an obvious stand-in for real gold in most of our homes.

So whether you sank your teeth into the tart goodness of clementine this Christmas or cracked a chocolate orange on the counter, remember both the charity and humility of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker.

Merry Christmas from Veritas Journal

Header Image: Bicci di Lorenzo (Italian, 1373–1452). Saint Nicholas Providing Dowries, 1433–35. Tempera and gold on wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Coudert Brothers, 1888 (public domain)