by Andrew Grum Carr

The Minneapolis Institute of Art is open late on Thursdays, and my brother and I got there in the early evening. Outside, spring was finally arriving. It was the Thursday before Easter, and the birds were chattering excitedly about how warm it was getting. But inside the museum was quiet and still. I’d recently discovered a rack of small, rarely-used folding chairs by the elevator, so we each took one, and though we hardly sat at all, we enjoyed carrying them with us as we wandered around.

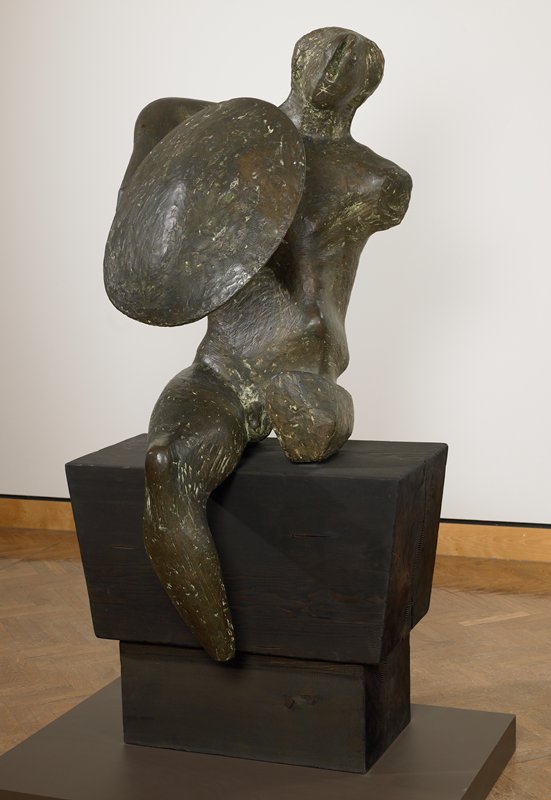

Eventually we found ourselves in front of a piece we had never seen before, a statue on the third floor, by the 20th-century sculptor Henry Moore, Warrior with Shield. Among colorful work by Kandinsky, Matisse and Kirchner, the large bronze figure sat unsteadily on two blocks of blackened wood, the bigger block stacked upon the smaller, so that they resembled an anvil. And in fact, it almost seemed to us as if the warrior had been newly forged on this scorched bench–except that the pose and the form seemed less to indicate a moment of creation than one of destruction and loss.

The warrior’s shield was held out as if to resist some terrible force, a force against which the whole posture braced. And wherever the shield failed to cover, wherever the body remained exposed, it had been annihilated. The left arm all the way to the shoulder. The left leg up to the pelvis. The right calf terminating at the ankle like a piece of driftwood. As we looked, we were painfully aware of just how much body struggled to hide behind such meager protection.

The idea of driftwood came to mind because–though the surface of the statue was pockmarked, scratched and pitted–the limbs didn’t seem severed or mangled, so much as ground down, worn away as wood or stone is worn away by water or weather or time. For that reason the statue seemed to occupy two time frames, one brief, one prolonged. Both the violent instant, the impact of a blinding light, an obliterating moment of force–but also the slow duration over which the supposedly permanent is steadily, patiently effaced. I once read a placard along the Mississippi river that explained how waterfalls gradually crawl upstream. The constant pounding of the water hollows out the underside of the ledge until the overhang finally collapses and a new ledge is formed, slowly advancing the falls over hundreds of years.

My brother lives up north in Duluth, but was staying in the Twin Cities for a few days, with our parents. He was having surgery on Monday, at the Mayo Clinic, and wanted to spend Easter with our family. He had been losing hearing in his left ear, and about a year ago he went in for testing and learned that he had a benign tumor on his auditory nerve. His options were either surgery through an opening made in the back of the skull or radiation. He seemed to consider each possibility calmly and carefully, eventually deciding on surgery. Because of the sensitivity of the nerve, there was a fifty percent chance that the operation would destroy all hearing in that ear. A coin flip.

The day before, in our parent’s kitchen, I asked him how he was feeling about it all, if he was anxious. And he said not really, that he was fine. Between the initial tests and the specialists and everything it had all happened gradually enough. He’d had a chance to come to terms with things by now. And he really did seem pretty at ease, pretty matter of fact. He told me that he’d searched online for a list of the best stereo albums of all time and had been listening to a handful of them over the last few days, but was mostly disappointed. I didn’t know if there was much more to ask or say.

But the trip to the museum turned out to be a way to sort of continue that conversation by other means. To approach things obliquely. I’d gotten to the museum before him that Thursday evening and waited at the café just inside. I was sitting drinking a coffee when he came in, but hardly recognized him at first because he’d buzzed off all his hair. Only later, looking at Moore’s statue, did I put together that he’d cut it for the surgery.

The statue’s own head was small, on a thick neck. It resembled an obscure piece of industrial machinery, an old iron lock or pulley, through which you might thread a steel cable and lift the entire sculpture with a crane. The eyes were an entrance on either side of the head, to a tunnel that ran all the way through. If you tried to look into them, instead of looking in, you looked right out the other side, at a hole-punched circle of white gallery wall. The mouth was a shallow asterix scratched beneath. If the limbs had been annihilated, the head had been exposed. All the familiarity blown away, leaving behind only this skeletal machinery underneath. A structure which nevertheless remained deeply sympathetic.

The statue itself was troubling, but looking at it together, sharing observations and associations, was pleasant and intimate. Conversation about a good work of art manages somehow to sit halfway between the vulnerable work of personal disclosure, and the low stakes of casual conversation. By the time we moved on, it was with a sense of satisfaction. Not at having “solved” the piece, or because we had articulated some comprehensive interpretation. And not because the statue’s sense of loss had been alleviated–if anything it had deepened. The satisfaction came from the feeling that we were, all the same, at least better acquainted with this figure sitting there on the bench.

That next Monday my mother texted me that the procedure had gone well, but that my brother had lost all hearing in his left ear. The tumor had been removed and the nerve was intact, but the signal had gone dead during the operation. It was there and then it wasn’t. There was also some initial facial paralysis, and we would have to wait to see how his balance had been affected. The doctors were all confident that the paralysis would resolve itself in a few days, but the hearing was gone.

When I visited him on Wednesday he was in bed, watching the Twins game, but paused to show me the long row of staples on the back of his head. I happened to catch him during a brief window of relative relief. The first twenty-four hours out of surgery sounded dreadful. They struggled to find the right balance of medications to get the pain under control. He kept vomiting, and every time he did all the muscles in his head would tense. He was exhausted but only allowed to sleep for short periods of time so that they could monitor brain function. And after his release from the hospital a few days later his recovery seemed to regress, and he spent the following month in his Duluth apartment, plagued by relentless nausea and vertigo.

During my visit though, things were calm and fairly comfortable. He had slept well during the night. He had started getting up out of bed again. His balance was beginning to re-calibrate. When we went for a walk together along the hospital corridor, he wore a thick blue belt around the waist of his gown so that if he fainted and went limp I would have something to grab onto to help lower him safely to the floor. He practiced turning on a point, and tried to walk along a certain pattern in the floor tiles as if it were a tightrope.

As we walked my brother told me about the first night, while he was still in the intensive care unit. He was scared and disoriented and didn’t want to spend the night alone. He was told that visitors were not allowed to stay, but his girlfriend had stubbornly refused to leave, until their nurse, who was awkward and conflict-averse, eventually just decided to look the other way. To conclude our walk, we went to the stairwell and he practiced going up and down. By then he was worn out. As we made our way back to the room I mentioned the statue again. It made me think of him, though I couldn’t really explain, and felt sheepish about saying it. I was worried that it might seem inappropriate or pretentious. But he agreed right away. He seemed to share the intuition. That was all we said about the statue. But in the midst of everything, I found it somehow reassuring.

Andrew Grum Carr is an artist, writer, and teacher from St. Paul MN. He writes short fiction and works in watercolor. He loves cinema, the library, and Saturday night jazz. You can find his artwork at www.andrewgrumcarr.com or follow him on Instagram @andrewgrumcarr.

Header Image: “Warrior With Shield,” (2008), © Jon Balsbaugh, Kairos Photography

In Text Image: “Warrior with Shield,” © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2014 / www.henry-moore.org (used in keeping with fair use)