Editorial Quick Take

A previous quick take introduced readers to the itinerary, a map designed to show you how to get there. But maps have never been restricted to certainties. Mapmakers throughout the centuries have also ventured to say not only what they knew, but also what they believed. From Egyptian afterlives to images of Africa made in feudal Korea, from Ptolemy’s Almagest, to NASA’s images of Mars, maps have always been attempts to situate us in the universe.

Of course, every map is inevitably reductive and inadequate. As one medieval geographer admits, “If the page had allowed it, this whole island would have been longer.” When it comes to maps and reality, there is simply too much to get in. But maps can perhaps succeed in suggesting what is important. What is important about a place — its topography, history, global position or even mythical value?

Mapmakers in every major tradition are divided on this. Some seek to deal only in material reality. Others attempt to communicate humane, historical, or religious importance.

We have Babylonian maps dating back to 2300 BC that show specific streets, rivers, property lines, mountains, and canals. But even earlier maps ignore this pragmatism, opting instead to trace the contours of an entire cosmology — the known universe: a flat world bisected by the Euphrates and bounded by primordial waters, a huge rectangular Babylon at its center.

A similar tension exists in Islamic cartography. One of its classic works, Muḥammad Abū’l-Qāsim Ibn Ḥawqal’s Picture of the Earth (1086 AD), takes the cosmological approach. Hawqal’s world map is an abstract portrayal of the Islamic worldview, circular, oriented south—out of reverence for Mecca—with holy Kaaba at its center. The map also includes a great red Nile and a foreshortened Europe at the bottom, bounded by waters and mountains. This rendering is not a function of ignorance. Ibn Hawqal traveled extensively and was familiar with Ptolemy. Rather, Hawqal is working from within a consciously Islamic aesthetic, established in the tenth century by the Iranian cartographer al-Balkhi.

A near contemporary of Hawqal, al-Idrisi, shows a more physically faithful alternative. He also orients his maps south, but his 70 section world map is compiled from Ptolemy’s commentary and information gathered at the Christian court of Roger II.

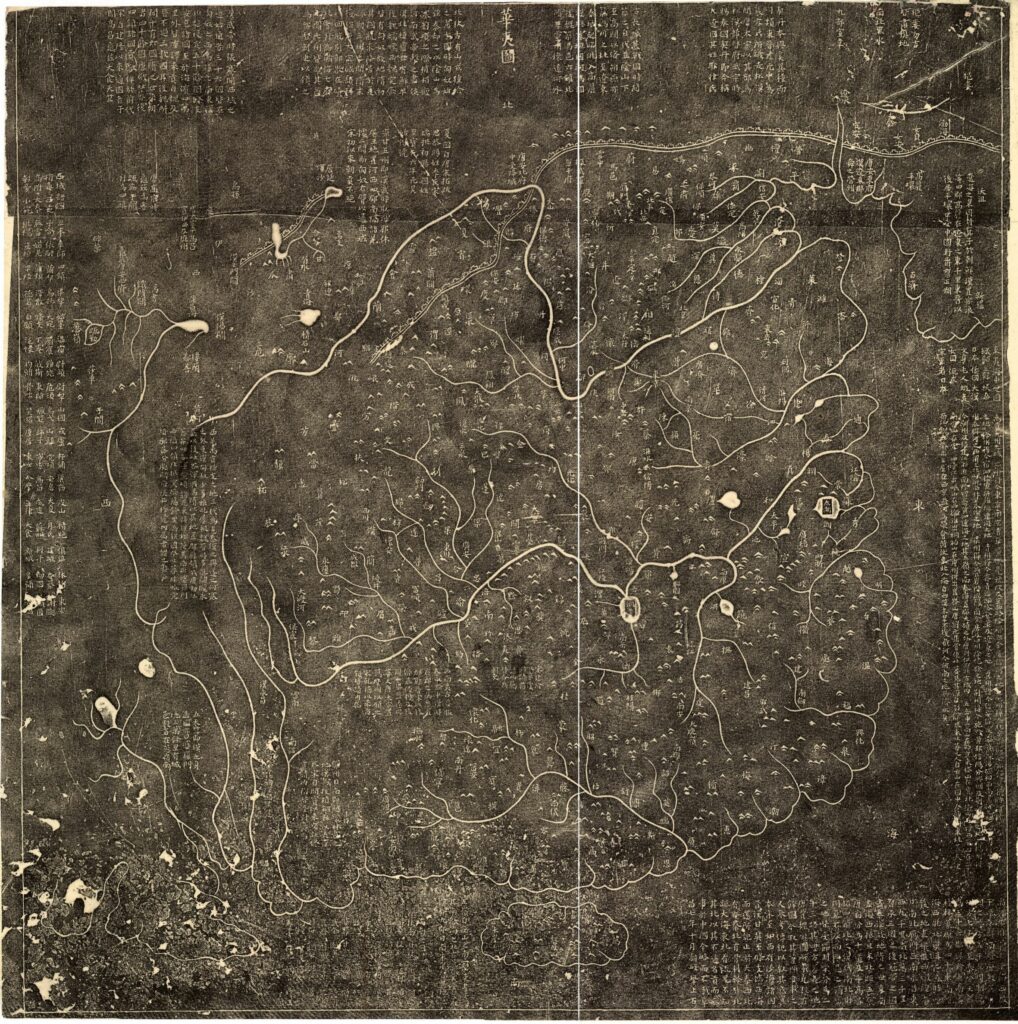

The same pattern holds in Asia. The Yu ji tu offers an image of China some time before 1300 AD. Strikingly modern, the Yu ji tu is overlaid with a grid indicating scale. It describes the coasts, towns, rivers, lakes, islands, and mountains in detail that approximates modern maps. Yet a fourteenth century copy from a Chinese map sets aside any attempt at physical accuracy. Instead it portrays the world as an egg-shaped disc surrounded by waters. Its world is, in fact, the subcontinent of India, divided into five provinces, with Mt. Meru—home to the god Indra—as an unraveling concentric circle at its center. The Gotenjiku Zu (Map of the Five Indies) was copied by the Japanese Buddhist monk Jukai, and traces the pilgrimage of the Chinese Buddhist priest, Xuanzhuang.

In the West, medieval world maps (mappaemundi) appear in prayer books as flat disks, bounded by the ocean, with Jerusalem at the center. The commonalities between Babylon, ibn Hawqal, Jukai, and Isidore are notable. Each of these maps is a circle, with the sacred reality at its center, enclosed by unknown waters.

As the ‘age of exploration’ dawned and advances were made in surveying, the West largely abandoned its mappaemundi. Today material importance seems to have won out. But at the cusp of the modern era in the West, Cresques (son of) Abraham, a Jewish cartographer in Palma, made one last great attempt to hold together the material and the cosmological in a single world map. His eight panel masterpiece portrays coastlines in terrific detail. Exact colored rhumb lines demarcate the world. But a variety of images on the inland portray a more human value. Alexander the Great conquers alongside a black-winged Satan, Muhammed kneels in Mecca, Christ the King teaches his apostles in Asia, and massive Chinese vessels ply the oceans.

With advances in computer imaging, the most materially faithful maps have become increasingly abstract. But might it still be possible to marry the materially faithful with the spiritual significance in cartography?

Enjoyed this Quick Take? Make sure you didn’t miss “Of Travelers and Itinera: From Jerusalem to Japan”

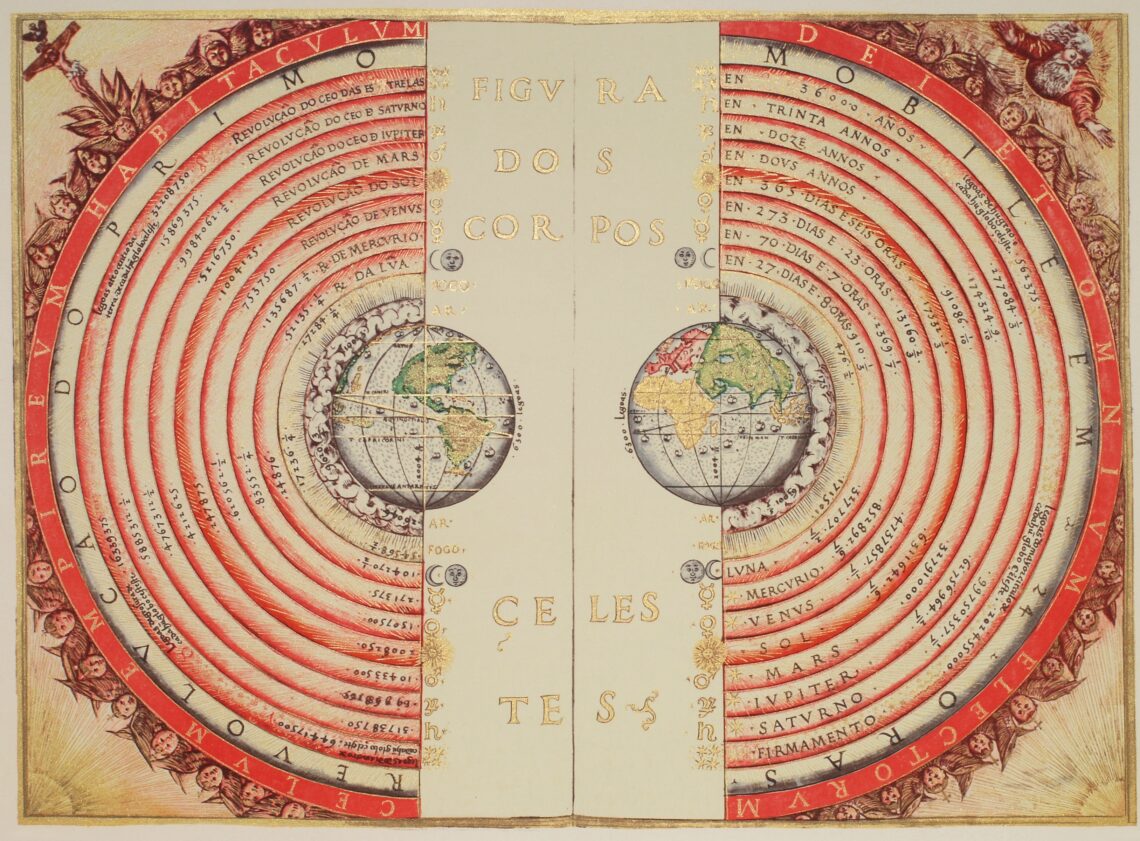

Header image: “Figure of the heavenly bodies,” Illuminated illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric conception of the Universe by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho (?-1568). From his work Cosmographia, made in France, 1568 (Bibilotèque nationale de France, Paris). Notice the distances of the bodies to the center of the Earth (left) and the times of revolution, in years (right). The outermost text says: “The heavenly empire, the dwelling of God and of all of the elect” (public domain, description adapted from Wikimedia Commons).