“White Buffalo,” a memoir by Christian Wiman in Harpers Magazine.

I should have realized that a person who can find Christ in hell, as my sister did in that prison, who can see Christ working in hell and love this work even as that balm is withheld from her, is not a person whose soul is dead. Why must I learn the same lessons over and over again? That both life and art atrophy if they are not communing with each other. That it means nothing to make a space for the miraculous in one’s work if one can’t recognize some true intrusion in one’s life.

“Christian Humanism: An Invitation to a Truer Story,” David Brooks interviews Luke Bretherton for Comment.

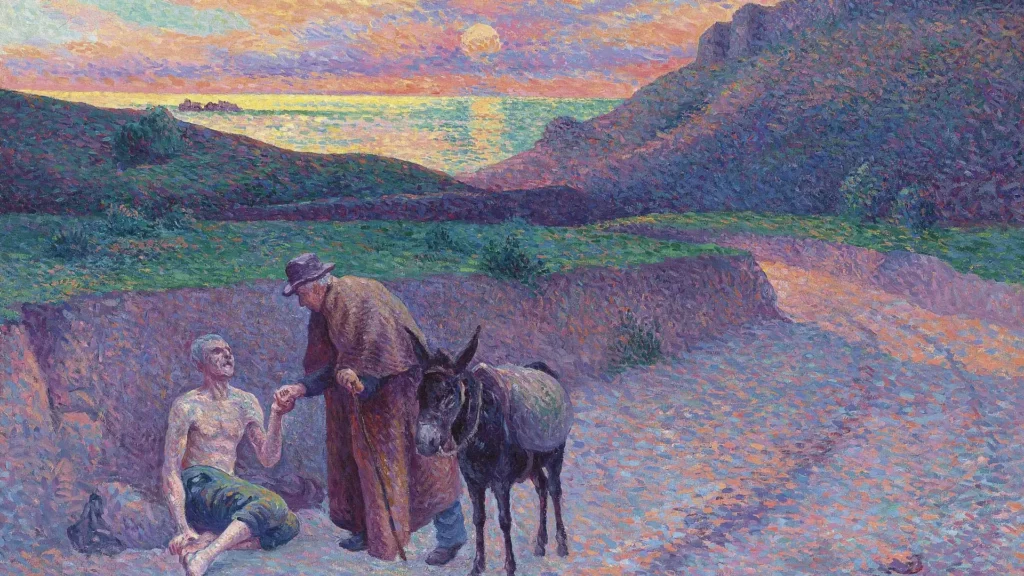

Christian humanists begin with the theological claim that Jesus is fully human as well as fully divine. A scriptural frame for this, one that has been hugely influential in the last two thousand years of artistic production and literature, is the scene in John 19 when Pilate presents Jesus to the crowd and says, Ecce homo: “Here is the human.”

Pilate is preaching against himself, saying, “Here is the true human.” If you really want to know what it means to be human, if you really want to know what it means to live a truly human life, look to Jesus Christ. It is Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection that give us the picture of true humanity to which we can then respond.

So the idea is that even though we’ve lost much of our humanity through sin and idolatry, we can recover it through contemplating Christ. That process of mimesis, of copying, is a way of becoming like Christ, and so becoming truly human again.

“Cormac McCarthy Loves a Good Diner” by Dwight Garner in The New York Times

Cormac McCarthy has long presented himself as a man of simple appetites. When Richard B. Woodward caught up with him in 1992, for a rare profile that ran in The New York Times Magazine, McCarthy was living an austere life in a cottage behind a shopping center in El Paso and eating his meals off a hot plate or in diners.

That sounded about right. Diners — which he sometimes calls cafeterias or lunchcounters or drugstores — are all over the place in McCarthy’s fiction. They’re homes away from home for his drifting men and women.

In a typical scene in Suttree (1979), the eponymous protagonist, mourning the death of his son, enters a bus station cafe alone on Thanksgiving and orders “two scrambled with ham and coffee.” These are served on an “oblong platter of gray crockery” as the cook turns “rashers of brains at the grill.” Now there’s a phrase — “brains at the grill” — that gourmands don’t hear often enough anymore.

“Dancing in the City,” by Elizabeth Bachmann in First Things

I got involved in New York’s swing world this summer, and the “scenesters” I’ve met have been surprisingly varied: elderly couples who have danced together since youth, math teachers, artists, a great many Chinese immigrants, engineers and physicists, a Ukrainian refugee, FANG programmers, political conservatives, socialists, and progressives. The same faces appear on the pier at South Street Seaport for the Danny Lipschitz Quartet on Sunday and Tuesday nights, at Riverside Park on Saturday, at the Gotham Jazz Club on Wednesdays, and at the Frim Fram on Thursdays, beckoned by the siren of swing. And as you dance, you get to talking.

One Comment

Tom King

Top drawer commentary! Great writers, including of course, Mr Brooks, NYT, fine author, Corman McCarthy, and a short, fine quip by author Ms. Bachman, missing only a sentence of two about us octogenarians who danced for years, but now can only clap their hands. Sure miss the dance floor.