by Emily Lehman

In a newly-established routine for a newly-established home, I wander downstairs every morning to sit with the icons.

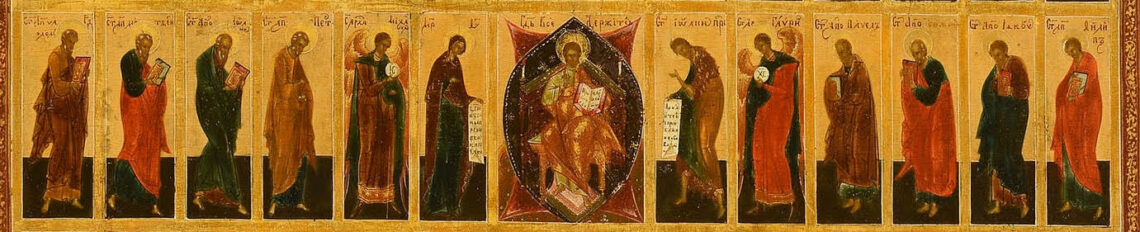

There is a whole crowd of them, perched on windowsills after a failed attempt at wall-hanging, grizzled faces sometimes obscured by the gold background of the next icon, leaning in clusters as if they are keeping one another awake. I often can’t find a match to light a candle in my morning haze, and I sit back against the window seat, not capable of anything but presence.

Some mornings the eyes of the icons are warm, glimmering, sympathetic. I see them looking down at me with the same presence I am trying to bring to them. Sometimes, though, the eyes are hard and judgmental. My mental wiring, developed to track every expression of other humans for my survival, catches every possible sign of displeasure and interprets the hard lines of the faces as set against me. And some days, like today, when the skies are slate-grey and the shades are closed against the nonexistent sunshine, the icons seem lifeless, and my eyes focus on the hard edges of their squared corners.

I try to look into the icons, not at them, and tell myself that the sudden two-dimensionality is a trick of my eyes. But I have learned a hard lesson: one can be very lonely in the presence of icons.

We use the word “icon” in different ways. My new computer also has new icons. Compared to my old computer’s harder edges and more muted colors, these icons are reassuringly childish: candy-colored with rounded, unthreatening edges. Their meanings are simple and straightforward, meant to take me to a web browser or maps, photos or a word processor. Don’t worry, they seem to say. Adulthood can be fun. This won’t be too hard.

The icons downstairs seem to disagree. Saints are often depicted in their icons with a symbol of their life’s work: St. Joseph with his carpenter’s square, St. Matthew with his probably-anachronistic quill pen, St. Peter with his keys. Or a saint is depicted in an iconic scene from his life: Jonah being swallowed by the whale, George trampling the dragon, Lazarus rising from the dead. Or you can identify a saint because they are depicted triumphantly displaying their means of death: St. Lucy with her gouged-out eyes on a tray, St. Sebastian with a handful of arrows, St. Andrew before an X-shaped cross. My patron, St. Catherine of Alexandria, is the epitome of this type, pictured serenely next to the spiked wheel on which the Romans attempted to impale her before the wheel was struck by lightning. In all of these cases, one gets a sense of concentrated life, concentrated personality, that makes the person symbolic. The icon feels like a connection because of this one thread of unique personhood, providing for us a wispy bridge into the afterlife.

We use the adjective “iconic” to describe a person who is so intensely themselves that they leave an indelible impression upon others. But this force of personality is ambiguous. A person becomes an icon for a variety of reasons. Fame, fortune, being preternaturally beautiful, being in the right place at the right time. Die young enough, and you will become an icon, symbolic forever in the minds of those who loved you. In fact, I suspect that this happens when a person dies at all. On gravestones we see these iconic phrases, the verbal version of the symbols and flowers with which the saints are adorned: “devoted mother, loving daughter, caring friend.” The reality was surely complex, but in death it is simple. We become archetypes: mother, friend, sister, daughter. Death seems to be the quickest conversion into symbolism.

Heath Ledger died of a drug overdose after playing the Joker in the Batman movies, and the event quickly became part of the popular consciousness. When we watch Heath Ledger in this or that movie, the remembrance of that mysterious death lingers. Artists often quickly go icon-ward, helped along in some cases by untimely death or suicide. Saintliness seems to be no necessary prerequisite for becoming an icon. Cult leaders, church leaders, musical artists, unhinged personalities, serial killers. We remember their names and their faces; they are iconic. We do not need to love them to acknowledge their indelible depiction in our imagination and their power, power that often redoubles after death when a deceased person’s face greets us from every media outlet the day after their departure. They insist on meaning something to us. And we inescapably respond to that bid for connection, picking up the thread like the threads offered by Jonah and Catherine of Alexandria.

People who like icons are fond of pointing out that one does not “paint” an icon, one “writes” an icon. The writing of one of these glimmering images is a prayer experience, often taking the form of a long religious retreat. I imagine what it might be like to live in this kind of breathy intimacy with a citizen of the heavenly kingdom: spending days upon days tracing the wing of St. Raphael, right up against the irreducible particularity whose meaning is so difficult to tease out. Angels with wings are commonplace—blending into the background of Christmas songs and nighttime prayers. A specific wing, on a specific angel, demands more attention. Did St. Raphael literally have wings? What does that mean? I spend a lot of my time writing words, and wonder whether this connection between writing and icons is indissoluble. Is a word an icon? Is each letter its own small, linear icon? Is everything an icon of itself, or is everything an icon of something else? I do not know.

I used to enjoy reflecting, nostalgically, on the medieval or ancient imagination, where the flock of geese that greeted me on my walk would have been some portent, where liturgy was rich with sign and symbol, where every weather change, crystal, bodily fluid, plant and animal both existed and signified. Something was lost, I used to reflect, in the conversion from a world rich with sacramental meaning to post-Enlightenment empiricism.

But perhaps there never was such a conversion. Everything still means, inescapably. The geese I saw on my walk meant something, I just don’t know what they meant. The leaf I picked up on that walk because its yellow banner was so defiant against the wet grey sidewalk means something, and sits in its mystery on the top of my bookshelf. My modern rootlessness has offered me no respite from the burden of meaning—only more questions. If, as I was once told by a reader of Sartre, absence is also icon, then surely everything is icon. Reality inescapably symbolizes. To one another, we mean things. The things we encounter mean things. My elusive companions downstairs merely teach me something about the whole world—that it is saying something and that I will only sometimes understand.

Sometimes the light goes out of the eyes of your icons and you are left alone to shuffle together meaning in the gathering dark. But I have a suspicion that it is in that darkness that one experiences the flip side of the analogy of being—that while a golden thread connects us to the Infinite, there is overwhelmingly more difference than similarity between us and the source of the meaning we experience. The apophatic, presence-through-absence mode sheds its own kind of light. These icons are not St. Lucy and Jonah and Christ the Good Shepherd—they are images on my wall, and if the house burns down they will burn like other earthly ephemera. We do not live in a meaningless world, but we do live in a world where meaning comes in tiny, perishable threads.

We all need good days with icons—moments where the meaning of life is abundant and overflowing, when the sticky leaves of spring break our hearts with significance. But we also need dark fall days when our icons take a step back and leave us behind, because it is then that we realize that meaning exists outside ourselves. Surrounded by unintelligible symbols, we see our own place in the cosmos: we are not the meaning-makers. Our stories do not provide meaning. They discover it. And the withdrawal of that discovery reminds us that the meaning did not originate in us. No matter my frustrations of interpretation, the icons convince me, by their stubbornness in existing, that reality still means something. There is no iconoclasm.

Emily is a PhD candidate for Theology, the Imagination, and the Arts at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. When not writing about Shakespeare, Dostoevsky and Alasdair MacIntyre, she enjoys long walks, sitting on the floor at parties, cat ownership, and a shameless Taylor Swift obsession.

Header Image: Anonymous Russian icon painter (before 1917), in the public domain. Cropped.