by Anne-Sophie Olsen

Wild Belief: Poets and Prophets in the Wilderness

by Nick Ripatrazone

Broadleaf Books, 2021; 148 pp., $25.99

“Flee, be silent, and pray, for these are the sources of sinlessness.”

This simple refrain, given by the 3rd-century Desert Father Arsenius the Great, distills the wilderness saint’s path to holiness. An echo of Christ’s habit of withdrawing to mountaintops and deserted places to pray, it suggests that, far from being a source of self-absorption or mere asceticism, solitude is a locus for the renewal of spiritual strength and purity.

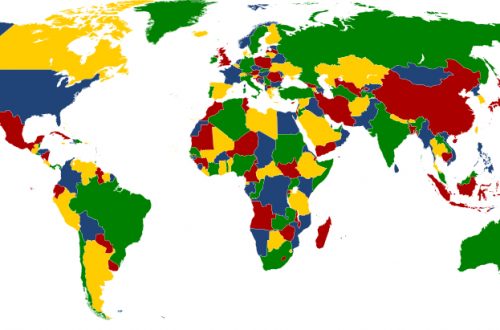

No wonder: civilizations and their religions have long considered nature to be suffused with the divine. From the ancient Greeks, who saw a Zeus in the lightning and a Poseidon in the seas, to the Native American tribes, who thank the spirit of the stag that gives itself up in the hunt — the wild has always been source and sustenance for peoples’ understanding of the divine and their relationship to it. In his newest book, Wild Belief: Poets and Prophets in the Wilderness, Nick Ripatrazone points out that the wilderness is just as essential to the Christian tradition.

In fact, the modern Christian’s lack of connectedness to nature is, Ripatrazone argues, antithetical to the roots of Christianity, which is a Semitic religion “born of sinus-clearing glottal consonants, spit, dust, blinding light.” A Christianity without wilderness is a Christianity stripped of its origins. Ripatrazone goes on to explain: “The further…belief moves from its land of origin, the further it risks being made sentimental, trite, and domesticated. Its roughness and even its strangeness risk becoming neutered in favor of a revised faith born not of desert gales but of gentle breezes that sneak into open windows.”

Wild Belief serves as a literary pilgrimage through the lives of poets and prophets who have allowed the wilderness to transform their lives and their work — who have found the wilderness to be “a locus for renewal,” both spiritually and literarily. As such, the reader who is inclined toward poetry or nature (or poetry and nature) will find this book most immediately engaging. But those interested in Christianity’s roots in wilderness tradition will also be enlightened, not merely to the sources of Christianity but also to the contemporary vitality of those sources. I have heard the Great Books described as “great, not because they are old, but because they are living.” The same could be said for Christianity’s wilderness tradition, which Ripatrazone proves is very much alive in the work of poets and prophets both ancient and new.

~~~~~

Wild Belief begins with the wilderness tradition’s appearances in Sacred Scripture. In Ripatrazone’s words, the Bible “teems with wild places where faith is tested and reborn.” It is a place “of suffering, [but] also a place of renewal. From [it], the voice of John the Baptist called out, and there, Jesus would retreat to pray—and would also be tempted.”

As a physical space, a wilderness is a borderland, a territory that civilization has not claimed and tamed. Consider treacherous marshlands and heat-ravaged deserts. Consider, too, how these borderlands make their way into the literary imagination: the haunted wetlands of Tolkien’s Dead Marshes, through which Frodo and Sam must be led by Gollum on their quest to Mount Doom, or the dark forest into which Dante wakes at the opening of the Inferno, a symbol for the darkness of sin from which Dante must be led by Virgil toward the light of the beatific vision. For both Tolkien and Dante, the wilderness is a trial and testing ground.

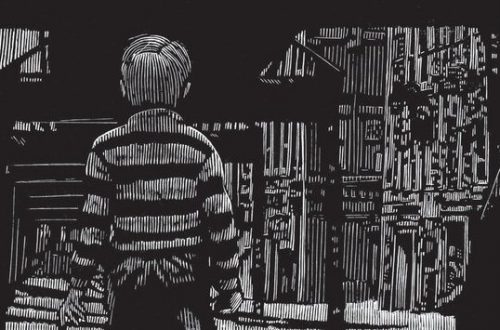

So it was as well for the Desert Fathers, who allowed the wilderness to test their bodies and wills in order that it might purify their souls. Quoting the philosopher-monk Thomas Merton, Ripatrazone notes that “the law of the desert was the law of the Sabbath, of peace, direct dependence on the Lord, silence and trust, forgiveness of debts, restoration of unity, purity of worship.” The physical wilderness was the Desert Fathers’ hard path to a grace-filled life.

~~~~~

Wendell Berry, who is one of the contemporary poets Ripatrazone writes of in Wild Belief, wrote this poem, called “The Peace of Wild Things”:

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

The stillness and simplicity of the poem’s final line, which is both summit of and response to the restlessness that precedes it, beautifully enacts the transformative capacity of the wilderness. The troubled poet journeys into the wild and through it is briefly released into peace.

Given in the language of grace and freedom, the poem seems like an echo of Merton’s desert peace, the peace which is the “law of the Sabbath.” As such, the poem itself offers the reader the opportunity to take the poet’s journey into spiritual awareness, albeit through language and the imagination rather than literal travel. Though I have not seen the wood drake rest “in his beauty on the water” or been sensible to those “day-blind stars / waiting in their light,” Berry’s language lures me into stillness and serenity. This is a spiritual grace in a distracted and fragmented world, if I am willing.

In Ripatrazone’s words: “Great writers of the wild can help us better see so that we might go back to those spaces with a closer sense of texture.” Indeed, this is what Berry’s poem does for me, reigniting a desire to seek out and submit to a divine wildness that is present nowhere else in my life but in nature.

The poem also illustrates what Ripatrazone sets out to do, and what he accomplishes so successfully, in Wild Belief. That is, he reveals, through the lives of poets and prophets, how the wilderness directly transforms them, and how studying the works of these individuals consequently transforms us. As the wilderness leads prophets and poets into deeper communion with the divine, their works can lead us back to the wilderness with a renewed sense of its divine vitality.

Anne-Sophie Olsen hails from St. Paul, MN and is currently pursuing her MFA in Roanoke, VA, where she lives in a barn with a cat named Pip. Her work has also appeared in Birdcoat Quarterly.

Header Image: “Prayers in the Desert,” William James Müller (1812-1845), Birmingham Museums Trust (public domain)