by Abbey von Gohren

It seemed like an unlikely place for a revelation, but I’m probably being too snobbish. We entered the Mall on a quiet, sunny afternoon after parking on the Arizona level, the one with the cactus and the green border. Finally, after striding through Nordstrom and the nostalgic smell of Cinnabon mixed with Bath and Body Works, we arrived. In the flesh. The visit began with a dance around a string of dots on the floor promoting “social distancing,” those ubiquitous circles which have become a daily reminder of my love of mild rebellion, as I choose whether to follow their injunction perfectly, partially, or not at all. Or obey but act nonchalantly, as if my feet accidentally find their proper place in the moral order. Lord have mercy.

As I was saying, we were at the Mall (first time in a year…years?) expressly seeking an encounter with beauty. High-quality digital reproductions of the Sistine Chapel were on offer in the form of a traveling exhibit for the outing-starved Americans who certainly wouldn’t be boarding a plane to Rome anytime soon. The famous Sibyls, prophets, Adams and Eves, Jonahs, and Christs could now be studied up close, “as the artist would have seen it” atop his scaffolding. An intriguing proposition, at the very least. I thought, reflexively, is it worth the risk of going in person? and decided that yes it was.

I noticed the beauty of crinkly eyes of extended family members first, smiling above masks, as we waited in the cavernous space which sucked air in and out, breathing for us. A group of vulnerable mouths, lungs, bodies…all together on a bet that this was worth it. Yes. You and I both brought ourselves here, incarnate, if you will. I thanked my mother-in-law for getting us out of the house, but there was more to my gratitude. Thank you for giving us bodies again, I silently thought. After a year of dislocated heads on Zoom, thank you for this.

Since I had arrived with a 5-month-old strapped to my chest and a 5-year-old attached to my hand, I was constrained by their needs, their timing. In addition, I am not exactly feeling svelte and deft in my own bodily movements postpartum, either. Our visit was slow, halted, and far from the people I supposedly came to spend time with, but no matter. (All bets are off in a museum— each man for himself. That’s a family rule!) I questioned my small son about what he saw as he walked around with the audio guide trailing from his ear. I pondered within. Why was the Sibyl dressed like a rainbow? Why was Jonah’s fish so small? How is Noah’s drunkenness and getting exposed to his sons related to Christ’s incarnation? That last one really stymied me. I could follow the logic of the flood and Christ’s baptism and the post-flood sacrifice and the cross, but that embarrassing wine incident? That whole thing was an unseemly event which I struggled to explain in any coherent way to my son, or even myself. His body is seen by….wait, how does it go?

Then Noah began farming and planted a vineyard. He drank some of the wine and became drunk, and uncovered himself inside his tent; Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brothers outside. But Shem and Japheth took a garment and laid it on both their shoulders and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were turned away, so that they did not see their father’s nakedness. When Noah awoke from his wine, he knew what his youngest son had done to him. So he said: “Cursed be Canaan; A servant of servants, He shall be to his brothers” (Genesis 9:20-24).

It’s a strange story to begin with, and now it was being equated in the exhibit’s literature to a foreshadowing of Christ’s coming in the flesh. A naked man, pitiful and shameful. Two sons turn away their gaze, while one looks on, and is cursed for it. In Michaelangelo’s painting, Noah and Ham are in light while the other two sons are in shadow. What could this all possibly mean, especially in light of Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection, which we’d just come from celebrating?

The more I thought about it, I realized that a good many scenes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel are preoccupied with bodies and nakedness, shame and glory. In fact, the exhibit wraps up with the Last Judgment, where bodies are on display in every possible state–rising from skeletal remains, clinging to life, contorting in pain, enraptured, and mostly unclothed. Mostly. Some, such as St. Catherine and St. Blaise, are wearing garments. These stand out. And, as you may have learned from your high school art class or a trip down a Google rabbit-hole some late night, this is only because a year after the great artist’s death, some of the nudes in more “controversial” positions were duly draped by a nervous Renaissance version of Shem and Japeth, a painter known thereafter as the “breeches maker,” Daniele da Volterra.

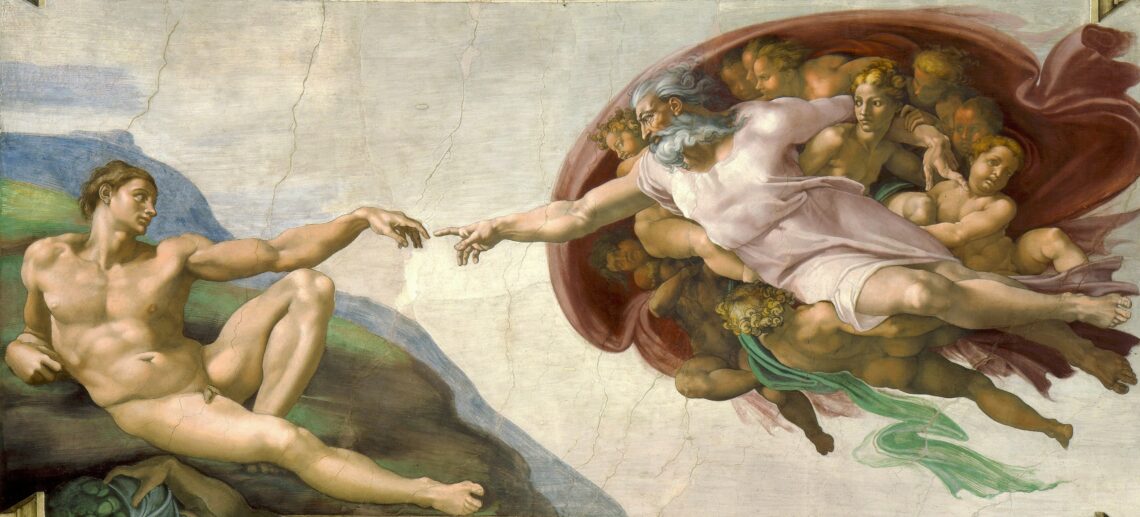

Still, only a handful of them are actually covered. The Council of Trent was a bit half-hearted, at least in this area. And you can still glimpse the original, thanks to a copy a contemporary artist made before the, er, adjustments. As I continued studying the Last Judgment wall, though, I began to notice something else that was odd about the figures. All of the bodies were grotesquely, impossibly muscular. Christ’s torso looks like several torsos compacted together, St. Catherine (seen above) appears like a bodybuilder despite her hurried afterthought of a dress, and St. Peter could be a bouncer in a famous club. (Come to think of it, maybe he is…) At first, I chalked these anomalous proportions up to the fact that this was a sculptor doing frescoes, having a love for curves. Yes and no. Michaelangelo’s extraordinary genius for translating his sculpture work into paintings surely comes out in the paintings from the ceiling, as with the celebrated Adam here:

But there’s something different happening on the Last Judgment wall, which (as I discovered) was painted 1536-1541, about 30 years later, post Reformation and Sack of Rome. Major events in civic and religious life had shaken the city to its core, and some art historians think that the move from the gorgeously painted ideals above to the ungainly bodies on the altar wall may have had something to do with these reckonings.

Regardless, what is the deal with all of this body upon body (over 300 of them), so heavy that some of the saints need to be pulled up to heaven by the scruff of their necks or their rosary beads? Body is not sin, because Christ has one. (Even if it does look a little out-of-proportion, like the barrel-chested body of an Ares with the elegant head of an Apollo!) But the body is heavy, holds us down. This is not just a middle-aged Michelangelo with a few extra pounds from sitting around — he attributes more body to everyone, saints and sinners alike. (In fact, famously, his self-portrait is actually embedded in the flayed skin held by the saint to the left and below Christ.)

I thought back to my decision to even go on this outing. I had wondered whether it was worth the risk of infection, coming in person. Why not just pull up the images online? I was already one step removed, since these were digital reproductions, after all. But it seemed so essential somehow to actually come. And this is why. Bodies. C.S. Lewis said somewhere that the oldest joke in the universe is that we have bodies, and I do laugh at mine as well as cry about it. Christ came, died, rose, and will come again in one.

So, human, rejoice that you have a body. It may be prone to illness, easily tempted, heavy and awkward in social situations, and marked with wounds and pain. But so is our Lord’s. And we will yet rise with him, naked to reveal every scar, our shame now remade into glory.

No need for a breeches-maker here.

Abbey von Gohren is from Minneapolis, MN. She teaches French and leads high-school seminars on philosophy, history and literature. Otherwise, she spends her time playing with Legos, assembling words into poems, exploring the great wilds of Minnesota, and listening to music made by loved ones.

Header Image: “The Creation of Adam,” Michelangelo, 1512 (public domain)

10 Comments

Diane

Oh, dear Abbey! What a lovely, thoughtful meditation. Thank you.

Beatrice Dick

Lovely Abbey.

I kept thinking, however, that you would get around to talking about the distortions necessary for viewing images painted on curved surfaces from a distance. That has always fascinated me. Maybe that is irrelevant to your musings. I suppose you saw everything close up? I do agree with your perplexity about Noah’s drunkenness forseeing Christ’s incarnation.

I also identify with your mixed fear and joy at getting out again! Would love to see you.

Abbey

That’s so interesting, Beatrice, about the necessary distortions. The odd part is, the curved areas were the ones which looked relatively “normal” in body mass, while the last judgment wall (which is mostly flat, I am presuming here…) was where the distortions were present. Now I must look into this, though!

Would love to see you and introduce you so our boys.

Hee-Jung Nicka

A insightful reflection, Abby! Thanks for sharing this link with me.

Hee-Jung Nicka

Oops typo-“An insightful reflection” 🙂

Tom King

Abbey, I am counting on that final miracle that one day restores my mess of errant cells of the current me into what’s called, I’m told, the Glorified me. Amen.

Abbey

Amen, brother.

Robbie Lewis

Love how these musings take my mind wandering down its own turning paths! Thank you for that.

Henry Lewis

Just lovely. You take a simple outing and open the window to heaven. It is like standing in the sunshine. Thank you.

Alan Lewis

Ya these bodies… hard to live with them… can’t live here without them. I especially like getting old. It’s hard but rich. God’s perfect pleasures to us here.

Alan