by Timothy Dusenbury

Comparison is the thief of joy. — Teddy Roosevelt

Humility is endless. — T.S. Eliot

I want to be famous / so I can be humble / about being famous — David Budbill

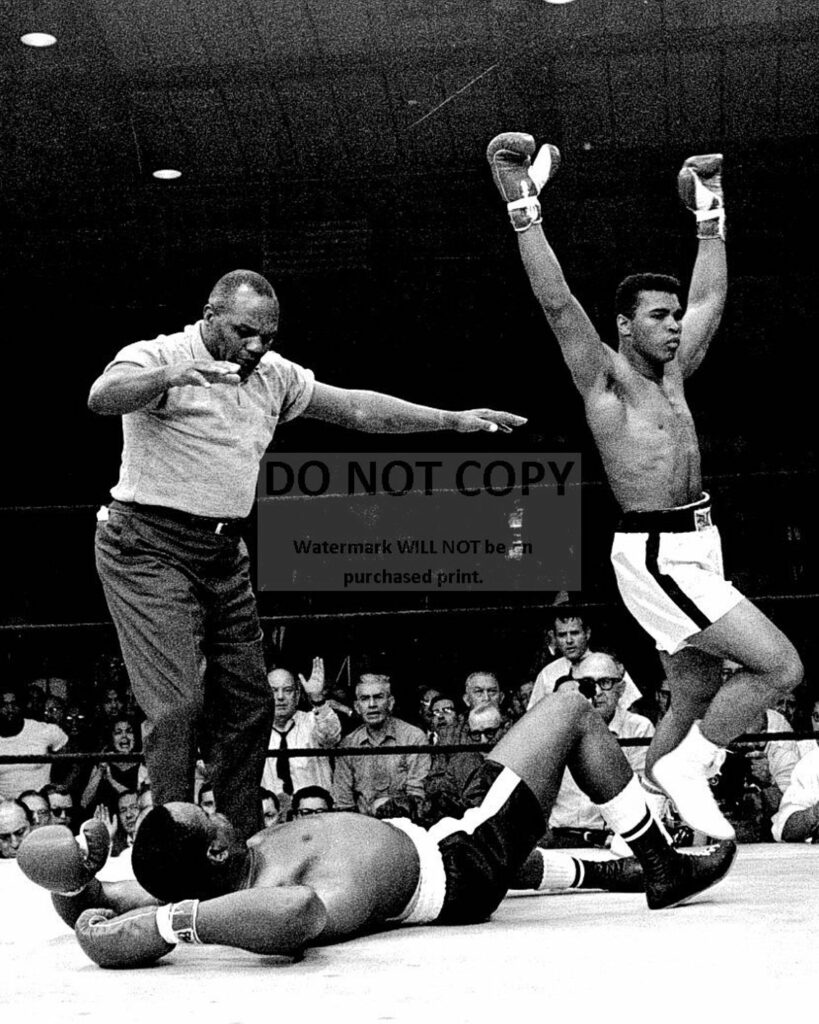

When I was eight, I saw a photo of Muhammad Ali delivering the knockout to Sonny Liston. I was awestruck. The next Saturday, when I was lucky enough to win my little league wrestling match, I tried to replicate Ali’s pose. My parents called me up to the bleachers and I received an early lesson in humility, or at least in modesty. Act humble.

This piqued my curiosity, and I began listening for clues in sermons and books. Humility, I came to think, meant finding a way to think badly of yourself. Saints seemed to think they were really terrible people. I tried this for years, with some success, but it was difficult. I didn’t want to be a worm, and when I knew I was one, I preferred to look elsewhere. Besides, there were some things I was good at: I could spell; I could run pretty fast.

In my twenties I began hearing that humility was not self-loathing, but rather genuine self-knowledge, “a sort of supernatural common sense,” as Thomas Merton says. This helped. But a watershed came when I happened upon Martin Buber’s Hasidism and Modern Man.

“God never does the same thing twice,” said Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav. This applies to natural phenomena like blades of grass and the veins on leaves, but is also true of every human. According to Hasidic belief, each person is utterly unique, unrepeated and unrepeatable. This singularity gives them a foothold in eternity, “for had there ever been someone like them, then they would not have needed to exist.”

And because of this, everyone must discover their own unique manner of service, there is no one or general way to serve God.

“For one way to serve God is through learning, another through prayer, another through fasting, still another through eating . . . What sort of God would that be who has only one way in which he can be served!” taught the “Seer” of Lublin.

How does humility come into this? In a cosmos where “each soul stands . . . in the majesty of its particular existence,” comparison is meaningless. People are apples and oranges. The urge to compare ourselves stems from a desire to surpass. “The haughty man is not he who knows himself, but he who compares himself with others.”

Does that mean that the whole Muhammad Ali vs. Sonny Liston thing is a mistake? Maybe. Certainly if the competition is existential.

Instead what is called for is love and reverence for every human person. Buber quotes Pinchas of Koretz: “In everyone there is something precious that is in no one else. That is why it is said: Despise not any man.’”

This take on humility came as a great relief to me, grounded not in my own limitations and sin, but in God’s goodness in creation. Still, the question remains. How do you make it to ‘being humble’?

Part of the answer is, You don’t.

Self-conscious struggle, “self-humbling, self-restraining, self-resolve,” is counter to the nature of humility. “If anyone were humble in order to keep a commandment, he would never attain it.”

The goal instead is a childlike self-forgetfulness.

Buber tells the story of Rabbi Hayyim of Zam, who complained that he had not yet atoned, his friend replied, “How about forgetting yourself and thinking of the world?”

The rabbis agree that “we will struggle with pride all our lives.” The fact that humility is unattainable might actually be liberating.

Personal comparison is a false search for primacy and self-sufficiency. It isn’t a question of Ali or Liston. We are not intended to compete but to serve and be filled; to play our singular part in revealing and freeing the glory of God in all creation.

At the end of his life, Rabbi Susya told his disciples, “In the world to come they will not ask me: ‘Why were you not Moses?’ instead they will ask: ‘Why were you not Susya?’”

Timothy Dusenbury lives in northern Virginia with his wife and two young sons. He teaches high school, plays organ, and attempts woodworking projects. You can find his music at timothydusenbury.bandcamp.com. His poem, “To the Light on the Floor” was also recently published by Veritas Journal.

Header Image: Exterior of the Baal Shem Tov’s Shul in Medzhybizh, c. 1915 (public domain)