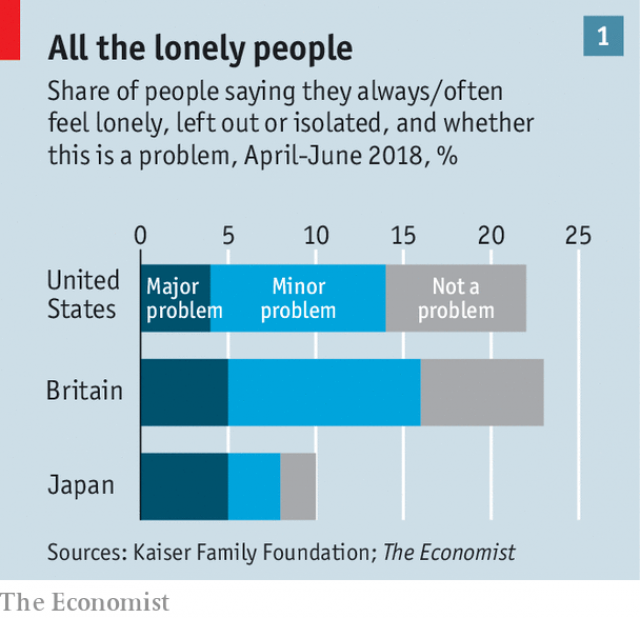

“All the Lonely People,” in The Economist

Doctors and policymakers in the rich world are increasingly worried about loneliness. Campaigns to reduce it have been launched in Britain, Denmark and Australia. In Japan the government has surveyed hikikomori, or “people who shut themselves in their homes”. Last year Vivek Murthy, a former surgeon-general of the United States, called loneliness an epidemic, likening its impact on health to obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes per day. In January Theresa May, the British prime minister, appointed a minister for loneliness.

That the problem exists is obvious; its nature and extent are not.

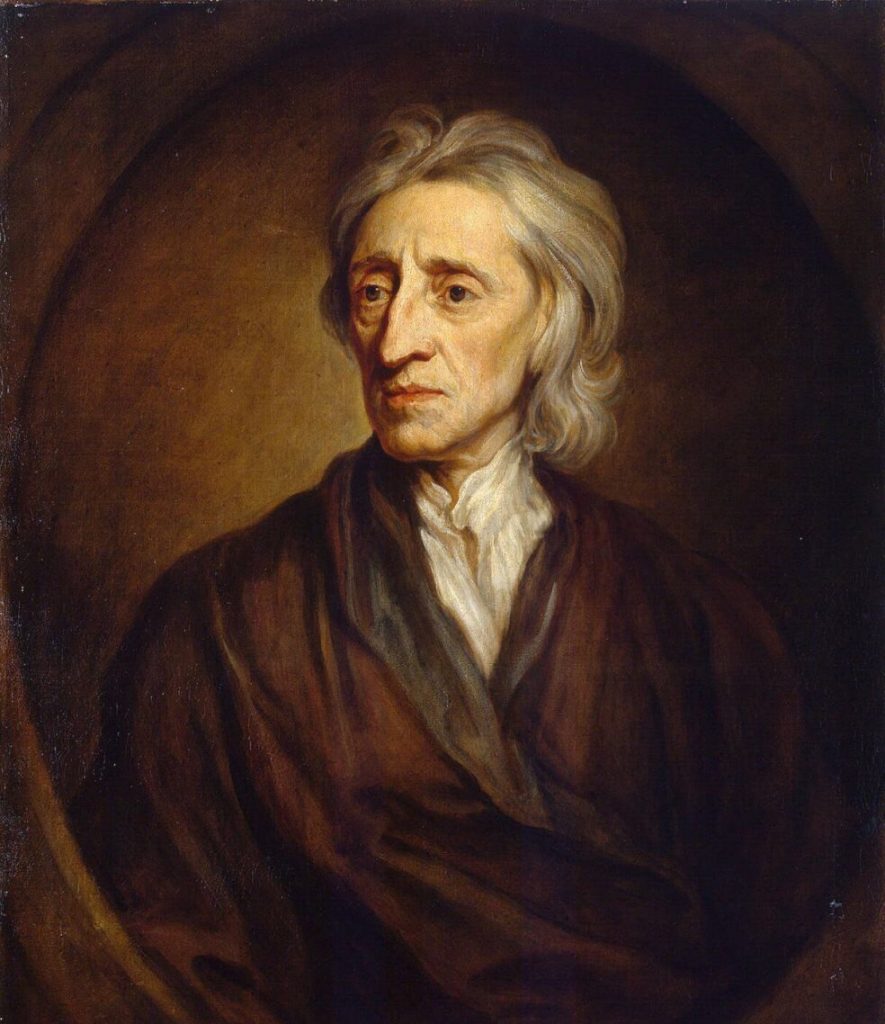

“Unkown Text by John Locke Reveals Roots of ‘Foundational Democratic Ideals’,” as reported in The Guardian

A “once in a generation” discovery of a centuries-old manuscript by John Locke shows the great English philosopher making his earliest arguments for religious toleration, with the scholar who unearthed it calling the document “the origin and catalyst for momentous and foundational ideas of western liberal democracy”.

“Three Decades Ago, America Lost its Religion. Why?” by Derek Thomas in The Atlantic

Although belief in God is no panacea for these problems, religion is more than a theism. It is a bundle: a theory of the world, a community, a social identity, a means of finding peace and purpose, and a weekly routine. Those, like me, who have largely rejected this package deal, often find themselves shopping à la carte for meaning, community, and routine to fill a faith-shaped void. Their politics is a religion. Their work is a religion. Their spin class is a church. And not looking at their phone for several consecutive hours is a Sabbath.

American nones may well build successful secular systems of belief, purpose, and community. But imagine what a devout believer might think: Millions of Americans have abandoned religion, only to re-create it everywhere they look.

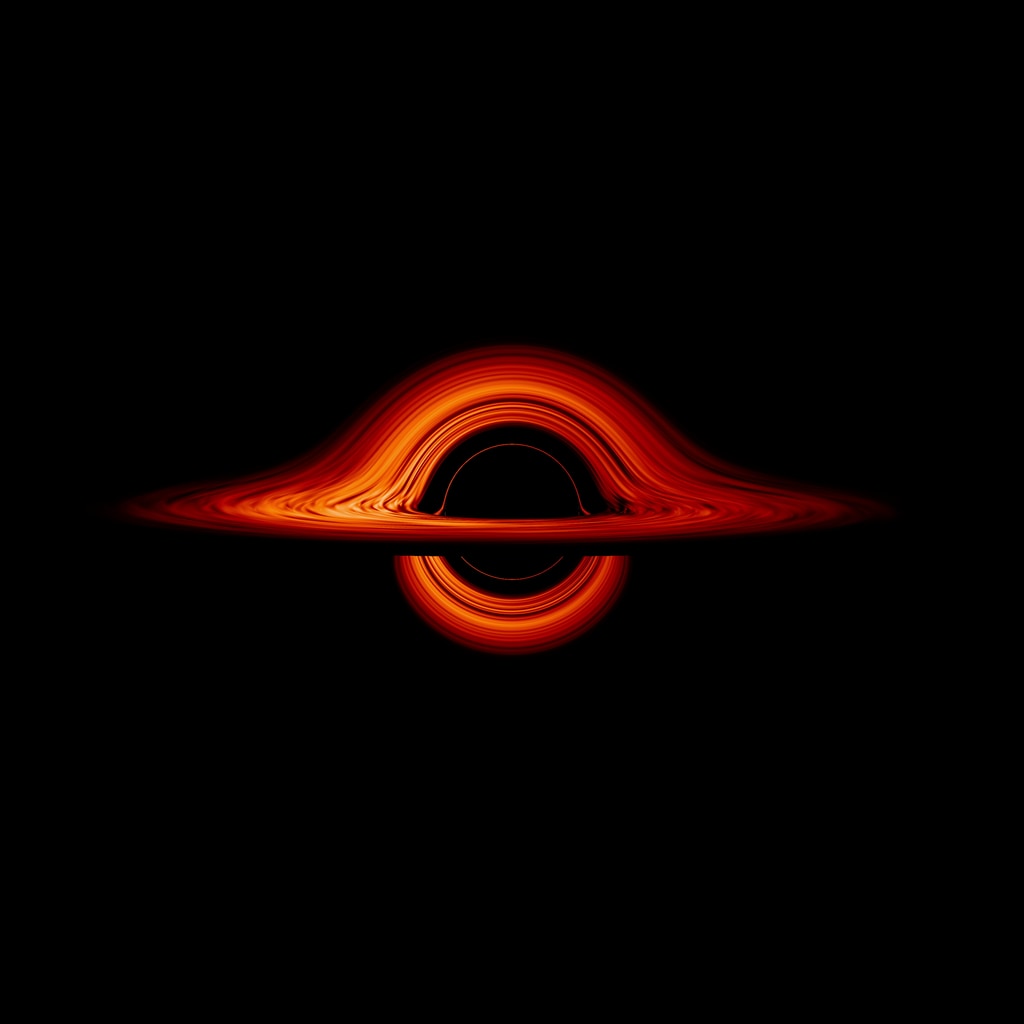

“A Different Kind of Theory of Everything,” by Natalie Wolchover in The New Yorker.

In 1964, during a lecture at Cornell University, the physicist Richard Feynman articulated a profound mystery about the physical world. He told his listeners to imagine two objects, each gravitationally attracted to the other. How, he asked, should we predict their movements? Feynman identified three approaches, each invoking a different belief about the world. The first approach used Newton’s law of gravity, according to which the objects exert a pull on each other. The second imagined a gravitational field extending through space, which the objects distort. The third applied the principle of least action, which holds that each object moves by following the path that takes the least energy in the least time. All three approaches produced the same, correct prediction. They were three equally useful descriptions of how gravity works.

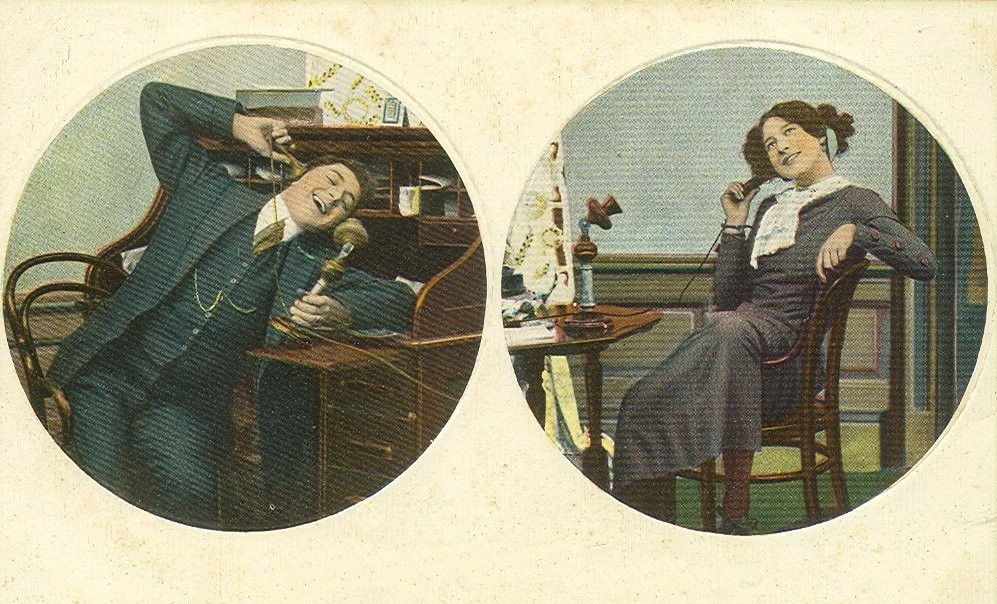

“Talk to People on the Telephone,” by Amanda Mull for the Atlantic

Chatting on the phone provides the bliss of unreviewable, unforwardable, unsearchable speech. If something comes out a little weird, there’s no record of it (unless your conversation partner is secretly recording it, in which case you have deeper problems). If you misunderstand something, there’s no day-long email chain correcting your error. If a conversation has a tense moment, you can’t scroll back up to critique your performance until the heat death of the universe. Snapchat blew up a few years ago because pictures sent between users on the app disappeared 10 seconds after being viewed; talking to someone on the phone has provided the same freedom in verbal form since the days of Alexander Graham Bell.

What has awakened your wonder in the past few weeks? Share it in the comments below!

One Comment

Matt Axvig

Regarding the “loss of religion” article linked to here, this quote from it reminded me of something:

“Although belief in God is no panacea for these problems, religion is more than a theism. It is a bundle: a theory of the world, a community, a social identity, a means of finding peace and purpose, and a weekly routine. Those, like me, who have largely rejected this package deal, often find themselves shopping à la carte for meaning, community, and routine to fill a faith-shaped void. Their politics is a religion. Their work is a religion. Their spin class is a church. And not looking at their phone for several consecutive hours is a Sabbath.

This idea of a “bundle” working to provide meaning to life reminded me of a video of Charles Taylor, author of “A Secular Age”, who also speaks of “bundling”. He also speaks to how the church can work in and with a secular age where things are “un-bundling”.

Here’s the link to the video:

https://youtu.be/152Ng0qYRIM