by Jon Balsbaugh

Longtime educational crusader Alfie Kohn recently penned a compelling opinion piece for the New York Times on the dangers of traditional grades and their use by the educational establishment. The basic message of Mr. Kohn’s piece is right on. He writes:

The goal … isn’t to do well but to defeat other people who are also trying to do well. Grades in this view should be used to announce who’s beating whom. And if the students in question have already been sorted by the admissions process, well, they ought to be sorted again. A school’s ultimate mission, apparently, is not to help everyone learn but to rig the game so that there will always be losers.

Psychologists have long known that external rewards and punishments decrease intrinsic motivation. Yet, our educational system presses on, largely fueled by them. Genuine learning is one of the most pleasurable of human activities. It provides students with authentic knowledge about themselves and the world in which they live, as well as skills that will serve them throughout their lives. However, we continue to send students the message that if and only if they achieve measurable results in the form of a high GPA and stellar SAT or ACT scores will they reap the real rewards of education: entry into the college of their choice, access to economic prosperity, and assurance of financial security. We talk about the joy of learning, but burden students with grade consciousness, high-stakes testing, anxiety about the future, and pressure to succeed in the narrow, competitive terms of the college admissions game. In this respect, Mr. Kohn’s critiques are certainly on the right track.

But there was one element left out of consideration in his democratic assessment: the very undemocratic nature of excellence and its role in the education of a human being. Yes, grades are an ephemeral measuring stick created by a technological age, but the recognition of excellence is as old as culture itself and plays an important role in our lives.

During the summer Olympics in 2016, I became enamored of elite-level archery. Though I owned several bows when I was young, I had never really paid any attention to archery in the Olympics. But this time I was blown away by the command of these archers. The performance of the teams from South Korea was particularly astonishing. No one else even came close to their poise and consistency. It was simply amazing! The men won the team gold medal match 6-0, the women won the gold medal 5-1, Ku Bon-chan won the men’s individual gold 7-3 and his compatriot on the women’s side, Chang Hye-jin, also dominated her gold medal match 6-2.

The effect upon me was immediate. I wanted to go get a bow again, stand a hay bale up in my back yard, and practice until I could steady myself enough to make just one of the shots they were making time after time.

This instinct to pick up an activity for yourself after seeing something like an Olympic competition is powerful, but it is also strange. Let’s be honest, whatever that instinct of mine was, it was not about making the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. The obstacles are too many and too significant. I don’t possess the necessary genetic gifts. Furthermore, it is far too late for me to start the kind of training that Olympic excellence requires. And (truth be told) I probably don’t have the competitive drive that is essential for such success.

Still … even thinking about those archers three years later makes me want to pick up a bow. I would love to make an arrow sail through the air and hit the target dead center. I think I find myself wanting to pick up a bow because what those archers are able to do is excellent. Excellence is the point at which the performance of a skill becomes beautiful. And beauty calls forth imitation.

The beauty of excellence provides us not only a vision of greatness but also a vision for greatness: greatness in a particular skill, greatness of the human spirit, greatness of human achievement, and greatness in our own lives. It doesn’t matter that I will never be an Olympic champion, let alone wield a bow with the mastery displayed by those Korean archers. But to wield the bow even well enough, to competently perform a skill that is capable of producing beauty … even that would be something worth doing.

This is the real value of excellence: that it inspires its own pursuit.

So what if, rather than focusing on grades and test scores, we could inspire students to think about academic excellence the same way in which we experience excellence in an Olympic sport or other activity? What if students were encouraged to pursue excellence in some academic exercise the same way they might pursue archery after seeing it practiced in the Olympics – for the love of the activity, for the beauty that comes from skillful execution, and for the desire to participate in a thing done well?

In order to do so, we would have to change the way we thought about excellence in academics. First of all, excellence would have to be disassociated from grades or awards. To say “The Korean archery team is excellent at archery” does not mean the same thing as to say “The Korean archery team won a gold medal.” The Korean archery team could have stayed home and still been excellent at archery. The excellence of the archer is in the shot, not on the medal stand. So the excellence of a student’s work should not be in the final ‘grade,’ but in a watercolor wash skillfully performed, a mathematics problem elegantly solved, or a paper insightfully written.

Secondly, we would need to be honest about the fact that academic excellence is in many ways not much different from excellence in an Olympic sport. There is a natural component to doing excellent work in mathematics, for instance, that has no less of a biological basis than Usain Bolt’s athleticism. Pattern recognition, the speed of identifying and processing relationships between symbols, the capacity for intuitive leaps, an element of natural risk-taking … these are all required to produce truly excellent mathematics, and they all have at least some neurochemical basis. This is a tough reality. Just as not all student-athletes are able to break school records in track, shoot three pointers under pressure in a game, or place in the state wrestling tournament, so not all students are able to produce truly excellent work on a continual basis in everything they are asked to do. But in my experience, young people can handle this reality. They can certainly handle it better than being told that if they only worked harder, put in more time, focused, got extra help, and so on, they too could earn that A+.

Finally, if we were to transform the nature of academic motivation, we would need to make sure students understand that excellence is worth pursuing no matter what. It is a mistake for students to think that just because their work is not as skillfully done as another’s, there are not elements of excellence in it. And it is a mistake for them to think that just because they can’t do something excellently on a consistent basis they shouldn’t do it at all.

Our children are hungry for beauty, meaning, and something worthwhile to strive for. It is a tragedy that our educational system is failing to consistently provide these things. Mr. Kohn is right that a hyper-competitive environment driven by grades is a large part of our current problem; but if we were to succeed at least in putting grades and test scores back in their proper place the motivational void left behind would need to be filled.

Norman Maclean writes in A River Runs Through It (a novel as much about the beauty of excellence as it is about fly fishing): “One of life’s quiet excitements is to stand somewhat apart from yourself and watch yourself softly becoming the author of something beautiful even if it is only a floating ash.”

As parents, educators, and citizens, we should work to transform our culture of education so that grades and high stakes testing no longer fuel dangerous competitive anxiety. Rather, we should work to establish a culture in which education is driven most deeply by each student’s own sense of watching himself or herself softly becoming the author of something beautiful.

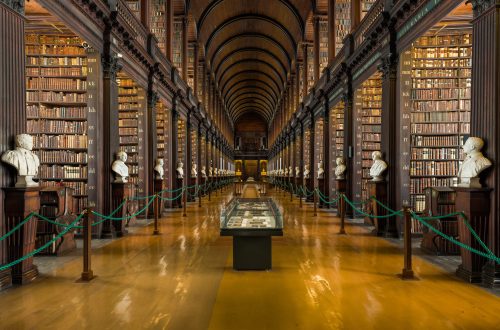

Photo courtesy of Korea.net via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons 2.0.

Jon Balsbaugh is the founder and chief editor of Veritas Journal and owner and operator of Kairos Educational Consulting. Though his soul still imagines itself in the Pacific Northwest of his childhood, he now lives in South Bend, IN. He and his wife have five children. Mr. Balsbaugh has been involved in classical education for over twenty-five years. In addition to reading, writing, and thoughtful contemplation of ideas, he enjoys seeing the world through the lens of his three primary hobbies: fly fishing, foraging, and photography.

.

2 Comments

Paul Go

Hi Jon,

What an excellent article. I especially enjoyed this sentence:

“Genuine learning is one of the most pleasurable of human activities. It provides students with authentic knowledge about themselves and the world in which they live, as well as skills that will serve them throughout their lives. ”

It explain why I keep taking classes at ND. Because it is pleasurable. I think that is what Eric Liddell in “Chariots of Fire” said when asked by his sister why he runs. It gives him pleasure.

Paul

Jon Balsbaugh

I am so glad that you are still enjoying learning so much, Paul! Thanks for the comment.