by Elsa Lagerquist

As an artist, the textile world captivates me. Fabric is beautiful to look at, but it demands to be experienced not just by looking, but by touching. That is what truly excites me. It was three years ago when I discovered this passion in the dye lab at the Rhode Island School of Design. Over the course of six weeks I spent hours upon hours in the lab learning how to dye fabric. I felt free, messy, creative, and productive. Using my slightly stained and colorful hands to scrunch and fold and stir and dry and iron till I had yards of transformed cloth, I finally felt like something of an artist. And it was during that summer that I was exposed to Japanese shibori dyeing.

Even if you don’t know it by name, you have probably seen shibori-inspired creations before. The blue and white ‘watercolor-esque’ patterns have started to appear on everything from throw pillows to summer dresses. Shibori is trendy now, but it is an ancient art.

Shibori is one example of a process known as resist-dyeing, a traditional method of creating patterns with dye by somehow preventing dye from permeating the entire piece of fabric. When completed, a pattern in the color of the original fabric emerges against the background dye color itself.

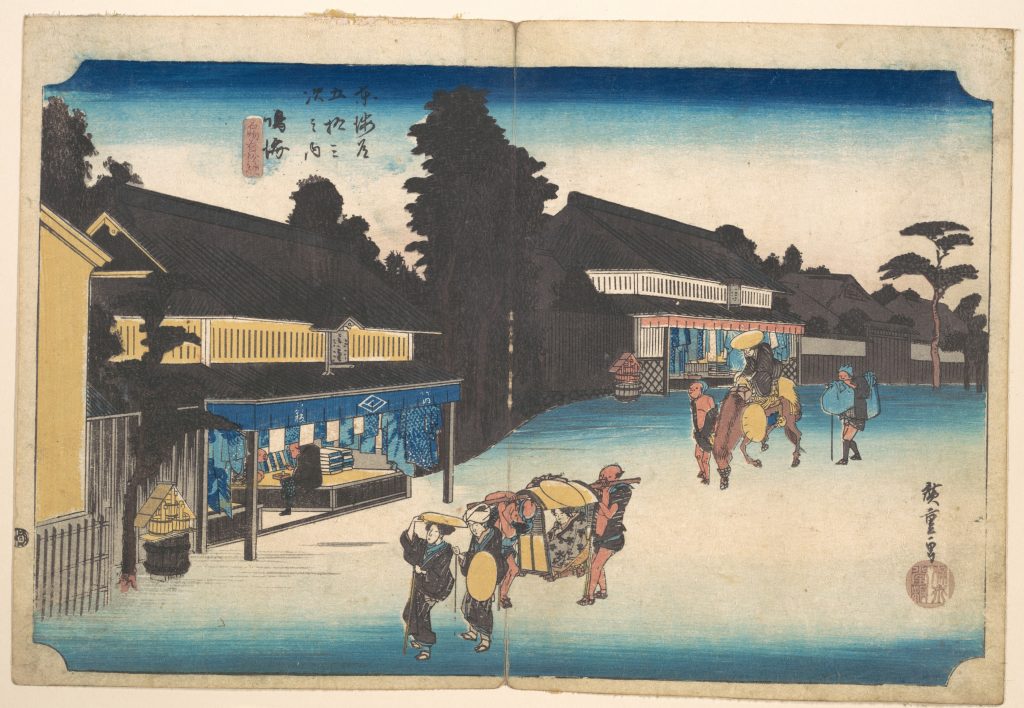

The earliest existing examples of such fabric in Japan date back to 756 A.D. But possible references to resist-dyed cloth, some from other parts of Asia, appear in historical accounts from hundreds of years earlier. Some Japanese block prints actually depict different parts of the shibori process. In this print from the 1700s, you can see the blue fabrics hanging from the ceilings of the studios. (The blue of the cloth comes from indigo, one of the oldest and most significant natural dyes.) The pieces of cloth are even detailed with splashes and dots of various shades, suggesting the effects of resist-dyeing.

Unfortunately, the precise description and meaning of shibori gets lost in translation. What we know as tie-dye, for instance, looks like this Asian art and uses some of the same principles, but it is something of a degradation to put them in the same category. Shibori techniques go far beyond the use of simple rubber bands, and the complexity of the designs can be astounding. In Stitched Shibori, Jane Callendar writes:

“Crisp knife-edge folds in cotton, silks that float on a breath, the chameleon nature of man-made fibres; the unique characteristics of cloth are revealed through the manipulations of shibori. But how to properly define the process? The Japanese term shibori comes from the verb ‘shiboru,’ meaning to wring, squeeze or press. It could be interpreted as ‘compressed’ or ‘pressurized’ – a clumsy description might be that ‘fabric is compressed to block the dye.”

To begin, the cloth is stitched, bound, and twisted to create the desired design. Using rubber bands, wood blocks, clamps, beads, and thread, you can create an infinite number of patterns and shapes. The Japanese shibori tradition recognizes six distinct techniques: kanoko, miura, kumo, nui, arashi, and itajime shibori. Itajime is one of the more simple and quick methods as it requires folding the cloth and sandwiching it tightly between pieces of wood. Tie-dye is most related to kanoko, which involves pinching particular areas, especially to create circular patterns. My personal favorite is nui shibori. This technique is about creating designs by stitching and gathering, and it can feel like a bottomless pit of options. The final result depends on the spacing and length of the stitches and on whether or not the cloth is folded. It is possible to create any shape by stitching its outline and gathering.

Below is the progression of a stitched diamond design, which would fall into the nui and kumo categories as it involves stitching and binding with thread:

First, the diamond shapes are created on a fold. Then, the thread is gathered and wrapped around the fabric to “fill in” the shape more. The key is gathering the stitches or binding the fabric tightly enough so that the dye cannot get in. But water seems to have a mind of its own, so mastery is difficult and flexibility is required. The artist must understand how the water will most likely respond to the guidance given (in this case by thread, wood, and other materials), but must also be ready for a bit of a surprise at the end. The World Shibori Network website describes the charm and risks of this art: “The Japanese shibori dyer works in concert with the material, not in an effort to overcome its limitations. An element of the unexpected is always present. All the variables attendant upon shaping the cloth serve to remove some human control from the shibori process.”

The best shibori pieces often take hours and hours of work stitching and gathering; but after all of the preparation, the cloth is ready to take a dip. One unique feature of indigo is the chemical structure that causes it to change color when exposed to oxygen. The fabric turns a nice, bright green in the dye bath, and only turns blue when it is removed and spread out so that it comes into contact with air. Getting a deep indigo color requires multiple short dips and oxidation periods. The more dips, the darker the shade. Once the cloth finishes its final swim, the bindings are undone, the thread cut, and the cloth unfurled to reveal the final design (as above).

My professor in Rhode Island warned his class that summer that dyeing easily becomes addicting. The first time, I created my dye bath meticulously and thought carefully about how to manipulate the fabric, but before I knew it, I started reaching for any cloth in sight and tossing it into a pot of something. I have found dyeing to be exciting, adventurous, and, yes, even a little addicting. “Chance and accident,” as the World Shibori Network notes, “give life to the shibori process, and this contributes to its special magic.”

Interested in learning more or taking up shibori yourself? Follow the links below!

・Shibori: The Inventive Art of Japanese Shaped Resist Dyeing, by Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada

・Stiched Shibori, by Jane Callendar

Elsa Lagerquist grew up in Pittsburgh but has settled into Midwestern life. After studying literature and art at Hillsdale College, she moved to South Bend, IN to teach middle school girls. Elsa is an aspiring textile designer, but dabbles in all sorts of crafts from calligraphy to crocheting. She also loves to bake and can often be found in the kitchen whipping up a double-batch of cookies. Perhaps more than anything, Elsa looks forward to the day when she can walk out into her own backyard and return with arms full of beautiful, freshly-cut flowers. Visit www.elsakdesign.com to view her work or shop her collection of shibori scarves.

One Comment

Pingback: