by Nick Fox

In her collection of essays Ex Libris, the journalist and unapologetic bibliophile Anne Fadiman makes the distinction between carnal and courtly lovers of books. For a courtly lover, “A book’s physical self is sacrosanct to her, its form inseparable from its content; her duty as a lover is Platonic adoration, a noble but doomed attempt to conserve forever the state of perfect chastity in which it had left the bookseller.” Courtly lovers have pristine bookshelves. They’ll watch you as you leaf through one of their books but probably won’t let you borrow it. Then there is the carnal lover of books, for whom “a book’s words are holy, but the paper, cloth, cardboard, glue, thread, and ink that contain them are a mere vessel, and it is no sacrilege to treat them as wantonly as desire and pragmatism dictate. Hard use is a sign not of disrespect but of intimacy.” The carnal lover is known to underline passages, bend or rip out pages, and leave historical book markers, such as plane tickets or receipts from abroad, tucked away in the text block. Whenever you read a book that was owned by a carnal lover, it’s like watching a movie with someone talking. If you find yourself mentally cataloging your own books, like you were taking a personality test, then you are probably some shade of bibliophile. For bibliophiles, their books are mirrors of their character, and we judge ourselves by the relationship we maintain with our books. An unlikely group of six books made me confront this part of myself.

Before my second child was born, I disassembled the bookshelves on the second floor so the room could become a nursery. I promised my wife I would thin out my collection, and started a pile. Once my unofficial library was reconstructed in the basement, I took the pile that didn’t survive the forced relocation to the used book store. I promptly traded them for new ones. I followed the letter of the law and fulfilled my promise to my wife. Of my original pile, the bookstore rejected six, which I planned to take to Goodwill later. However, the baby came and the books were forgotten on the front porch, later becoming slightly disfigured under the push and pull of the Minnesota winter. Time passed. One nondescript Saturday, my wife moved the brown bag of six books to the back deck during a bout of spring cleaning. I caught sight of them through the blinds of the window that afternoon right as a spring storm started to brew. The pile was like a baby Oedipus left to be ruined by the elements unless some passerby or god took mercy. I put on my shoes and tripped over the uneven deck boards as I cradled the bag of books toward the garage. The pile of six sheltered in the garage on a workbench, homeless. Then the quarantine hit.

During the quarantine, I spent a lot of time woodworking in my garage. Where else was there to go? The bag of refugee books kept popping up and getting in the way. I had to confront their homelessness. While some people were stocking up on toilet paper and rice, I was trying to figure out how to get rid of used books. Because of various quarantine rules, Goodwill wasn’t taking new donations and the Little Free Libraries in my neighborhood were taboo. I considered recycling, the logical green choice, but that didn’t appeal to me. Out of frustration, I considered burning them. Cinematic images of Nazi bonfires and the Library at Alexandria engulfed in flames simmered in my head. Burning a book was repulsive to me, like resorting to cannibalism for survival. None of these options fit. I was surprised to find that this seemingly simple decision of finding old books a new home became a moral dilemma. I took them out of the bag and looked at them one last time before determining their fate.

One was the Viking Portable Faulkner and on the cover is an intense charcoal drawing of Faulkner. My older brother’s girlfriend, Rachel, gave me this book after I graduated college. In the front on the flyleaf, the proper place to write an inscription according to Fadiman, she wrote:

Nick,

I know that whatever decision

you make will be the right one,

and I promise not to ever hassle

you about it.

But so you know how I feel,

please read Two Soldiers before

you decide for sure to go away.

Love,

Rachel

Published in 1942, Two Soldiers is about a ten or eleven year-old boy that trails after his older brother when he leaves to join the Army. As you follow the younger brother, you fall in love with his dogged choices. He takes a bus by himself, speaks with conviction at the recruiting station, and finally the sheriff unites the two separated brothers. The older brother, a boy himself, tells his younger brother to get home because mother is probably worried and it’s not good to worry mother. The plucky little brother reluctantly agrees and you get the impression that the little brother has more courage than any of the adults in the story. The little brother goes home to his mom and the older brother goes off to war and dies. I cried. At the time, I knew I was going to deploy to either Iraq or Afghanistan. I told myself I wasn’t going to read any more war stories before my deployment. At the time, my choice showed I believed in the Army more than I believed in fiction.

Also in the stack was a hard cover book called The Stories of the Persian Wars. On the cover was a section from the Parthenon Frieze nicely enclosed by symmetrical meanders and decorative leaves. The spine displayed a cartoon of a profiled Pericles and inside splendid Art Nouveau plates preceded every other chapter. The book was broken and falling apart like most things from ancient Greece. This book was given to me by a woman named Leela. Leela is an octogenarian who sold her childhood house to my parents. She was the granddaughter of the original architect, Charles Ames, who started building in 1884. She knew I taught classics and gave me this book at the annual 4th of July neighborhood celebration. Leela’s decorum when she presented me the gift cemented something irreplaceable in my mind. I imagine she never expected me to read it, but in her gesture she was passing some sort of torch to me. Now the book was a hallowed memento. I flipped open the cover to the fly leaf that had come detached from the binding. After reading it, I realized that this might have been Leela’s dad’s book from his high school classics course. In graphite cursive was a little ditty from a precocious teenager. It says:

“Charles Lesley Ames

These are his names!

But nobody blames

Charles Lesley Ames!”

~

When he kisses the dames—

added by

himself.

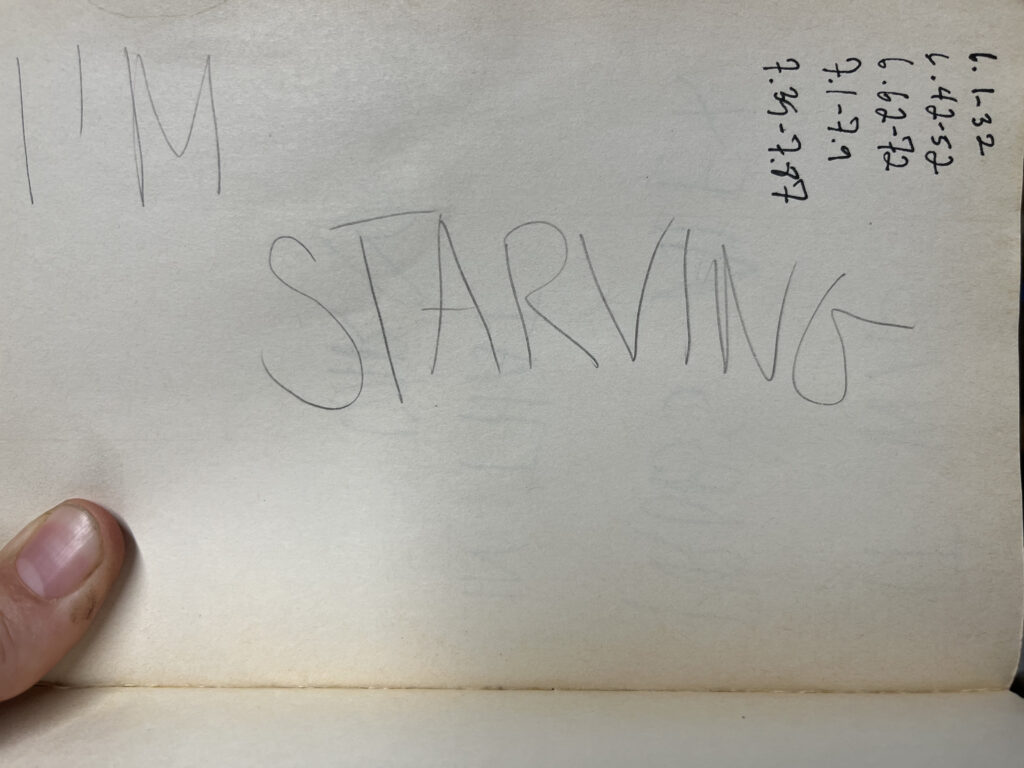

There is another high school book in the group: my youngest sister’s copy of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, complete with her personalized notes, a history in its own right. One example is on page 47, where Thucydides describes his method and justifies why his history is trustworthy. My sister comments in the margin: he himself is correct, obviously. That one underlined word says volumes. On page 155, my sister summarized Thucydides’s dire conclusions about human behavior during the pandemic in Athens, writing: we think we’re good; naturally savages. I don’t know if I’m more impressed with her cool acceptance of the brutish nature of humankind or her adroit use of a semicolon. In addition to her notes on the text, there are marginalia intended for whatever classmate was sitting near. Good gossip that’ll provide ammo for speeches at her up-coming wedding. Although there is nothing on the fly leaf, the back flap has a note written in large caps, most likely for a friend across the room. The simple phrase captures concisely what’s on most teenagers’s minds while reading Thucydides:

The next book I stared at was The Odyssey of Homer translated by Robert Fagles, a repeat in my library. On the cover is a line drawing of a smiling bearded man in profile with wavy hair and an eye like a fish. The image looked like an enlarged section from a Greek vase. I laid the book flat—a carnal book lover move—so I could see the full image that went from cover to cover. This was the first time I had considered the entire image. The full picture is of two men wrestling, both smiling with fish eyes. I proudly recognized the scene from the story: it was Menelaos wrestling the sea-god, Proteus, from Book IV. I was wrong. It’s actually Hercules struggling with the sea-god Triton. I frowned, both at myself for my incorrect answer and at the publisher for picking this image. It’s like putting a zoomed-in picture of a basketball game on the cover of a book about baseball. It’s the same culture, right? I sincerely hope there’s someone at the publishing company that is just having fun with us.

The last book I considered was The History of Philosophy by William Durant. I acquired this book from my dad’s stack of books kept in brown bags in the attic. The inability to get rid of books must be a family gene. One day, probably in an attempt to hide from cleaning up after a holiday meal, I pillaged through these books. Lots of classics and other college texts of an English Major. Durant and his wife wrote about the Story of Philosophy, Art, and History with humility and wit. I have returned to their works many times to find good anecdotes for teaching large swaths of material to students. However, this copy had all the typical flaws: small script, falling apart, and no longer on my life-long reading list. But, I stole it from my dad so it’s not really mine to give away. Penciled on the backside of the front cover is Bernard Fox 25 Columbus Ave Ny 10023, which is in midtown Manhattan. This is my dad’s childhood apartment but his older brother’s book. So maybe my dad stole it, too. Hoarders and thieves are we; perhaps we should change the family name from Fox to Dragon.

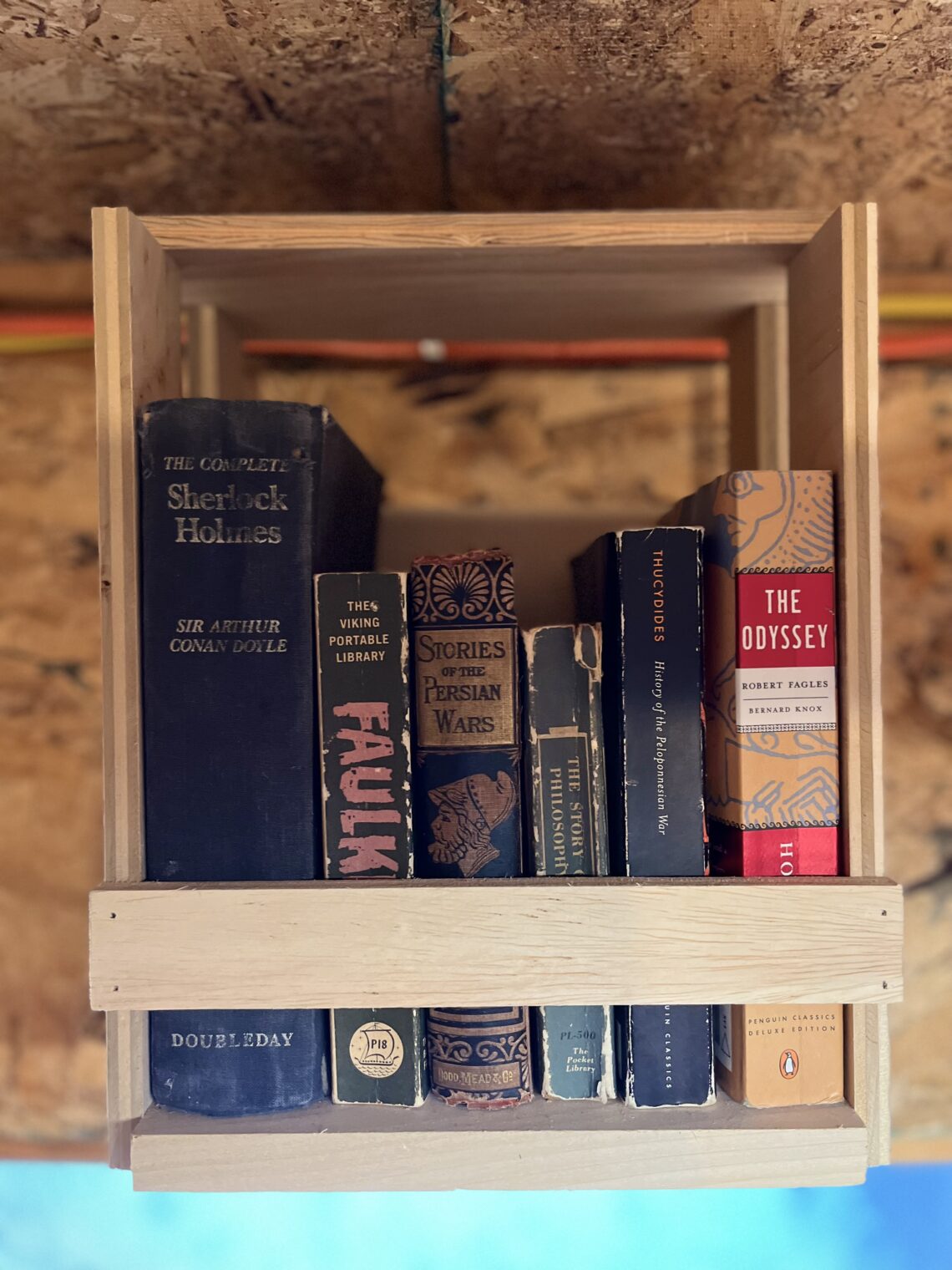

Why I didn’t bring these books inside and squeeze them back into the main bookshelf is beyond me. Instead, a strong gust blew through the open garage doors and something else occurred to me. I Eureka’d so loudly that the dog across the alley barked. I decided to build these books their own private bookcase. They would be a sort of shrine in the garage, a household god looking down. I went to work, grabbing scrap wood and plugging in the air compressor for the nail gun. They all deserved a home together after how they’d been treated for the last several years. They were worthless as books, but priceless as personal artifacts. They’d survived their journeys separately and now together, an unlikely and motley fellowship. Now we quietly ignore each other and go about our business, fully aware of our awkward history together.

Nick Fox lives across the street from a beautiful graveyard in

Minneapolis with his wife and kids. He writes in the basement,

bathes outside, does woodworking in the garage, but usually cooks

in the kitchen.

Header Image: The Six Unwanted Books, by the author.

2 Comments

Nathaniel

Very fun, and oftentimes funny, essay. My free little library is always open to a bibliophile like you.

Sylvia Ryan

A most enjoyable, relatable read!