by Jonathan Peasley

What is of most importance in educators themselves is a respect for the soul as well as for the body of the child, the sense of his innermost essence and his internal resources, and a sort of sacred and loving attention to his mysterious identity, which is a hidden thing that no techniques can reach.

Jacques Maritain

There are two challenges of reading Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, both of which involve overtaking the culturally pervasive portrayals of Ebenezer Scrooge’s journey that many of us are already familiar with. The first challenge is viewing Scrooge as a cartoon character rather than a real, flesh-and-blood human being. In fact, he must undergo not only a moral transformation but also a spiritual one, not unlike those undertaken in more ‘advanced’ literary works like Homer’s Odyssey or Dante’s Inferno. The second challenge facing a reader is the tendency to prejudge the book as a simple morality tale: “Be generous, not greedy.” The story is really an opportunity to witness the mysterious path to human awakening. But the novel first has to be rescued from the cliched moral truisms and sentimentality we’ve come to associate it with. Scrooge’s awakening can mirror

Though we ought to try to rescue Scrooge from a more (literally) cartoonish representation, Dickens himself is partly responsible for humorous characterizations of his main character. (For instance, when he introduces Scrooge, he tells us that “even blindmen’s dogs” appeared to know him; and “when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts.”) But Dickens’s comical descriptions of this old crank aside, the work of engaging the serious questions presented by the text starts with reading Dickens’s own descriptions.

The sprawling portrait of the Spirit of Christmas Past in Stave Two can be startling to revisit. We may already have a picture in our heads of this Spirit being some variation of a luminescent child in adult-form. But Dickens offers us a more concrete image of one aspect of the Spirit’s appearance: it is a candle, and it carries “a great extinguisher for a cap…under its arm.”

Though the use of a light as a symbol for memory seems simple enough, we learn something profound about Scrooge when he almost immediately has a “desire to see the Spirit in his cap; and begs him to be covered.” The Spirit’s response shows us that the cap is of Scrooge’s own making. “Is it not enough that you are one of those whose passions made this cap, and force me through whole trains of years to wear it low upon my brow!” Why has Scrooge come to ignore his own memories? And what “passions” seem to be responsible for this?

A lighter reading of the story might suggest an obvious answer: his greed. But this shortcuts the hard work of grappling with a real human being. Which particular path leads Scrooge to greed?

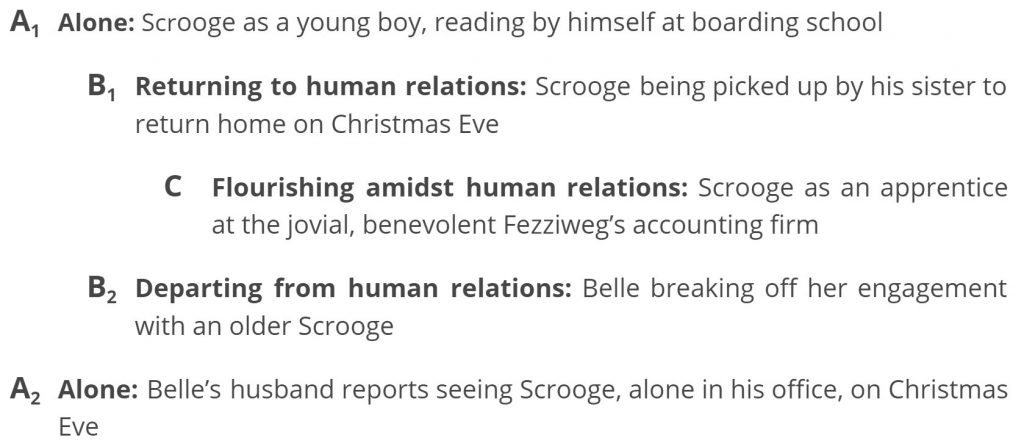

Dividing up the five scenes that the Spirit of Christmas Past shows Scrooge, his past appears as a chiasmus – a pattern that rises and then returns by another route to the same place.

This is the path Scrooge has taken through life, and he must confront it head on. Just as the first image of the abandoned, lonesome boy garnered Scrooge’s tears of pity, at the same image of himself as an adult Scrooge exclaims he “cannot bear it!” He then immediately wrestles the Spirit to the ground to put its extinguisher “cap” on.

Why does Scrooge find his own memories unbearable? The scene when Belle breaks off their engagement provides crucial insight into Scrooge’s character:

“What

idol has displaced you?” Scrooge rejoined.

“A golden one.”

“This is the even-handed dealing of the world!” he said. “There is nothing on which it is so hard as poverty; and there is nothing it professes to condemn with such severity as the pursuit of wealth!”

“You fear the world too much,” she answered, gently. “All your other hopes have merged into the hope of being beyondchance of its sordid reproach.”

According to Belle’s insight into his motivations, Scrooge’s greed is directly connected to his desire to avoid returning to the pain of his childhood.

The reason for being sent off to boarding school in the first place is not explicitly given. But Scrooge’s sister does exclaim, “Father is so much kinder than he used to be!” With that, we see Scrooge’s trajectory into adulthood more clearly. His childhood is painted as being much more dire, if not also traumatic, than a generic depiction of a loss of innocence via coming of age. Instead of just a superficial lust for gold, the greed of his adult self is rooted in his own human desperation to avoid returning to the poverty, implied abuse, and solitary misery of his childhood. But it is precisely this fear itself that has become a tragic flaw and self-fulfilling prophecy. Though he finds it unfair that there is nothing the world “professes to condemn with such severity as the pursuit of wealth,” he has become blind to the extent to which his own ambition is driven by an unquestioned fear.

Belle’s attempt to rescue him from his own blindness by scrutinizing the direction of his life seems to be what wounds Scrooge the most. He can now see clearly that his life in its current state is the consequence of his own free choices. It seems to be at this point that Scrooge understands Marley’s warning that the chain he wears is one he “girded of my own free will, and of my own free will wore.”

We also see that Scrooge’s fear of the world was misplaced. The source of true misery was within him all along. When he was alone at the boarding school, he was actually rich in his own faculty of imagination, able to conjure characters from the literature he read with seeming ease and delight (“It’s Ali Baba! There’s the Parrot! Poor Robin Crusoe!”). But as an adult, he appears to have forgotten that even when he was physically alone and poor he was interiorly anything but. We see that Scrooge had an inner richness that was lost – but not because of what the world had done to him. Rather, it was lost through Scrooge’s own instinct to forget his origins and escape those deeply held memories that make him who he is. His outward poverty and inner richness were, at some point, tragically forgotten, or mistaken, or both. Scrooge’s journey with the three spirits is thus not simply a supernatural intervention that is done to him, but rather an awakening of his own basic human capacities for memory and imagination. As one of my students once claimed, it is by remembering the past that Scrooge is then able to imagine a different future for himself.

This connection between memory, imagination,

If we return to Belle’s diagnosis, “You fear the world too much,” it offers insight not just into Scrooge’s character and how it was shaped, but even into a truth of the human condition. Scrooge has, through his own free and blind choices, fulfilled his own greatest fear – that of being alone and miserable. But if to be human is to share in Scrooge’s spiritual affliction, it means we also share in its balm. By showing us the profound impact of the “simple little air,” we see that the means of Scrooge’s radical reformation are his senses, awakened. The music of the past is infinitely present to Scrooge’s soul. He himself can alter his trajectory: from one that flees to riches out of fear, he can become one who pursues the goodness that cannot die but is only ever forgotten.

Thus does Scrooge give us an opportunity to glimpse, to repeat Maritain, a “sense of his innermost essence and his internal resources, and a sort of sacred and loving attention to his mysterious identity.” Though Scrooge undoubtedly did not cultivate fertile ground within himself in the course of his life, the seeds of his own regeneration had been planted in him all along.

Coming into a view of Scrooge’s soul gives us more than just a simple illustration of the obvious – that greed is bad and generosity good. It reflects back to us the intermingling of our own freedom and the origins and memories invested in us by destiny. By encountering Ebenezer Scrooge as a human being, we also encounter ourselves. We are not simply creatures with the capacity for choosing good and evil, but intricate weavings of fate and freedom, intellect and sense, memory and blindness. By awakening to Scrooge’s humanity, we awaken to our own.

Has it been a while since you have read A Christmas Carol? Pick up a copy for yourself, click here to read the Internet Archive’s edition (with illustrations by Arthur Rackham), or click here to listen to the tale read by Smokestack Jones at LibriVox.com (alternative version here read by Kara Shallenberg.)

Jonathan Peasley lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he teaches Latin, mythology, writing, philosophy, and literature. He spends his extracurricular time savoring the surprises and delights of poetry, trails and lakes, fatherhood, music, and world cinema.

One Comment

Tom King

I haven’t seen a quote by Jacques Maritain since I was myself a younger lad….in college and reading: “Existence and the Existent” for a PH 101 course.

M. Maritain’s writings, and what I could make of it at the time, intrigued me then as it still does. Plus an English course in Victorian litertature that opened up to me Dicken’s insights delights, of which Scrooge was clearly one.

Thanks to Mr. Peasely for another helpful journey amidst the ghosts. Keep that Veritas churning.

Tom