by Dominic Bulger

“I don’t know, I guess opera’s just not my thing,” I concluded, slouching against the wall of the music building hallway. After travelling across the state to Western Michigan University for a vocal competition, I’d sung some operatic repertoire for a panel of judges. Later in the day I received feedback from the judges, confirming, in part, what my teacher had been telling me for weeks. Be more expressive with your face. Don’t just stand there and sing as if the words had no meaning. Act! I was grappling with the reality that the performer of opera is just as much an actor as he or she is a musician. My first reaction to this critique was an objection. I didn’t come to a vocal competition to act—I came to sing!

My growing awareness of this problem in my performance frustrated me. I had strutted into this competition expecting trite praise, “nice job” and “keep up the good work.” Being startled then by failure where I expected to find success, I retreated from the situation. I was not so bold as to argue against opera’s artistic value. But I was willing to say that, while I “respected” opera and “could see how it is valuable,” it “just wasn’t my cup of tea.” I would never engage in the active destruction of opera, I claimed. But I was willing enough to let it be forgotten. If the iconoclasts had come to destroy the memory of opera that day, I honestly might not have stood with its defenders.

Fortunately, I had a friend in that Western Michigan hallway with me who did not let my patent dismissal of one of the defining genres of Western music go unchecked. She lectured me on the sheer technical ability it takes for one to sing opera professionally. She listened seriously to my complaints and validated me in places where my frustration was justified. She helped me see how opera explores the emotional heights and depths of human life in unique and exciting ways. As she defended opera, I began to see the immaturity of my attitude. I left that conversation with two things: a new awareness of something in opera which I could not yet see and a growing desire to pursue that still-hidden source of beauty. A necessary shift in my approach to the situation occurred when I began to see myself, rather than opera, as deficient. Alongside this realization, I needed the guidance of a teacher—in this case, a friend—who could show me how to love opera. Faced with my own failure, I resolved not to simply dismiss opera as I had originally, but to pursue an understanding of and love for opera.

This is not an isolated experience, but an example of a broader kind of experience fundamental to what education is. We’re frustrated by teachers when they ask for more than their students are capable of giving. We’re frustrated at ourselves when we find ourselves unable to give what we’re asked for. I vividly remember being infuriated when my eighth-grade literature and composition teacher ended a futile discussion, saying, “Maybe you guys just aren’t old enough to talk about this yet.” When I read Crime and Punishment in tenth grade, I struggled just for basic comprehension of the text, often feeling unable to contribute to class discussions. In a certain sense, I had no business reading Dostoevsky, and I knew it. But attempting to read Dostoevsky as a tenth grader educated me on another level than merely what I could glean from the novel. In an upper-level undergraduate seminar on Shakespeare this past fall I was constantly amazed by the elements my professor and peers would pull out of the text—important, essential details which I had simply missed in my own reading. In all these situations throughout my education, I have been made keenly aware of my own immaturity and inadequacy.

In these moments, it can be tempting for the student to simply dismiss the subject at hand as boring or just plain too hard, to say, “I guess opera’s just not my thing.” It is just as easy to follow the opposite inclination and accuse oneself of “not being a math person.” Both of these attitudes are rooted in a misunderstanding of the key role failure plays in education. These moments may seem like roadblocks on the path of education, but it is in these moments where education truly happens. As a violent encounter in a story of Flannery O’Connor can open a character to receive grace, so too can a painful discovery of one’s own inadequacy provide a space where the student can truly learn. When I read difficult literature or try to sing opera, I encounter a self that is weak, lazy, young, inexperienced, incompetent, and, despite all those things, proud. I am thrown back upon myself, brought to a place where I must decide which will give in: opera or me.

Dominic Bulger is a student at Hillsdale College, majoring in music with a focus in cello performance and minoring in English. He loves singing with his friends in the choir, in his bands on campus, and in his living room. He also enjoys hosting dinner parties, and reading poetry with his friends. A native of the great state of Minnesota, Dominic jumps on the chances he gets to spend time outside hiking, running, and camping.

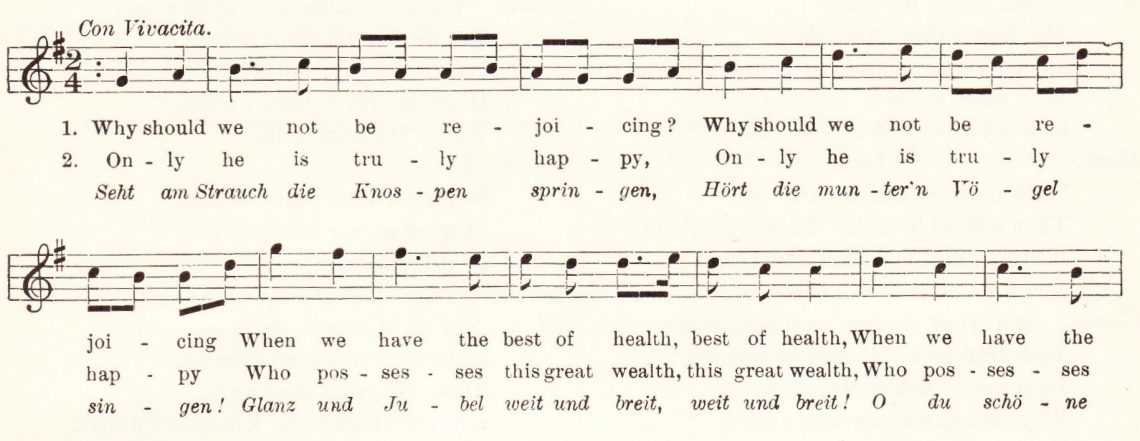

Header Image: Music for the opening chorus of Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride (public domain)

5 Comments

Anne Brewer

Thank you Dominic! Great insight.

Nancy Grams

Mature insights written with humility and grace!

Thank you, Dominic!!

Lisa Krueger

Written beautifully, with depth and grace.

You’re good Dom! Thank you!

Mary Claassen

I often feel so inadequate and small and unable to understand scripture. That’s where I’m at. I feel like it doesn’t penetrate my hardness of heart in the moment. It is good to read your experiences. It makes me want to push deeper and cry out for more of the spirit.

Andrew Gaylord

What a thrilling read! Thank you, Dominic, for defending the great and overlooked power of inadequacy.