“This Is the War Against Human Nature,” by Paul Kingsnorth in The New York Times

So asking yourself if you can step outside the system is almost the wrong question. The question is what relationship you can have with it and where you can draw your lines. What do you want to do with technology, and what do you want it to do with you?

I think if you don’t define your relationship with the machine, it defines it for you. And that’s true of all of us. We can be different degrees inside and outside the system, maybe, depending on where we are. There are levels of relationship, but it’s a time when we’re all caught up in this thing. It’s been building up for a long time.

“Unquenchable Fire: The Road as a Graphic Novel,” by John Hendrix in Image Journal

Both The Day After and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road use the same magic trick: They transform deep fears from abstract possibility into granular particularity. Like The Day After, McCarthy’s 2006 novel became an instant cultural touchstone. On page one, we enter in medias res, without explanation or preamble. The entire world has been destroyed; only a heap of ashes, bodies, and wreckage remains. A father and son are on a journey south, searching for a warmer climate, adorned in the decayed scraps of a once vibrant world. The unnamed father grasps at the faintest notions of hope to offer his son, but the bleak landscape and a pursuing faction of cannibals suggest a grimmer future.

Manu Larcenet’s 2024 graphic novel adaptation recreates the illusion performed by the original novel, and somehow the wonder of the story has not dimmed. The acclaimed French comic artist spent years on this magnum opus, and it shows.

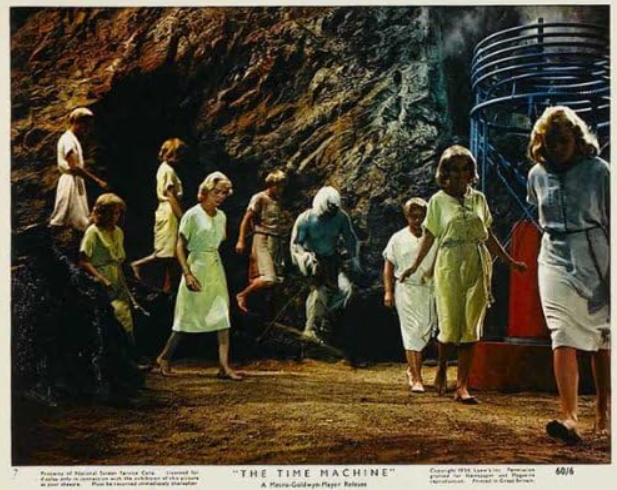

“Eloi and Morlocks,” by Nic Rowan in The Lamp

Sometime last fall I met an aspiring journalist at a bar near my house. We sat, ordered a pitcher, swapped stories. It was all informal shop talk, the pleasant patter of a slow weekday afternoon, until suddenly—I know not how—the film Triumph of the Will entered the conversation. The young journalist lowered his voice and looked around, feigning a furtive tone.

“You know,” he said, “some of that stuff is lowkey based.”

He began to elaborate, a little vaguely, on Leni Riefenstahl’s striking camerawork, before I cut him off.

“It’s a boring movie,” I said. “And Riefenstahl was a better photographer than filmmaker anyway.”

“Sure,” he replied. His manner, before so animated, turned bored, indifferent. I was confused. He was confused. We smiled at each other, but neither of us had anything to say. Not long after, we paid for our drinks and shook hands outside. We never spoke again.

For days afterward I couldn’t stop thinking about the interaction. It wasn’t just that he had implied a certain admiration for the Third Reich—hardly an edgy opinion among online Zoomers—but that he had seemed weirdly, naïvely attached to the idea of Triumph of the Will as a captivating work of art. “It’s a boring movie—these days only film students watch it!” I kept repeating to myself. What are the odds that a based twenty-one-year-old kid hooked on Zyns, with no prior knowledge of Weimar cinema, sat through all two hours of a documentary about a Nuremberg rally? It seemed unlikely.

In fact, it was absurd, as I soon discovered.

“Large Language Muddle,” by the editors in N Plus One Magazine

No topic — not the genocidal war and famine in Gaza, not Trumpian authoritarianism — has magnetized bien-pensant attention this year in the way that AI has. Writing on AI thus comes in every mode: muckraking (“Inside the AI Prompts DOGE Used to ‘Munch’ Contracts Related to Veterans’ Health”), scholastic (“Deep Learning’s Governmentality”), polemical (“The Silicon-Tongued Devil”), besotted (“The AI Birthday Letter That Blew Me Away”). The AI-and-I essay, however, usefully registers a generalized intellectual anxiety. While spoken in the voice of an individual author, each piece in this emergent corpus stages a more collective drama. To read these writers writing about AI writing is to witness, almost in real time, intellectual laborers assimilating a threat to their own existence.

***

A refusal of AI in creative work begins with a refusal of that product’s ideological packaging. “When we imbue these systems with fictitious consciousness,” Bender and Alex Hanna write in their recent book The AI Con, “we are implicitly devaluing what it means to be human.” The way out of AI hell is not to regroup around our treasured flaws and beautiful frailties, but to launch a frontal assault. AI, not the human mind, is the weak, narrow, crude machine.