by Abbey von Gohren

There’s a hundred and four days of summer vacation

‘Til school comes along just to end it

So the annual problem for our generation

Is finding a good way to spend it.

If you were born before 1980 (like I was) or after 2000, you may have missed the phenomenon of Phineas and Ferb. The cartoon ran from 2007-2015 on Disney Network and also produced three full-length feature films. For a certain subsection of millennials – the above mentioned “our generation” – this is a beloved bit of nostalgia. As for me, I didn’t really discover Phineas and Ferb until a year or two ago, while perusing family film possibilities. I stumbled upon the most recent of the two films, Phineas and Ferb the Movie: Candace Against the Universe (2020), and discovered not only a well-written, hilarious world of fun but also a very strong statement about what it means to engage in true leisure.

For the uninitiated, Phineas and Ferb is full of running gags, and though the plot follows a formula, the familiar twists and turns only increase the merriment. Every episode features two brothers who are trying to decide how to spend a summer’s day. As the theme song explains:

Building a rocket or fighting a mummy

Or climbing up the Eiffel Tower

Discovering something that doesn’t exist

Or giving a monkey a shower

Surfing tidal waves, creating nanobots

Or locating Frankenstein’s brain

Finding a dodo bird, painting a continent

Or driving our sister insane

Driving their sister Candace off the deep end is actually an essential piece of the plot. She initially appears as a shallow, shopping-mall-loving, boy-crazy teenager who lives to “bust her brothers.” Her main goal in life is to catch Phineas and Ferb in the act of one of their preposterous schemes and show it to their mom. Predictably, she fails every time. In another delightful, zany subplot that replays, the boys’ pet platypus Perry is secretly a spy trying to keep Dr. Doofenshmirtz, a maladroit, goofball scientist from taking over the world – or at least, the “Tri-State Area.”

If Candace lives for telling on her brothers, and Dr. Doofenshmirtz lives for ruling the “Tri-State Area,” what do Phineas and Ferb live for? To answer that question, we’ll jump into a scene from Phineas and Ferb the Movie: Across the Second Dimension, in which Phineas and Ferb are transported to another dimension where they meet alternate versions of themselves. In this multiverse, summer has been officially outlawed, and the two doppelgangers remain at home, huddled in fear of doing something against the rules.

Phineas: You guys don’t have summer? Well…that’s…that’s terrible.

Phineas-2: Summer. It sounds dangerous yet oddly compelling. What is it?

Phineas: What is summer? Man, where do I begin!

To re-introduce their alternate selves to the reality of summer, they sing a song:

It’s summer, every single moment is worth its weight in gold.

Summer, it’s like the world’s best story, and it’s waiting to be told.

It’s ice cream cones and cherry soda dripping down your chin.

It’s summer, and where do we begin?

They prize summer above all else. Why? It is full of potential, and unfinished narratives, embodied experience, and sensory experience with others. “Summer” becomes a stand-in for a life well-lived in the particulars. It’s making-do with the odds and ends we’ve been given, bucking convention, and rising to the occasion, as the final portion of the theme song expresses so well:

We’ve got our mission and some pliers

Yogurt, gumballs and desire

And a pocketful of rubber bands

The manual on handstands

A unicycle, compass

And a camera that won’t focus

And a canteen full of soda

Grab a beach towel

Here we go!

It’s easy to reduce this approach down to “living in the moment” or some other instagram-worthy caption, but Phineas and Ferb have a bit more to offer us under the surface. They may be out of school, but they are remarkably attuned to a deeply satisfying philosophy of learning. They would never say this, of course – the whole point is that they’re immersed. Aside from a great side gag about existentialist trading cards (“Kirkegaard. Came with the gum.”) the brothers are blissfully unaware of their own phenomenological positioning. It’s up to us to stand back for just a moment in order to understand how truly revolutionary their winsomeness and wisdom is from an epistemological perspective.

In the show, “school” represents a kind of narrow way of life from which kids are liberated. We all know that exhilarating feeling near the end of May, but except for students and career teachers, this tends to fade over time and a new anxiety about “what will we do with the kids over the summer” takes over. Frantic parents scour the camp offerings, sweat over waiting lists, and try like the dickens to make sure their kids are having a “good time,” all the while needing to balance their own work lives. It is undoubtedly difficult to manage and childcare over the summer is a very real necessity for most families in one capacity or another. Regardless of family schedules, however, there is a distinct need to rediscover what leisure is, and also what its connection to learning is.

As Polanyi disciple and philosopher Esther Meek puts it, we are in need of “epistemological therapy.” We have inherited an “epistemic default” that we don’t even realize is operating, one which mistakenly contrasts “facts” with “opinions,” ‘objective truth” with “subjective experience,” and “theory and science” with “art and imagination.” In addition, the fact/objective/science side of each of these pairs are also seen to be more accurate or “real” as knowledge from the perspective we have received in Western thought, especially given the influence of René Descartes. Phineas and Ferb’s take on the narrowness of school may seem to reinforce a similar, simple dichotomy (school = bad; summer = good), but they are actually offering a third way and through it, a vision for education and the good life.

In our current American culture, the simple dichotomy plays out in the following way. We think that time and activity fall into one of two possible modes: study/work and “chilling out.” These are mutually exclusive. The first corresponds to any program that enables us to acquire factoids and accumulate “experiences” – whether it’s a kid in summer camp doing the prescribed activity according to the rules or an adult collecting data to put in a spreadsheet. The second is a ”vegging out” – which most of us end up doing on screens these days, of course. Is there any life outside these two modes?

Leisure, à la Phineas and Ferb, presents a vision for what this might look like. What they model is a phenomenological approach to knowing about the world, which is neither acquisition of facts, nor total disconnection and “zoning out.” School may be out, but Being-in-the-World is in.

Being-in-the-World was Heidegger’s great phrase that described how our minds and bodies are not as separate as we have been led to believe (another aspect of that epistemic default mentioned earlier) and also that our selves are somewhat permeable by the things around us. French existentialist Maurice Merleau-Ponty took this and ran with it, arguing that our selves are kind of porous, reaching into the world, and becoming unified with aspects of it. His way of putting it was that “perception is not a scientific knowledge of the world, but the experience of our inherence in things” (Phénoménologie de la perception de Merleau-Ponty – Autrui et le monde humain (Commentaire) by Bénédicte de Villers, trans. mine ). Not only this, he suggested that the world also reaches into us through our perception, even before we have a conscious awareness of it. Experience is pre-thought, and we gather together impressions as we try things out – through action, and also through conversations.

This is why Phineas and Ferb must go out on a limb (sometimes literally) to just try something and see where it goes. Sometimes that’s in circles. (A favorite family episode at my house is their rocket-powered tire swing!) We are painfully uncomfortable with this mode, though, either because of the risk, uncertainty, or unpredictability. This is where a little child will lead them. Curiosity may be dulled by too much programmatic study and shallow entertainment (the two modes mentioned earlier) even in the young, but that sense of wonder can be rekindled, and much of it has to do with leaving them the heck alone. British education reformer Charlotte Mason dubbed this “masterly inactivity” but you don’t need a fancy name to know what I’m talking about. All it takes is waiting for a late bus with your kids to remember that they are still supremely good at finding ways to participate in the world around them. “Look at the ladybug, mama!” (Swings around pole.) “Let’s play a game!” (Gathers tiny, sour crabapples to nibble on with a wincing face.) What’s more, if I’ve got my phone put away, I get to join in the fun.

And speaking of joining in the fun, what is so great about Phineas and Ferb’s parents is that they are so interested in their own ventures that their kids are left to their own devices. They offer glimpses of what an adult version of what their sons are doing might look like. You find the mom doing an “audiotour” of her hometown, or the dad going to a class for some esoteric sport. It’s a bit of a send-up of chronic hobbyists, but also seems like a sincere representation of leisurely, “out-of-school” learning. Leisure is the highest form of being and the most potent mode for taking in knowledge in the world, and this can be as satisfying for the grown-ups as it is for the kids.

So, however your summer has been looking so far — full of camps, and travel, or perhaps a bit aimless, likely a combination of all of the above — keep in mind that Phineas and Ferb are always out there reminding you that in summer:

It’s summer, every single moment is worth its weight in gold.

Summer, it’s like the world’s best story, and it’s waiting to be told.

If you enjoyed this article, we also recommend Tao Ruspoli’s documentary, Being in the World.

Want to join the conversation? Let us know in the comments below what your best moments of this summer have been so far!

Abbey von Gohren is managing editor of Veritas Journal and writes regularly at her substack Heart Before the Course. To borrow a couple lines from George Herbert, she seeks to better notice “God’s breath in man returning to his birth” with her “soul in paraphrase, heart in pilgrimage.”

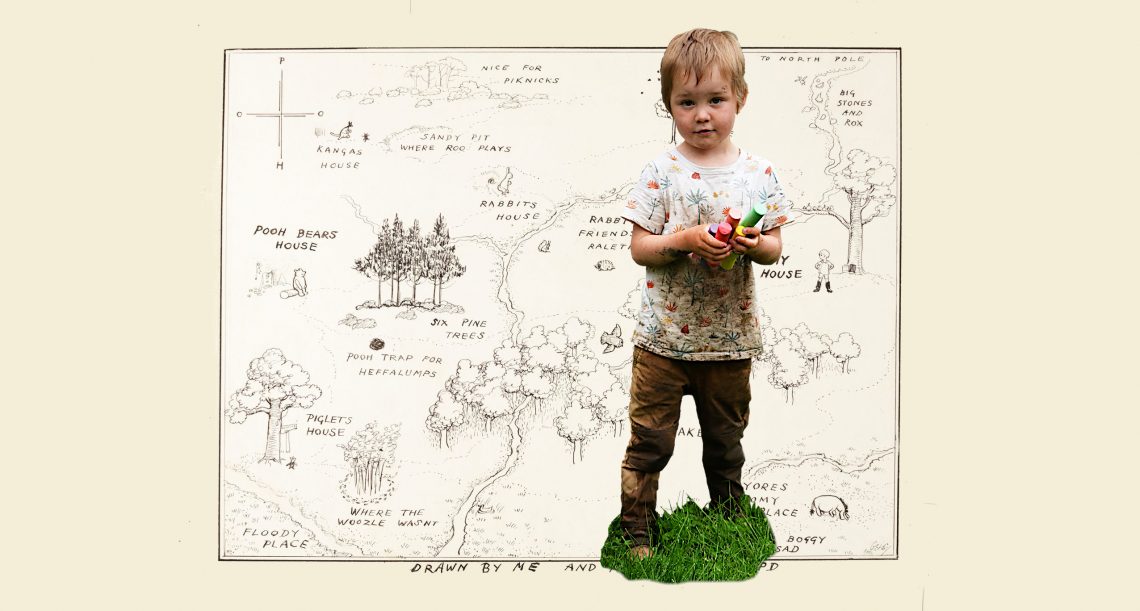

Header Image: © Kairos Photography

One Comment

Henry Lewis

WHAT A DELIGHT! Rollicking fun and packed to overflowing with insight. Love this!