by Jon Balsbaugh

the trouble with poetry is

that it encourages the writing of more poetry,

more guppies crowding the fish tank,

more baby rabbits

hopping out of their mothers into the dewy grass.

— from Billy Collins’s “The Trouble with Poetry”

Reading my colleague Andrew Carr’s recent piece for Veritas Journal (“Self-Portrait After an Election”), I was struck by how the piece shifted dramatically from the raw, disturbing vitality of Francisco Goya’s late work directly to the complete restfulness of a Monet still-life, then moved back through Andrew Wyeth, and eventually settled upon the JoAnn Verburg’s perspective-bending work with a view camera. The piece was a masterwork not only in art appreciation but also in how to weave art into your life and experience of the world.

The most important impact of the piece for me was being introduced to JoAnn Verburg. As soon as I saw her olive trees, I was enamored. This was due, in part, to the fact that we share the same artistic medium — photography. But I also recognized in Verburg’s work a harmony with my own fascination with photography and time. And there was something more. She was altering not only the sense of time but also the sense of space and the intersection of these two.

As Andrew so well put it, Verburg created a situation for the viewer in which:

“Focus could … run into and out of the image, instead across it, as expected. The effect was perplexing within a single photo, and confounding over three, each with its own tilt. Yet these various focal crosssections added up to a somehow richer awareness of the landscape’s spatial relationships than any one of them could have provided. It recalled the deep spatial awareness accumulated from looking out a car window and watching all the various distances, like backdrops in a theater, passing by at different speeds.”

I missed the Verburg exhibit Andrew mentioned in the article by only a few days on a trip to Minneapolis, So I was forced to scour the internet for a lesser alternative, digital images of her work. Fortunately, her artist’s website gives a good overview. The Pace Gallery also maintains an excellent sample of images from her 2021 exhibit. Both are worth a visit.

After reading more about her process, I was hooked. Verburg accomplishes these effects by using a large format view camera to alter the very focal plane of an image, playing with what parts of a photo are sharply in focus or blurred in a way that is not natural to a single human perspective.

Imagine you are holding a rectangular piece of cardboard out at arm’s length, perfectly vertical. This would represent a camera’s normal plane of focus. To “focus” a camera is to move that plane closer or further away from yourself. Imagine, however, that you could flip, twist, and turn that piece of cardboard. This is what a view camera can do to the focal plane of an image.

As someone who does not make a living at photography, however, I work on a limited budget. I could never afford Verburg’s large format view camera, let alone the film required to shoot with one or the darkroom set up to develop it. Nor did I have the time, patience, or skill to manually convert a view camera for use with a standard digital camera. Enter the tilt-shift lens.

While not quite as flexible as a view camera, a tilt-shift lens can accomplish similar effects. Even tilt-shift lenses can be spendy. A professional-grade lens might run around $2,000. However, I was able to find an entry-level lens with solid reviews and fit my “Christmas money” budget, the TTArtisan 50mm 1.4. When it came in the mail I unboxed it and got straight to work.

At first, all I was doing was experimenting. I wanted to introduce myself to the lens not by reading about it but by playing with the dials and knobs. I wanted to find out “what happens when.” I wanted to experience from behind the lens what I had experienced in the finished product to the greatest extent possible. Experimenting in this way worked to create the spatial and temporal disorientation I was hoping for as an artist. I found myself consistently wondering what I was seeing and what was going on in the relationship between the camera, the world, and myself.

At first, I was unsure how to adjust for the desired results. I struggled to make particular effects appear. Then, slowly, I made progress in understanding what happens when you tilt the lens, what happens when you shift it, and what happens when you combine those effects in a variety of ways.

Some of my early experiments were crude exercises like the one pictured here. I simply wanted to see if I could get my wife’s face and coffee cup both in focus; so I played around with the tilt-shift until that happened. After a certain amount of this kind of experimentation, though, it became clear that it was time to begin learning more. So I started looking at the manual, reading online explanations, and watching a few YouTube videos. Nonetheless, that early, freeform experimentation was essential to the artistic process. There is a tacit dimension to all art, and learning too many technical tips too early can get in the way.

With experimentation and second-hand knowledge, I now started to develop a greater command of the tilt-shift effects. I could predict the outcome of my adjustments and their impact on the image, even if imperfectly. And I was developing a greater understanding of what was possible.

At one interesting urban site with a lot of depth and structure, I experimented with multiple settings, each one producing a very different sense of the space. Here are two that illustrate well the dynamism of a tilt-shift lens. As you compare them, give yourself time to work your way around inside each photo.

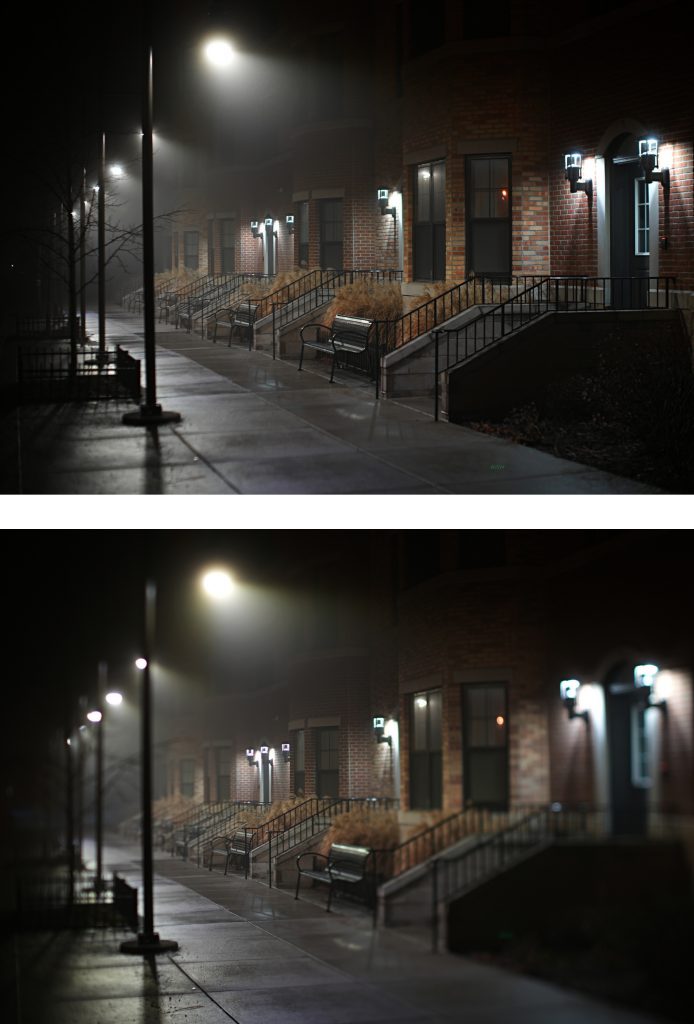

Here is another set of tilt-shift perspectives from a recent foggy night. The effect is subtler here, but the settings affect the amount of room you feel like you have to move around inside each photo. One almost invites you to stroll through and keep going while the other says, “Sit here a while.”

As I learned to work with the new lens, I began trying it out on portraiture, rural landscapes, street photography, candids, abstracts, nature shots — even sports photography. For a month, if I was shooting it, I was shooting it with the tilt-shift lens.

Below are some of the results. Even in my own estimation, most of them range from clunky to moderately interesting experiments. A few of the shots, though, really do at least come close to some sense of beauty within a fractured space-time continuum. Those I may let rest for a while and return to later. (Click for full images.)

Finally, after a month of working with TTArtisan, I was able to take it on a trip to New York City. While there, I wanted to give this way of seeing the world the ultimate test. Could I use these tools to explore and communicate a new experience of what it means to be human?

One of the many paradoxes of New York City is the opportunity it offers to encounter so many distinct individuals in the midst of an overwhelming mass of humanity. For a boy who grew up in a town of five hundred people in the grass seed capital of the world, the diversities, eccentricities, and idiosyncrasies of each person are matched only by the overwhelming volume. Every time I visit New York, I see faces and figures that forever remain in my memory as particular people. And every time I visit New York I am overwhelmed by the crowds. What I wondered when I walked out onto the streets of Midtown Manhattan this time was, “What would happen if could eliminate this feature from New York City?” My method was to narrow and adjust the focal plane so that it would appear just above the heads of the people on the street, obscuring not only their identities but to some extent even their existence as a crowd.

I wish I had a week in New York to keep shooting, but I was happy with these results.

Neither the individuals nor the New York City crowd dominates the space-time of these images. Even though the streets are dotted or crowded with spectral shapes and figures, the city feels silent and nostalgic. These shots capture, for me anyway, “empty streets too dead for dreaming” that are dreamscapes nonetheless.

No, I am not an expert yet in my use or even understanding of my tilt-shift lens. A little over a month into this learning process, I am still years away from the subtlety and command JoAnn Verburg’s olive trees demonstrate. But that’s not the point. As G.K. Chesterton once pointed out, “If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.” And almost everything worth doing is done badly at the beginning. So if you see art that inspires you to see the world in a new and fresh way, pick up that brush, that sketchpad, that guitar, tin whistle, or tilt-shift lens. “The universe is full of magical things patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper,” and the artist in each of us ought to rise to meet them.

Jon Balsbaugh is the founder and editor-in-chief of Veritas Journal and, owner and operator of Kairos Educational Consulting. Though his soul still imagines itself in the Pacific Northwest of his childhood, he now lives in South Bend, IN. He and his wife have five children. Mr. Balsbaugh has been involved in classical education for nearly thirty years as a teacher, administrator, speaker, and consultant. In addition to reading, writing, and thoughtful contemplation of ideas, he enjoys seeing the world through the lens of his three primary hobbies: fly fishing, foraging, and photography.

header image: Untitled, © Kairos Photography (2025)