by Jon Balsbaugh

No one, it seems, argues that letter or number grades serve the pedagogical function of forming students intellectually, morally, aesthetically, spiritually, physically, practically, or socially. Nor does anyone suggest grades are intrinsic to or especially useful for helping students nurture a posture of wonder, a creative imagination, intellectual appetite, depth of inquiry, verbal eloquence, intellectual honesty and humility, moral and spiritual seriousness, physical health, sensitivity toward beauty, concern for truth, or love of God, country, and neighbor.

— Dr. Brian Williams, “Teaching Students to Feel Pleasure and Pain at the Wrong Thing: The History of Grades and Grading”

One of my favorite bits of cinematic dialogue is from a scene in the 1996 film, Big Night. The film stars Tony Shalhoub and Stanley Tucci as Primo and Secondo, two immigrant brothers trying to make a go of it with Paradise — an aptly named Italian restaurant on the Jersey shore. Primo, the elder brother, is the chef and culinary purist. Incensed at the vulgarity of the American palate, he refuses to compromise on food quality. Secondo manages the business end of the operation. While also a lover of fine Italian food, he recognizes that running a successful restaurant in America may require some degree of compromise — especially if the competition is willing to cater to existing market demand. With the restaurant on the verge of financial collapse, Secondo hatches a scheme. The restaurant will host one last evening of the finest Italian feasting that could be imagined with the legendary Louis Prima in attendance (the “Big Night”). If Louis Prima is wowed, the restaurant’s future will be secure. But first Secondo must convince his brother.

Secondo: What’s the matter with you? Are you sick?

Primo: People should come just for the food.

Secondo: Primo, I need your help here, okay? Louis Prima is coming! He’s not just some guy, he’s famous!

Primo: Famous? Is he good?

Secondo: He’s great.

Primo: People should come just for the food.

Secondo: I know that.

Primo: They should come just for the food!

Secondo: I know that, I know. But they don’t.

Sadly, we no longer live in the Garden or dine in Paradise. We may be on a pilgrimage of return, but for the time being, we find ourselves definitively east of Eden. They should come just for the food. But they don’t.

In the first three parts of this series, I have tried to make the case that grades are an unnecessary feature of industrial and modernist influences on education. The kind of numerical precision often associated with grades is foreign to true professional assessment, and grades are one of the main contributing factors to the erosion of proper “leisure” in education. I have been taking up Primo’s side of the argument. But it is time to give Secondo his due and embrace at least some practical accommodations.

For most schools, teachers, parents, and students, grades will continue to be a part of their reality. Grades are baked into the system. Though I find them unnecessary and even destructive, I have never taught in a school that didn’t issue grades. Even as an administrator, I could not have eliminated grades without unleashing chaos. So our school had grading policies, tried to ensure fairness, assigned grades, and generated grade point averages.

Grades may not be going anywhere soon, but for those who would prefer not to grade, there is still plenty of room to operate in the space between pure idealism and rank hypocrisy. Even while assigning grades, a school can establish policies designed to mitigate the worst effects of grade consciousness. Those things do matter. And though a teacher may have to assign a grade at the end of the day, she can still create a culture of learning in the classroom, focus on the content of the course, and teach the students in front of her. At the conclusion of this article are eight practical tips for teachers and administrators wishing to reduce grade consciousness.

We should never forget, though, that the most important thing a school can do to push back against the negative effects of grades is to focus on the true, the good, and the beautiful. Nothing dims the consciousness of lesser things like the enlightening apprehension of higher ones.

Eight Tips for Creating a Less Grade-Conscious Culture

1. Host an annual “fireside chat” for parents on grades and grading.

Regardless of a school’s position on grades, parents need to know that the school understands their concerns about student performance, college admission, mental health in relation to grades, etc. A school might hold an annual meeting on these topics for new parents, first-year upper-school parents, or any parents who wish to attend. The school leader should definitely use such an opportunity to cast a vision for assessment and evaluation. The most important part of such a meeting, however, may end up being the question and answer time at the end. In that exchange, the school will gain invaluable insight into the real-time experience of parents and their children. Actively listening to that experience will help the school guide this conversation.

2. Resist grade-consciousness in students.

Grade-consciousness can spread in the school culture as fast as a winter cold. It is bad for the students themselves, it is detrimental to their learning, and it has a corrosive effect on the culture. A teacher should resist engaging students while they are in a mode of hyper grade-consciousness. This does not mean teachers should leave the students without guidance on how to improve their performance, of course. But student anxiety about grades should be transposed into a higher key. “What do I have to do to get a better grade in Geometry?” is not the same question as “What does a truly excellent understanding of Geometry look like for someone my age?” The former question is likely to be answered in terms of homework, quizzes, and tests. The latter question opens up more interesting avenues for discussion. Faculty should teach students how to ask questions about particular knowledge they want to gain and skills they want to improve. And they ought to teach them to strive for excellence, not the grade. The appreciation and pursuit of excellence plays a key role in classical education. Grade consciousness and grade chasing are poor substitutes at best.

3. Foster an appreciation for the intrinsic value of learning.

The flipside of resisting grade-consciousness is fostering a sense for the intrinsic value of education. Teachers should regularly highlight the actual importance of what the students are learning. How does this course help them understand reality, develop vital intellectual skills, and appreciate the world in which they live? Teachers should call those things out and be in awe of them in front of students. “What did you learn from E.E. Cummings’s poem ‘In Just—’ about what it means to grow up, students? That is of inestimable value. No grade in this course means anything compared to the understanding that the ‘goat-footed / balloonMan’ has called to us all. He called to your mother and father, your uncles and aunts, and everyone you know. All of us at one time came ‘running from marbles and / piracies’ or ‘dancing / from hop-scotch and jump-rope.’ That is a part of what it means to be human.”

4. Use competitions, contests, and other forms of recognition in place of grades for external motivation.

Intrinsic motivation is the purest motivation to learn — the self-driven pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness. But healthy competition is also a part of the human condition. It has an appropriate role to play in the context of education. Without any other outlet for competition, though, students will default to grades and GPAs to fill that role. A school can resist this by introducing narrower competitions, contests, and other forms of recognition. Consider an annual math contest, creative writing prize, or quiz bowl. Display excellent science projects, papers, or works of art. A wide variety of such recognition gives everyone another way to think about excellence. It also affords students who may excel in one area but not others the opportunity to be properly recognized for their contribution to the community.

5. Be upfront about grading criteria (both quantifiable and non-quantifiable).

Resisting grade-consciousness does not mean a teacher should be cagy about expectations. There is information students should know when they are done with a course. There are skills they should possess. And there are intellectual habits of mind that any good school is trying to foster. Students should be aware of this, know what is expected of them, and understand how to meet those expectations. These expectations are best expressed in concrete terms, though, not in abstract numbers. Just as students need to ask the right questions about performance, teachers should make the right kinds of comments. Teachers should replace comments like, “You have to get 93% or higher on this paper to get an A” with comments like “An excellent essay has a strong thesis, a compelling proof that demonstrates the case from the text, and a conclusion that shows real insight into the topic.”

6. Regularly take the temperature of students’ experience of grades, grading, and learning.

It is important to listen not only to parents but also to the students themselves. From time to time, school leaders and teachers should check in on the students to make sure they are experiencing leisure. Students should work hard. They should face challenges. They might even experience frustration. But, insofar as possible, schools should free them from the unrelenting, day-to-day experience of low-grade, slow-burn performance anxiety.

7. Limit access to grade portals or the scope of reporting that happens there.

If a school is blessed not to have adopted a so-called “grade portal,” it would be wise to resist doing so. Grade portals have proven to be one of the worst agents of grade consciousness. Both parents and students alike can become addicted to instant feedback, regularly checking for updates, and growing concerned if a teacher doesn’t post a grade in relatively short order. Grade portals also foster excessive concern over lower-order assignments. Getting a 3/10 on a homework assignment does not necessarily mean Johnny needs remedial help. He may have simply failed to grasp the concept immediately. The teacher and he may have already dealt with the misunderstanding. The situation needs no further attention. However, if Johnny’s father sees a 3/10 in a grade portal, he is going to be concerned. Now Johnny also has to face questions about his homework assignment at home. Maybe his parents will think they need to contact the teacher. Suddenly, every night’s homework assignment starts to feel like a test Johnny has to pass rather than practice for the next day. If a school has already adopted a grade portal and cannot get rid of it, they should consider a conversation with parents about the healthy use of grade portals. Policies might include:

- limiting parent access to specific times and seasons (perhaps more regularly early in the year, then switching to every two weeks);

- updating an aggregate “homework score” rather than reporting on each night’s work; or

- requiring teachers to report only major assignments or tests.

8. Focus grading on end-of-term results wherever possible.

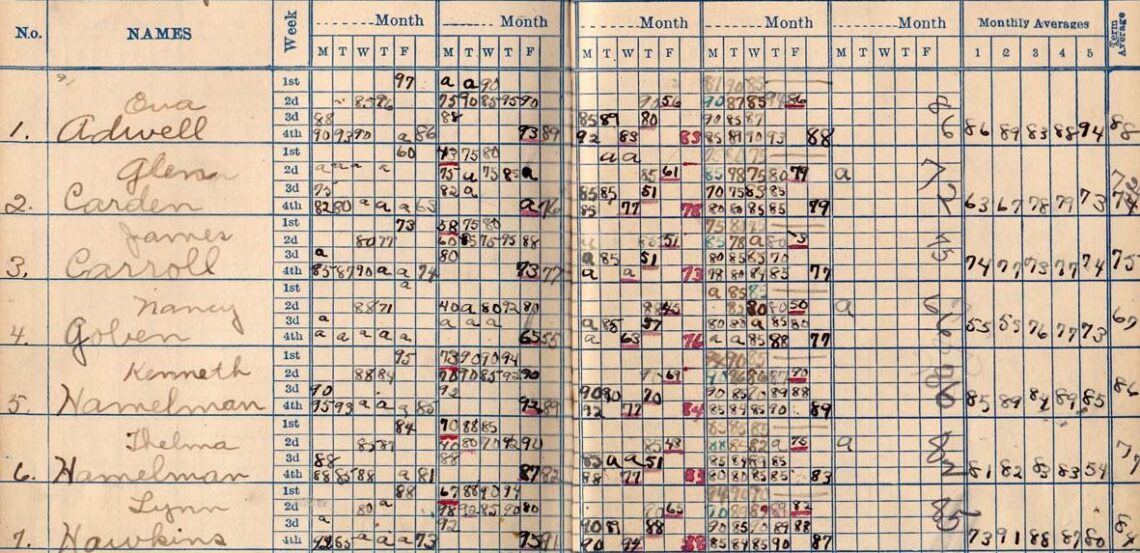

As long as she knows her times tables in December, does it matter that Anaya did not know them in October? A typical grading scheme sometimes punishes students for being slower learners. Imagine a scenario in which a student receives the following grades on a series of math tests: 73%, 69%, 88%, 97%. If a teacher merely averages these test scores to arrive at a final grade, the student would receive a B-. But what if that 97% on the last exam clearly and without a doubt indicates that the student has overcome every gap evident in the earlier two tests? Should the student receive a final grade on what she does know at the time the grade was assigned or based upon what she didn’t know earlier? Some ways in which a school might consider addressing this “reality gap” between a grade based on numerical averages and a grade based upon actual understanding include:

- placing a high value on end-of-term portfolios;

- using mastery-based testing wherever cumulative skills are being taught; and

- acknowledging the teacher’s objective and demonstrable judgment in the grading process (even if that judgment cannot be quantified).

Do you have any experiences to share or other thoughts on grades and grading? Join the conversation by leaving a comment below!

This article is part one of a four-part series on grades and grading.

- Part I: “The Industrial and Modernist Roots of Grading”

- “Part II: “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Assessment”

- Part III: “Rigor, Grades, Challenge, and Leisure”

- Part IV: “If Grade We Must”

Jon Balsbaugh is the founder and chief editor of Veritas Journal and owner and operator of Kairos Educational Consulting. Though his soul still imagines itself in the Pacific Northwest of his childhood, he now lives in South Bend, IN. He and his wife have five children. Mr. Balsbaugh has been involved in classical education for over twenty-five years. In addition to reading, writing, and thoughtful contemplation of ideas, he enjoys seeing the world through the lens of his three primary hobbies: fly fishing, foraging, and photography.

Header Image: “1923 Gradebook,” Cat Sidh (CC 2.0) (cropped)

One Comment

Gene Stowe

This is excellent, so far as it can go. I think the late point about evaluating what the student has learned at the end of the semester is critical — “averaging in” grades across the semester is horribly demotivating.

What may have been said before, and should be said, is that grades are a leading cause, if not the leading cause, of cheating. If a student goes for grades, they will at least be tempted to cheat. If they go for learning, they can expect to get just grades thrown in. One of my children in their first year of college had a professor who gave them their grade average every Friday as incentive. It did nothing but produce anxiety.

Grades are, on their own, misleading, meaningless, or both. Does the B mean an “A student” was slacking off or a “C student” was overperforming? Or something else?

Worst of all are the grading systems that compare students to each other instead of to a standard. My college roommate got 15% on organic chemistry, and it was a B. In those systems, students know who “killed the curve,”” and they enter into unhealthy competition, not the healthy competition described here.

Thank you for an excellent exposition.