by Jon Balsbaugh

We are now so used to the examination system that we hardly remember how very recent it is and how hotly it was opposed by some quite sincere people. Trollope (no fool) was utterly sceptical about its value: and I myself, tho’ a don, sometimes wonder how many of the useful, or even the great, men of the past wd. have survived it. It doesn’t test all qualities by any means: not even all qualities needed in an academic life. And anyway, what a small part of life that is.

— C.S. Lewis, “Letter to Lawrence Harwood (August 2nd, 1953)”

In the first and second parts of this series, I tried to make the case that grades could be eliminated from a classical school environment — and that they should be. At the same time, I recognize that it may be impossible for most schools to do away with grades. So in the fourth and final essay in the series, I will present a few ways a school might handle grades to reduce their negative impact on learning. Before doing so, however, I need to tackle one argument for grades that is popular in some classical school contexts, the argument that grades are essential to “rigor.”

There is some merit to the call for rigor, of course. We operate in a culture of falling standards, rampant grade inflation, and decreasing student resilience. On the one hand, the desire to maintain proper academic standards may be a reasonable response to a culture of mediocrity. On the other hand, even in our contemporary educational environment, it would be a mistake to accept without serious consideration that education should be rigorous. From there, the only question left would be how rigorous (a question which too often boils down to, “Just how hard should it be to get an A in this class?”)

Before accepting the value of rigor uncritically, it is worth attending to the terms of the discussion. Words matter.

Consider some of the definitions of “rigor” provided by Merriam-Webster:

rigor n.

-

- (a) harsh inflexibility in opinion, temper, or judgment (SEVERITY); (b) the quality of being unyielding or inflexible (STRICTNESS); (c) severity of life (AUSTERITY)

- a tremor caused by a chill

- a condition that makes life difficult, challenging, or uncomfortable

- strict precision (EXACTNESS)

- (RIGIDITY, STIFFNESS) “rigor mortis”

Do we really want classical education associated with severity, strictness, austerity, exactness, rigidity, and stiffness? Is that the path we must embrace if we want to push back against the “rising tide of mediocrity” in education? Fortunately, there is an alternative to “rigor” that doesn’t conjure up images of dead bodies. That word is “challenge.”

challenge n.

-

- a stimulating task or problem,

- a calling to account or into question

- an invitation to compete in a sport, b) a SUMMONS

- the act or process of provoking or testing physiological activity by exposure to a specific substance

A “challenging” education certainly involves discipline and strenuous activity. But there are higher values woven into the notion of challenge. Important matters are called to account. The problems placed in front of us are enlivening. A challenge is a summons to meaningful activity.

In Joseph Pieper’s masterpiece, Leisure: The Basis of Culture, he points out that scholē (the Greek word for leisure) is the origin of the Latin “scola,” the German “schule,” and the English “school.” In both a historical and philosophical sense, school arises from leisure.

This might conjure images of students sitting around on pillows playing educational games on their iPads; but leisure in Pieper’s sense is not laxity. In a 1998 introduction to Pieper’s book, Roger Scruton notes that leisure “is not the cessation of work, but work of another kind, work restored to its human meaning, as a celebration and a festival … We win through to leisure. ‘At the end of all our striving’ we rejoice in our being and offer thanks.”

The question, then, is not whether we work, but how we work and why.” The answer to that question is what distinguishes mere academic rigor from true intellectual challenge.

Academic rigor is marked by how many minutes of homework Justin has in third grade; intellectual challenge by whether he still loves to read and explore in his backyard.

Academic rigor is marked by how hard it is for students to get an “A” in Mr. Sanchez’s Algebra class; intellectual challenge by how engaged students are in discovering whether .9 repeating is really equal to 1.

Academic rigor is marked by the number of times Constance has to revise her essay on Locke’s Second Treatise of Civil Government; intellectual challenge by how interested she is in the truth of her thesis on the nature of private property.

An authentic, intellectually challenging education summons students to a difficult task, yes, but it also summons them to something real. Its arena is not the confined dimensions of a classroom or the fixed hours of a school day but the boundless world in which we live. True intellectual challenge is animated by the spirit of exploration; mere academic rigor by the specter of the grade.

Pieper makes a seeming side comment in Leisure that bears directly upon this question of grades:

[T]he distinction between the “servile” and “liberal” arts is related to the distinction between an “honorarium” and a “wage.” The liberal arts are “honored”; the servile arts are “paid in wages.” The concept of the honorarium implies a certain lack of equivalence between achievement and reward, that the service itself “really” cannot be rewarded. Wages, on the other hand (taken in their purest sense, in which they differ from the honorarium), mean payment for work as an article or commodity: the service can be “compensated” through the wage, there is a certain “equivalency.” But the honorarium means something beyond this: it contributes to one’s life-support, whereas a wage (again, in the strict sense) means the payment for the isolated accomplishment of the work, without regard for the life-support of the working person. It is characteristic, now, of the mind that has been formed by the “worker” ideal, to deny this distinction between honorarium and wage: there are only “wages.”

For many students, parents, and even some faculty, school is all about “wages.” Those wages are grades. The grades are deposited into a bank account. That bank account is a student’s grade point average. And the size of that account (always relative to others) is the currency that measures educational value. In more tragic cases, the GPA even becomes a distorted measure of personal value.

Of course, it may still be possible to excite some students who have been formed in the “worker ideal” with an engaging lecture, a good discussion, or an interesting demonstration. Ultimately, though, such students will consider the educational endeavor a failure without the compensation of a grade that they feel they deserve, that their parents find acceptable, and that will secure them a place in the college of their choice.

Quite a few years ago I was teaching an honors seminar to high school seniors that included a heavy writing component. I had just returned a set of marked essays when one of the students (we’ll call her “Cecilia”) stayed behind after class. Cecilia was one of the strongest students in the class. She was an excellent writer and a very hard worker. If anything, she worked a little too hard. The essay was also very good, an A- if I remember correctly. But I could tell Cecilia was rattled and out of sorts.

“I need to rewrite my essay,” she said. She wanted to meet with me after school to go over it.

It was my policy to allow students to revise or rewrite any paper they wanted to, though I recommended they run their ideas for revision by me first. I was also always happy to meet with students after school. In this case, though, there was little Cecilia could do to improve the essay that wouldn’t involve a re-reading of the text, a lot of time and effort, and substantial revision. It was also possible that she wouldn’t see much return for her effort. I recommended that she skip this rewrite and that she and I have a conversation ahead of the next essay instead. But I added the question, “Why do you want to rewrite it anyway?”

“I have to get an A+ in this class,” she said. It was college application season. She was putting herself under a tremendous amount of pressure. And she was aware that an A+ in an honors course earned a bonus towards a higher GPA.

I told Cecilia that I would take her revision if she submitted it, but that I could not help her get an A+. That wasn’t how learning worked.

“I am a teacher,” I said, as kindly as possible. “You are an excellent student already. The results of that will take care of themselves. But I am not going to participate in the process of you seeking a higher grade only for the grade’s sake. On the other hand, if you decide you want to become a better writer, I will give you all the time and attention I have.”

Cecilia was both frustrated and shaken by it. In the moment, she did not want to become a better writer. To her credit, she had the integrity to say so. She wanted a higher grade. That was it. So we parted without making an appointment.

Several days later, Cecilia approached me again. After giving it considerable thought, she decided she really did want to be a better writer. It is a noble aim to write well — one that requires effort, discipline, and, above all else, humility. I could read a readiness for all three in her demeanor. At least concerning writing, and at least for this moment, Cecilia’s disposition had fundamentally changed.

Some may find this approach harsh. It is definitely not an approach to take with everyone, and a teacher has to depend upon prudential judgment given the student in front of him. But as long as we allow students like Cecilia to enslave themselves to a servile “worker ideal,” the highest aims of the classical education movement will remain unattained. We will not have “schools” marked by leisure in the old, high sense. We will have credential factories that are little better than the ones down the street.

The next and final article in this series will take up the practical question facing most administrators and teachers. “Even if we can’t get rid of grades entirely, how can we help ourselves, our students, and our children embrace the way of true leisure in their learning?”

This article is part one of a four-part series on grades and grading.

- Part I: “The Industrial and Modernist Roots of Grading”

- “Part II: “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Assessment”

- Part III: “Rigor, Grades, Challenge, and Leisure”

- Part IV: “If Grade We Must”

Jon Balsbaugh is the founder and chief editor of Veritas Journal and owner and operator of Kairos Educational Consulting. Though his soul still imagines itself in the Pacific Northwest of his childhood, he now lives in South Bend, IN. He and his wife have five children. Mr. Balsbaugh has been involved in classical education for over twenty-five years. In addition to reading, writing, and thoughtful contemplation of ideas, he enjoys seeing the world through the lens of his three primary hobbies: fly fishing, foraging, and photography.

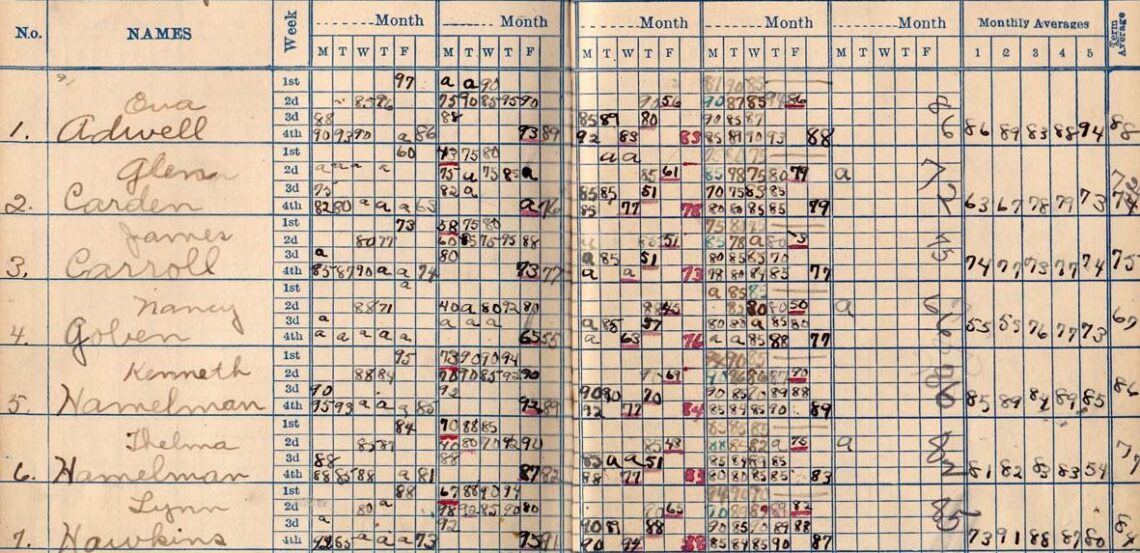

Header Image: “1923 Gradebook,” Cat Sidh (CC 2.0) (cropped)