by Jon Balsbaugh

When technique enters into every area of life, including the human, it ceases to be external to man and becomes his very substance. It is no longer face-to-face with man but is integrated with him, and it progressively absorbs him…This transformation, so obvious in modern society, is the result of the fact that technique has become autonomous.

– Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society

Grading. It is one of the many rituals of an educator’s life.

Sometime after the current term, teachers all over the world will find themselves sitting down with a cup of coffee to mark up final papers, tally end-of-term exams, and take a final look at student portfolios. When they are done scoring the work, most teachers will rely upon an online grade book or spreadsheet to generate a number like 82.7%. This number will then translate to one of five letters (sometimes followed by a + or – sign) — the grade. That grade will go into a schoolwide database with other teacher’s grades where it will be converted back into a number — the student’s “GPA.”

Most of the computerized programs that handle this work will be statistically significant down to a hundredth of a point. If the program figures 79.94%, the student will receive a C+. If it calculates to 79.96%, the program will round up and the student will receive a B-. The system is clear. It’s quantitative. It’s reassuring in the way data often is. This is how it works … as long as no one second-guesses the system. However, at this point, the system needs to be second-guessed.

It is especially important for classical schools (whether public or private) to question the conventional wisdom around grades. From its inception, the contemporary movement to restore “classical” education has been a movement of reform. It was born with a skeptical eye towards modernist educational methods and “school as usual.” So in classical education circles, we have to start by asking, “Did Socrates ever have to decide to give Plato an A or A-? Would Plato ever have given an early draft of one of Aristotle’s essays on ethics a 93%? Did a young Tommaso d’Aquino ever have to appeal to Albertus Magnus to overturn a B+? The answer to all of these is an obvious, “No.”

Of course, just because a practice is new does not mean it is bad. We can be grateful for modern dentistry, running water, and the written word — all of which people got along fine without at some point in human history. But as grades are not a part of the classical, humanist, liberal tradition, we should at least ask why they were invented and by whom, what they were for, and how they affect the essence of education. We have to begin by recognizing that grades, like multiple-choice questions, learning styles, standardized testing, and many other trappings of school-as-usual, are a function of an industrialized, modernist approach to society.

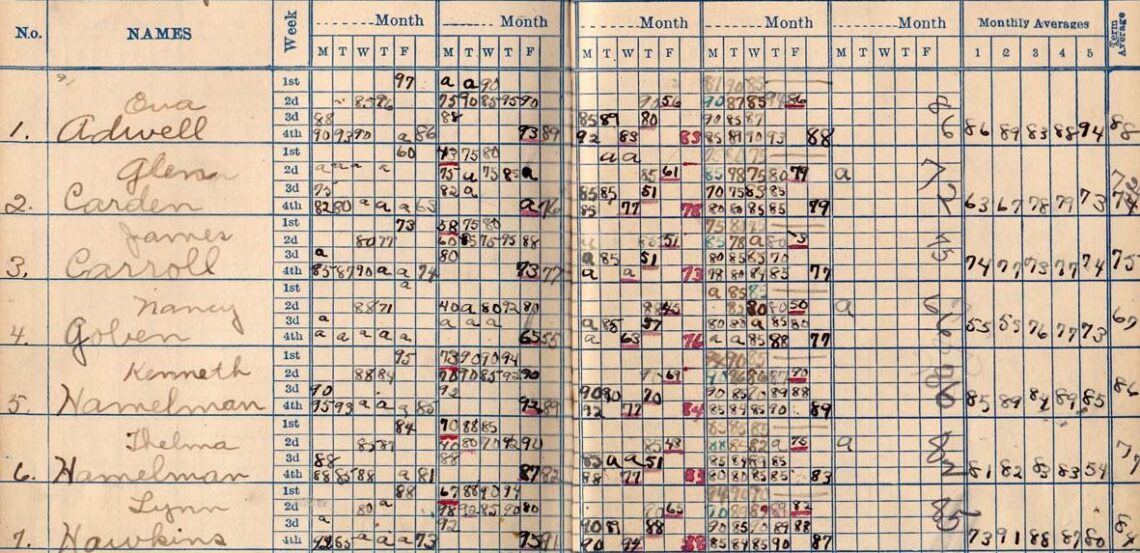

Yale president Ezra Stiles was probably the first to introduce fixed “grades” when he added the designations “Optimi,” “Second Optimi,” “Inferiores,” and “Perjores” to Yale’s exit exam in 1785. In doing so, Stiles transformed that exam from what we would call a “pass-fail” experience into something different. Education was now about something beyond freedom, practical empowerment, or contemplation. Being well-schooled became a discrete skill unto itself, producing a terminal outcome that could be ranked relative to others who were being schooled.

At first, some expressed concern that such a system might introduce inappropriate levels of competition and distract students from the intrinsic value of learning. Even Horace Mann, the so-called “Father of American Education,” cautioned in 1846:

“If superior rank … be the object, then, as soon as that superiority is obtained, the spring of desire and of effort for that occasion relaxes. The pupil knows that the record, ‘perfect,’ set against his name, will stand, whatever fading-out of the lesson there may be from his mind. He dismisses, therefore, all thought of the last lesson, and concentrates his energies upon the next; and this becomes his history from day to day.”

Despite such warnings, other schools soon followed Yale’s example. Compulsory education and the modern taste for efficiency would lead to greater and greater standardization. By the mid-20th century, the A-F grading system, 4.0 scale, and grading with percentages were firmly ensconced in our collective understanding. Since then, the professionalization of the teaching industry has increased the granularity of grading by trading in daily exit tickets, nationally normed exams, educational rubrics, and the like. Finally, over the past several decades, increased competition in the college admissions game has caused a sharp uptick in parent and student anxiety; and the education industry has responded by meeting the increased demand for instantaneous, up-to-date, real-time “grade portal” access.

It would be one thing if grades, grading, and all the modern apparatus supporting them provided some measurable goods. However, as Jessica Lahey, author of The Gift of Failure, wrote of our current situation:

While there’s limited evidence on the benefit of grading portals on academic achievement, there is plenty of research to show that extrinsic motivators, such as grades, as well as parental surveillance and control, are detrimental to kids’ long-term motivation to learn and undermine their relationships with teachers.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, grades appear to have even less value than they once did. A recent study out of the American Institutes for Research found: “It is possible—even likely—that shifting grading standards give parents, guardians, and students a confusing or inaccurate picture of what students know and can do, especially considering pandemic-related learning losses.” Grade inflation has created a significant discrepancy between what parents believe about their children’s performance in school and what test results suggest they actually know and understand.

Perhaps the only positive educational outcome of the pandemic was that it forced everyone to ask new and challenging questions about “school as usual,” questions like, “What does this grade mean?” In this context, even mainstream educators, colleges and universities, and others are beginning to question the value and viability of our grading system.

Any number of times in my career, I have seen very good students beat themselves up over an A-, young men or women who had once been committed to the pursuit of truth lose their love of learning because of a grade, or tensions build between the family and the school over grade appeals or college admissions. If grades are historically unnecessary, increasingly misrepresent reality, and interfere with our highest intellectual aims, then those of us in the classical movement should at least join in questioning their place in the future of education.

This article is part one of a four-part series on grades and grading.

- Part I: “The Industrial and Modernist Roots of Grading”

- “Part II: “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Assessment”

- Part III: “Rigor, Grades, Challenge, and Leisure”

- Part IV: “If Grade We Must”

Jon Balsbaugh is the founder and chief editor of Veritas Journal and owner and operator of Kairos Educational Consulting. He lives in South Bend, IN with his wife and five children. Mr. Balsbaugh has been involved in classical education for over twenty-five years. He enjoys seeing the world through the lens of his three primary hobbies: fly fishing, foraging, and photography.

Header Image: “1923 Gradebook,” Cat Sidh (CC 2.0) (cropped)

3 Comments

Sadie Adderley

If only one change could be made to modern education the abolition of grades should be it. It wouldn’t solve all the current problems, but it sure would go a long way.

I’m constantly amazed that so few members of the classical schools movement understand how detrimental grades are to true education.

selfie_journal_bhOr

Селфи Журнал: новинки в эстетической медицине и косметологии

selfiejournal

GK_Peresvet_nuPa

GK Peresvet: консультации по выбору винтовых свай бесплатно

Сваи Пересвет: винтовые сваи купить в Москве и Московской области