by Andrew Gaylord

I would hate to relegate beautiful things to the realm of merely pleasurable things. Therefore I think it is important to regularly pursue experiences of the beautiful that do not initially appear to be pleasurable at all. With regard to music this means taking the regular opportunity to listen to music that is not easy. Listening to Robert Johnson’s brief catalog or to Arnold Schoenberg’s String Quartet No. 1 are both great places to start.

Let’s face it: with the ease of access to any and all music today, most of us find ourselves listening to music at extended intervals throughout the day. And what kind of music do we most often choose? Easy listening. Music that we know. Or, at least, music that we know will not challenge us too much—we are trying to get things done, after all. We listen to music while we are cooking, while we are doing our homework, while we read the newspaper, while we play games with family and friends at the end of the day or throughout the day on weekends. We do not plan to listen closely to the music, and we do not want the music to distract us from what we are really doing. In this way, music operates as a lubricant for smoothing out the activities of our day, as engine oil lubricates the many parts of a car’s engine so that it will continue to run well. We use music to provide an underlying, pleasurable environment. If this were the only way we listened to music, this would be a tragedy indeed.

By listening to a piece of music that challenges our ears and our sensibilities we open ourselves up to new experiences of beauty, and by engaging with those pieces we gain practice in not only engaging with beauty but also seeing it in the world around us. Artists are the professional spotters of beauty, those who have dedicated their lives to hunting it down and pointing it out to the rest of the world.

New, unfamiliar art is a struggle, most often because we do not understand the world in which it was created. We live in bubbles which sound a certain way. Music from other bubbles is not going to sound like music from our bubble. But to really pursue beauty means we need to leave our securely beautiful spaces, because beauty permeates all spaces. If you do a bit of legwork to understand what life is like in other spaces, the music will become more engageable. Not much is required. If you listen in an engaged way, this other world will unfold for you. And the great point of pleasure in listening to unfamiliar, challenging music comes when you recognize that you can actually imagine yourself in other bubbles. You could have been born elsewhere. This is a powerful moment of human connectivity that art can enable between people from dramatically different walks of life. With grace and close listening, maybe the bubbles will pop, and we will see that we are in fact living together in the same world. The so-called masterpieces of any tradition are excellent for bringing about moments like this. (It is edifying in itself to recognize just how many masterpieces are out there). For as much as a masterpiece may reflect its specific historical and cultural situation, these pieces of music are packed with elements of human life that anyone can grab onto, loaded with reflections of universal human truths.

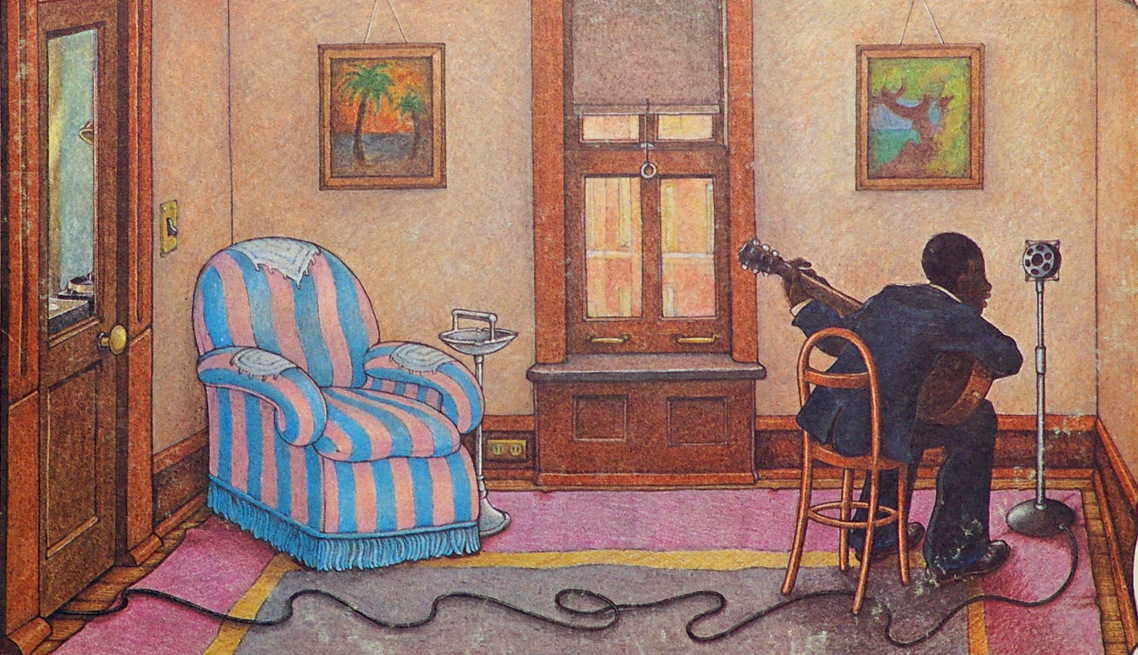

The recordings of Robert Johnson are few in number. Recorded in the late 1930’s on crude devices, their audio quality is far inferior to what we are accustomed to today. Johnson’s voice is highly inconsistent, sometimes shrill, sometimes gravelly. It is not easy listening. His songs are simple and repetitive in their structure. But all of these qualities are superficial. His simple song structures allow for infinite variations of tone and color both in his voice and in the guitar. The simple structure allows him to tell a gripping story, to bring the story to life with subtle changes in the melody, in dynamics and in tempo. His voice is ever-changing to fit the character of the lyrics and the needs of the story being told. Once you have committed to the world of this music, his voice strikes an eternal bardlike quality. He could be a storyteller in any age. He could be singing in any language. His fluctuation in tone from bright arrogance to fragile vulnerability paints the spectrum of human attempts to chase beauty down and capture it.

The story of Robert Johnson goes that he met the devil at the crossroads and sold his soul for the gift of music. Whether or not he invented the story himself, Johnson did not go out of his way to debunk it. This story was used by his detractors to keep people away from his music. They labeled his music as dangerous, since it contained songs about bad behavior. At the very least this “origin story” highlights the complexity of the music. Johnson was a master craftsman. And you can hear in his music a man who was committed to exploring and expressing musically the full range of human experience, from the depths of grief to the heights of ecstasy. Once you have entered the world of his music, you will come to find that it is exquisite in design, perfect in its delivery and dazzlingly intricate.

A completely different listening experience is spending 45 minutes with Arnold Schoenberg’s String Quartet No 1. I have long struggled with Schoenberg. Bits and pieces of his music have, throughout my life, given me great pleasure, but I have never had a clear sense of the man as an artist. He is intimidating. His 12-tone technique of composing appears to many people too mechanical and overly complex. So many notes! And why is it so challenging to access the humanity in the music? This is not a problem with the music, I have found, but with myself.

I recently watched a video of the pianist Glenn Gould explaining why he thought Schoenberg was the greatest composer of the 20th century, and I was intrigued. I picked up a book of his essays entitled Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg, and I was captivated by his expansive and humane way of thinking about music. Schoenberg had a long career before 12-tone. He was a teacher. He was deeply rooted in music history. In fact, Schoenberg saw his 12-tone technique as squarely in line with developments of the great composers before him, from Brahms to Beethoven to Bach. When I first heard his String Quartet No. 1, my first response was a sort of fear that I have experienced before when listening to his music, namely, “This is going to be out of my reach, cold, unfamiliar.” But it wasn’t. Like the best stories, I never knew what was about to happen, but I found myself continually excited by the next surprise around the corner and moved by the pictures flowing from the music. Familiar pictures presented themselves to me in a wholly new way. It is a vast musical tale. I found myself feeling emotions in myself that I could not name. And if I tried too hard to name them, I would find myself smiling at how the story had changed. Phrases familiar and strange led into phrases more familiar and more strange, sometimes more complex, oftentimes more simple. I found myself snatched up by this music, led by my hand, so to speak, and introduced to a family of characters. The phrases resonated with me deeply, as good fictional characters do with their familiar trials and transformations. This was not background music. In fact, committing to the music, working on listening to it, made up the entire difference between my idea of the music and my experience of it.

Both Schoenberg and Johnson are out-of-the-way music. They don’t pop up often on the radio or in Spotify playlists because they have a low listenability threshold. Work is required to make them listenable. That is what keeps people away from a vast sea of beautiful music. How many opportunities for a whole new, deeper appreciation of beauty have we passed up because work was required? There is a great deal to do, after all. Imagine how an early nineteenth-century listener might have listened to a Beethoven symphony only once in his or her lifetime, and yet it could guide his or her soul into a profound new mode. We, on the other hand, have all of the works of Beethoven as well as every work of every major composer, songwriter, and instrumentalist at our fingertips at all times. Sometimes it feels like too much to bear. Once we get past the fact that it is not possible to engage with every beautiful thing, we can make a start. One great piece of music may be all we really need, assuming it always keeps us working.

Arnold Schoenberg, String Quartet No. 1 in D-minor – Op. 7

Robert Johnson, Complete Recordings

Andrew lives in Minneapolis, MN with Ruth, his wife, and his two children, Henry (3) and Gwenyth (1). He teaches Music, Art History and Literature and Composition to 7-12th graders at Trinity School at River Ridge in Eagan, MN.

Header Image: Album Cover for King of the Delta Blues Singers, Vol II, 1970 (used in keeping with Fair Use)

One Comment

Richard Kamins

While I agree with everything you write about stepping out of our “bubble” and listening to challenging music, music that not only changes the parameters of our musical life but also pushes to understand how music moves us.

One error in the essay––Robert Johnson first recorded in 1936 and in 1937 but never that we know of in the 1920s.

Thank you,

Richard