It’s January again, which means thousands of books, films and other copyrighted items entered the public domain and are now free to be appreciated, reprinted or artistically remixed.

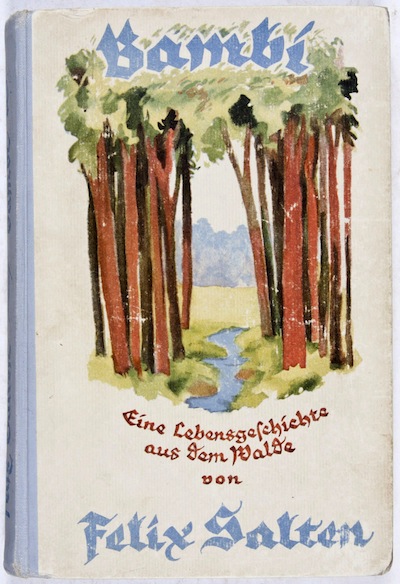

Among the notable works to enter the public domain this year are two classic children’s tales, A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh and Bambi, A Life in the Woods by Felix Salten. Both of these works demonstrate the great capacity for moral seriousness in so-called “children’s literature.”

With its simplicity, wit, and just enough air of nostalgia, Winnie-the-Pooh has inspired countless films (including two back to back in 2017 and 2018), a 1970 Billboard hit by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and considerable philosophical reflection — most notably Benjamin Hoff’s wildly popular The Tao of Pooh. Its translation into Latin even made Winnie Ille Pu the only book in that language to top the New York Times best seller list. Similar to The Little Prince and Tove Jansson’s Moomin books, one appeal of the Pooh books to the adult reader are the poignant aphorisms and observations that are full of wisdom and truth beyond their utterance:

The Old Grey Donkey, Eeyore, stood by himself in a thistly corner of the forest, his front feet well apart, his head on one side, and thought about things. Sometimes he thought sadly to himself, “Why?” and sometimes he thought, “Wherefore?” and sometimes he thought, “Inasmuch as which?” — and sometimes he didn’t quite know what he was thinking about.

You can’t be in London for long without going to the Zoo. There are some people who begin the Zoo at the beginning, called WAYIN, and walk as quickly as they can past every cage until they get to the one called WAYOUT, but the nicest people go straight to the animal they love the most, and stay there.

You can’t stay in your corner of the Forest waiting for others to come to you. You have to go to them sometimes.

As with Winnie-the-Pooh, there is more to Bambi than a simple children’s story. But Bambi has a mature wisdom of an different kind. Popularized by the 1942 Disney film, the character of Bambi is well known. The book, however, is less so. And it differs considerably from Disney’s adaptation. Though the film was received as a cautionary environmental tale with anti-hunting themes, Salten was himself a hunter. Furthermore, the book was intended as a coming-of-age story oriented more towards adults than children. One entire chapter is devoted to a discussion between two leaves about the inevitability and nature of death. The book is beautifully written, though, with themes reminiscent of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Here is a longer passage that illustrates the melancholy of the original text:

“What’s that,” Bambi enquired, “the dead leaves from last year?”

“Come and sit beside me,” said his mother. “I’ll tell you all about it.” Bambi gladly went and sat beside her and snuggled in close while she explained to him that the trees do not stay green all the time, that the sunshine and the lovely warmth go away. Then it gets cold, the leaves turn yellow because of the frost, they go brown and red and, one by one, they fall off the trees so that they and the bushes reach their naked branches to the sky and look completely forlorn. But the dead leaves lie on the ground, and when they’re disturbed by somebody’s foot they rustle: There’s someone coming! Oh they’re very good, these dead leaves from last year. They do us a good service by being so eager and by keeping watch the way they do. And now, in the middle of summer, there are still lots of them hidden under the things growing on the ground and they warn about any danger long before it gets near.

Bambi pressed close against his mother. He forgot all about the meadow. It was so cosy to sit here and listen to what his mother told him.

Then, when his mother stopped speaking, he thought about what she had said. He thought it was very nice of the good, old leaves to watch over them so carefully even though they were dead and had been frozen and had gone through so many things already. He tried to think what that danger, that his mother kept talking about, could actually be. But all that thinking tired him out; it was all quiet around him, all you could hear was the heat of the air. And he went to sleep.

Such a passage is all the more haunting when one knows that Felix Salten was an Austrian Jew, the grandson of an Orthodox rabbi. While it does not appear that Salten himself ever interpreted the book for the public, many have found an anti-fascist allegory in Bambi. The book was banned and publicly burned in Germany in 1936 for this reputation.

Also included in this year’s set of books to come into the public domain are Langston Hughes’ collection of poetry The Weary Blues, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, T.E. Lawrence’s The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (the basis for Lawrence of Arabia), H.L. Mencken’s Notes on Democracy, and William Faulkner’s first novel, Soldier’s Pay.

New films whose copyrights are expiring include the docufiction Moana; Rudolph Valentino’s final movie, Son of the Sheik; and the German expressionist film version of Faust by F. W. Murnau.

For a very deep dive into what’s now available or to get a sneak peek at next year’s public domain releases, visit the University of Pennsylvania’s Online Books Page or Duke University’s Center for the Study of Public Domain.