by Abbey von Gohren

Our rental car dove in and out of the late evening pools of shadow as we drove through the St. Ynez Valley just inland of California’s central coast. In a landscape layered with place names in Spanish (and indigenous names guessed at in Spanish long ago), there was one town on the map that stuck out: Solvang. Sounds like a place in Minnesota or Wisconsin, I mused aloud. Signs told us that this was a “charming Danish village,” but we must have hit it on the wrong day in the wrong mood, because all I remember from our visit is overly-sweet pastries, mediocre coffee, endless gift shops, and suffocating heat. After barely an hour, we made the decision to head toward the coastal breezes again.

I scrolled through the town website on my phone, trying to find out what the big deal was with this place we’d just hightailed it out of, when I finally found some history. Settled by Danish immigrants, and followers of N.F.S. Grundtvig, “founder of the folk school movement” it said. Hm. Not exactly a household name. Still, there was certainly a whiff of the familiar about him.

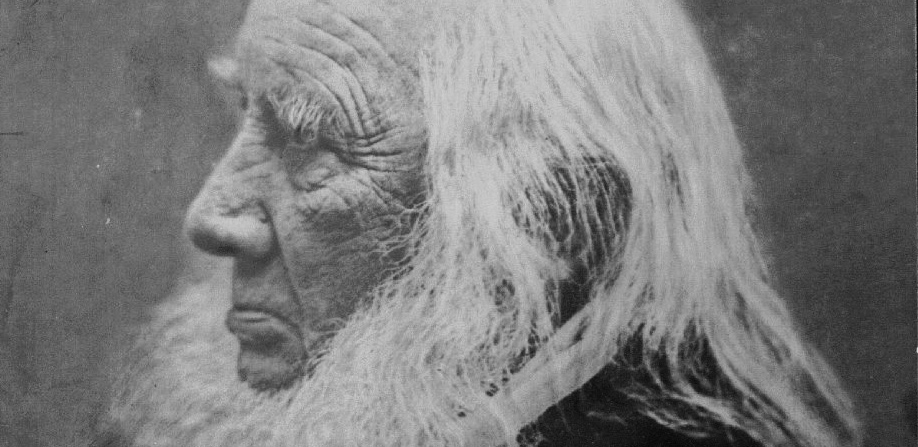

Nicolai Frederick Severin Grundtvig (1783-1872) was born in the small Danish village of Udby, but spent much of his life in bustling Copenhagen. His life overlapped with that of his more well-known fellow Danes, Soren Kierkegaard and Hans Christian Andersen. Like these men, N.F.S. Grundtvig simply defies categories. Committed Lutheran pastor, lifelong philosopher and historian, sharp polemicist, active politician, prolific hymn-writer, poet, researcher of all things Norse and mythological—the list of his passions goes on. Over a third of the hymns in the Danish Lutheran hymnody are his.

Politically, he was an absolute monarchist and yet he saw the arrival of democracy in his time as inevitable, fully welcoming its implications for the human person in terms of freedom. In a country that had only recently liberated its serfs, he saw education as important for all classes of people, especially the peasantry. And what Grundtvig meant by education is perhaps his most significant and lasting contribution to the world.

“First man, and then Christian.”

This phrase is one of Grundtvig’s most frequently-quoted, and expresses well the nuance in his thought which manages to remain robustly Christian and unapologetically humanist all at once. It originally comes from one of his poems:

Human comes first and Christian next, this is a major precept;

Our Christianity comes free, a gladness pure and perfect,

but gladness only in the end for those who truly are God’s friend

and Truth’s right noble kindred!

They who would truly human be while on this earth still living

lending an ear to Truth’s own word, to God the glory giving;

If Christian faith is the true way,

though ‘Christian’ they be not today they will be so tomorrow!

#123, Living Wellsprings: The Hymns, Songs, and Poems of NFS Grundtvig

To Grundtvig, the particulars of our own culture are the stuff of who we are. We must love these things, study them, cherish them. Whether you are Danish or Tanzanian, you must learn the traditional dances, cook the food, retell the myths. It is only to a heart and mind and body that is freely expressed in its own time and place that something as universal and cross-cultural as Christianity can come and find a home. Christianity is not abstract for him—the incarnation was concrete and real, and God’s people have always been in the specific. He says: “man is “spirit and clay…the word of Scripture coincides with the heart’s own story.” For him, Danishness matters – literally, it is the stuff of which a Danish Christian is made.

Where are you from? I am a girl from Minnetonka, a suburb of Minneapolis, Minnesota, with mostly Norwegian immigrant farmer ancestors who forged their way to the new world. This is my starting place. What, then, is the overarching quality that I hold in common with you, even if we do not (yet) profess Christian faith? Grundtvig proposes mystery:

Be he Christian or heathen, Turk or Jew, every man who is aware of the spiritual nature in himself is such a glorious mystery that he casts absolutely nothing aside merely because it is strange and seems as inexplicable as himself. On the contrary, he is almost irresistibly drawn to what is strange, because at heart it resembles him, and because in it he expects to find the answer to his own mystery, an answer he can’t possibly expect from something he can see through in a trice. Therefore such a person, whether in fact he is of this, or that, or no faith in the Godhead, never finds himself attracted to transparently “enlightened” people whose whole wisdom can be learned by heart in an hour—and possibly even explained to clever dogs! Rather he is attracted by the mysterious, deep natures that sense more than they see, feel more deeply than they can fathom, and speak with far greater spirit than they are aware of.

Nordic Mythology

For the mystery of a human being cannot be explained quickly, in rote fashion. Rather, free persons are ineffably attracted to one another, and join together in “sensing more than they can see, feel more deeply than they can fathom, and speak with greater spirit than they are aware of.”

“School for Life”

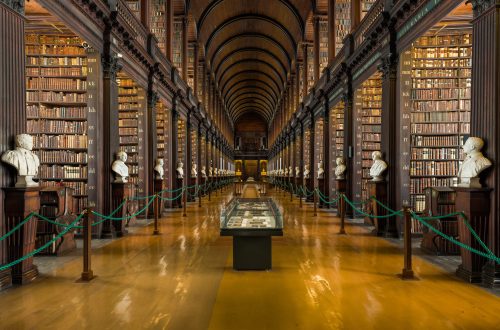

When Grundtvig looked around Denmark in the 1800s, he saw miserable young boys being forced to go to school, drilled in Latin forms instead of speaking their native Danish, and made to read stories about the glories of Rome while left in the dark about their own Nordic myths. He denounced this system as the “School for Death.” What he proposed as an alternative was the “School for Life,” a sprawling plan which he developed throughout his life. He always remained true to the following: learning ought not be compulsory, it should be rooted in the traditions of a people, it trains the whole person, and it accomplishes these aims through oral culture (singing, storytelling, poetry), and hands-on learning primarily, over and above written culture.

It was actually his view on how God comes to be present with his people that led him to prefer oral culture for learning, something he called his “matchless discovery.” For him, the Church, as it was expressed vocally in the sacraments, came before written scripture. The Word is primarily spoken, which initiates reality: “only in the congregation is heard the word which creates what it names, the living Word, Jesus Christ himself…The Word has here again become drama and myth, not judgments of reason or moral precepts or edifying observations, no—the Word is the bond between heaven and earth.” Grundtvig was convinced that as people of all ages, from little ones all the way up to the elders, came together in the “School for Life” to share in the Living Word, a true love of learning would take root and bind them together.

Grundtvig’s folk schools are not only still in existence, they are thriving, and experiencing a fresh wave of interest as people seek to find meaning in learning again. In my home state of Minnesota alone, about 20 new folk schools have been founded within the last five years, the acclaimed North House Folk School in Grand Marais on the shores of Lake Superior being one of them. These centers for culture-learning take many different expressions. In the north woods, for example, birchbark canoe construction, pine needle basket weaving, welding, lathing and other hands-on skills are at the fore. Other places focus on farming in harmony with nature. Still others focus on ancestral Norwegian or Swedish skills, like rosemaling or genealogical research. Many of them call for living on-site for weeks or even months at a time. What they hold in common is what was central to Grundtvig’s vision: no exams, freely chosen, rooted in traditions of time and place, love in action, and living and learning in community.

We go then to books not as bookworms who will feed on them as we would feed on corpses and carcasses, but as living people who wish to learn from books what we cannot tell ourselves—namely, how human life manifested itself in days gone by, what obstacles it met, how it overcame them, and what we can deduce from this about the nature and character of human life as well as the best way of developing and making use of it.

If we thus consider all books as being contributions to the history of human life—in the whole human family, in the different cultures, and in the individual—we can see emerging a quite different kind of learning from the deadly pedantry we must renounce in our school as the work of “frost-giants.” This different kind of learning not only extends to all that is knowable, but embraces is as a living idea and with a common purpose, which is the enlightenment of human life in all its directions and relationships.

School for Life: NFS Grundtvig on Education for the People

For Grundtvig, to be human is to be a member in the School for Life—we all, by definition, have a sense of wonder which propels us. It is true that it may have been inactive, deadened by the chilly effect of the pedantry of our time—slavery to the grade point average, the exaltation of exams, input-output models of education, schools as business ventures for technology firms, etc. In contrast, this man lifts up a remarkable vision of learning together that is robust, joyful, and fully alive—one which brought renewal to his country in his time and may very well bring life to us.

Abbey von Gohren is from Minneapolis, Minnesota. She connects with her Norwegian heritage by eating lots of potatoes, digging through ancestral archives at the History Center, and practicing friluftsliv (free air life), which means walking, eating, reading, sleeping and breathing outside whenever possible. Yes, even through the legendary winters.

One Comment

Henry Lewis

Learning to learn again! This is such a wonderful reflection on the nature of true knowing. How do we nurture an atmosphere of learning? How do we keep the fire and hunger to know alive? Oh, I am excited to muse a good long time on this – and then apply it to my own wanderings. Thanks for the writing.