by Renée D. Roden

In the world, but not of it.

How does a Christian relate to the world? We are, indeed, in the world. And we are of it, just as we attach a geographical marker to our Savior of Nazareth, so each of us is signed with our own “ofs” and “froms.”

What good can come from Nazareth?

What is the good of an incarnational God? Don’t we idolize the ability to transcend the pedestrian constraints of “time” and “place”? Eternal and omnipresent, omnipotent and boundless are the perennially defining characteristics of “deity,” because they are the necessary warrants for sacrificing our autonomy. The bargain of Divinity is that we worship what can operate in our lives with a power that transcends what limits us: a twenty-four-hour day and three miles of horizon.

What is the good of a God who is limited? What good, indeed, can come from our God being from Nazareth?

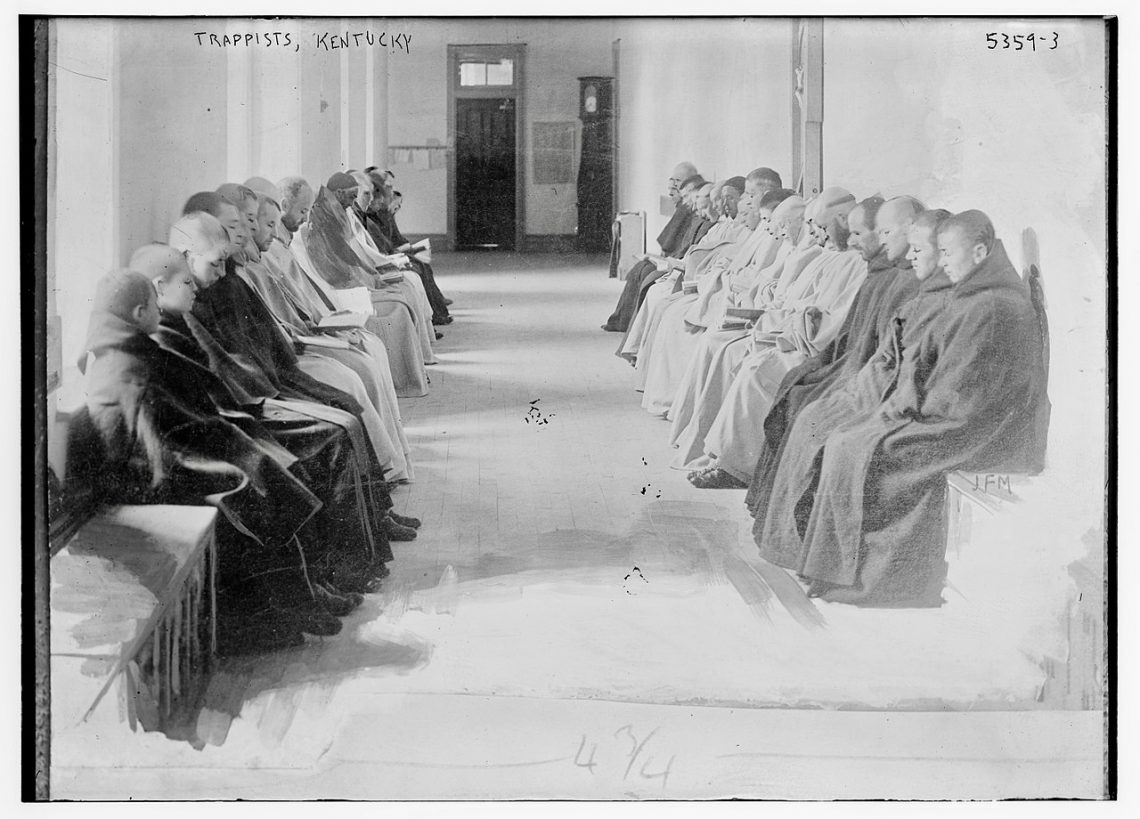

Thomas Merton, Cistercian monk and twentieth-century pop icon of the contemplative vocation with a celebrated affinity for the Dalai Lama, may seem like an unlikely source for an answer. Merton’s corpus is expansive, and includes many works of his own journals and interior musings. But his journey of self-understanding is most vulnerably and lucidly present in his bestselling spiritual memoir, The Seven Storey Mountain, which reveals a person who fundamentally saw himself through the lens of the places he inhabited. Merton, like Jesus, was a man who attached “of” to his name.

Merton is a contemplative not who forswore the world, but rather, approached his mysticism via the world. His most famous mystical revelation is fundamentally attached to a particular intersection: there is a plaque on the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville with Merton’s oft-quoted line about: “men and women shining like the sun.” The Seven Storey Mountain supports this argument that it is no accident or coincidence that Merton’s contemplation is so fundamentally attached to place. Rather, Merton’s contemplative approach to his Incarnate God occurred via and within the places he inhabited.

❧

One of the pleasures of living in a Literary City like Paris, London, or New York, is the truly quite sacramental delight of reading the description of a place while you are inhabiting a café chair, sipping on a cappuccino, or curled up in an attic apartment in that very place. Of course, it’s a pleasure that can be cheapened, flattened, attenuated to simply a thin shellac of glamour. There’s a cachet in story: these cities, painted in layers of human history, can be pawned for cultural capital. We sneer at the stereotype of the tourist who seems to chase these glamorous places but does not add her own story to them. Whatever has been deemed valuable or curious, the tourist must see, so that some of that value can rub, totem-like, off on her. In the tourist’s anxious desire to absorb as much as possible, he takes from these places—snapshots, stories, souvenir t-shirts, and cultural capital—but does not examine or encounter or give his own story to them.

Story makes a place valuable. Places that are truly cherished are thickly inhabited by the lives lived there during the past: the place becomes a spatial aggregate of its temporal history. A human instinct recognizes that it is somehow better—more valuable, more desirable, more notable—to live in a place where you have to wade through the past clinging to the sidewalks and apartment cornices than in the sort of soulless, place-less “airspace” that is the ascending aesthetic trend from California to Azerbaijan. We certainly need both air and space, but humans, even more deeply, need place.

❧

Biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann distinguishes between “place” and “space” in his seminal work on place in the Hebrew Bible, The Land. He defines “space” as an “arena of freedom without coercion or accountability, free of pressures and void of authority” and “place” as “space in which important words have been spoken that have established identity, defined vocation, and envisioned destiny.” Place is no longer simply a neutral environment. Place is a space inhabited thickly, in the context of a shared narrative, a covenant, a common identity arising from the community’s story of what has taken place on this soil, in the shared dirt.

Place is verifiably essential in the Old Testament, which is a story of God’s promise to God’s people for a specific place on the geographical map. But the story of the New Testament seems to be the story of God expanding God’s promise to all nations, all peoples, all places. When Paul says that there is no Greek or slave or free in Christ, does this not mean Christ also supersedes place? We often speak of Christ as the unifying principle, Christ as the one who overcomes all divisions and erases borders. Are places, then, of any consequence to those of us who have been baptized into the one Body of Christ?

Brueggemann responds: “Place is a decision to enter history with an identifiable people in an identifiable pilgrimage.” Our common pilgrimage of Church must begin in a place, for the story of redemption narrated in our Gospels begins also in a place: in a town of Galilee called Nazareth.

❧

The Seven Storey Mountain is a memoir fraught by place—by the desire to be and despair at being displaced, by the longing for a place, by the longing to transcend place. Although not quite a travel memoir, Merton’s account of his journey to God is certainly a spatial as well as spiritual odyssey. In Merton’s mind and in his writing, the spiritual is not divorced from the spatial. His spirituality is modulated by the space—or perhaps, rather, the place—which he inhabits.

A religious celebrity and a convert with massive cultural appeal, Merton, as a disputed and intriguing character of twentieth-century Catholicism, embodies modernity to a T. He is the saint for the age of the last self-help book, to borrow the diagnostic phrase of Walker Percy, Merton’s contemporary and fellow influential Postwar American Catholic. Despite his own dalliances and missteps, Merton demonstrates that prophetic holiness—the monastic single-hearted search for God, “quaerere deum”—can take place within this fissured, alienated modern self.

The Literary City is the secular cultural equivalent of Brueggemann’s sacramental, salvific place. The City holds the stories of the authors who have written there, who have lived there, who have worked out sentences while walking its cobblestones. Merton, child of the Literary City, discovers that just as the secular self can be the site of holiness, the Literary City, too, can be a sacramental place.

The Seven Storey Mountain seems an unlikely love letter to New York City. But the book, like Merton’s own mode of thought and existence, is deeply placed. The sections of Merton’s memoir are divided and modulated by place: his largely European childhood described as idyllic innocence is inseparable from the bucolic picturesques of medieval French villages; the decadence of his dissipate youth is intrinsically flavored with Cambridge’s meadows and cobbled streets. Merton’s spiritual maturation and awakening is structured as an inverse reditus–exodus to and from New York City. Merton enters the Literary City, and there matures so that he can exit that place for the sacramental place of the monastery.

In the crucial chapter that details Merton’s conversion, Part II: Bought with A Great Price, Merton narrates his budding friendship with the Hindu monastic Brahmachari. As he guides Brahmachari around Columbia University’s campus, Merton inquires about Brahmachari’s other university visits and asks a question one imagines is never far from Merton’s own mind:

“When we were coming out into the air at 116th Street, I asked him which one he liked best, and he told me that they were all the same to him: it had never occurred to him that one might have any special preference in such things.”

The impressionable Merton-the-student ponders this statement with supreme reverence. Merton-the-autobiographer comments:

“Surely by now it ought to have dawned on me that places did not especially matter. But no, I was very much attached to places, and had very definite likes and dislikes for localities as such, especially colleges, since I was always thinking of finding one that was altogether pleasant to live and teach in.”

Merton indicates his displeasure with himself for not being more detached from place, as Brahmachari was. Any desert father could tell you that, of course, holiness and happiness multiply the more detached the person is from material reality. Yet, they are called desert fathers. Their honorific title indicates a preference for place—a place which both symbolizes and is a place of radical detachment from the world.

Indeed, the climactic scene of The Seven Storey Mountain is centered around Merton’s experience of one particular place:

“It was a gay, clean church, with big plain windows and white columns and pilasters and a well-lighted, simple sanctuary. Its style was a trifle eclectic, but much less perverted with incongruities than the average Catholic church in America. It had a seventeenth-century, oratorian character about it, though with a sort of American colonial tinge of simplicity.”

Not only does Merton take an entire paragraph at the dramatic climax of his story to describe this place, but he describes it well. If you happen to visit Corpus Christi Roman Catholic Church on West 121st Street in Manhattan, sit in a pew in a back corner and open up to page two-hundred twenty-seven of The Seven Storey Mountain you will discover, as you read, how remarkably true Merton’s description rings. Merton has not simply described the church, he has it pegged, the way you can describe the contours of a best friend’s moods or the light of morning from your grandmother’s porch. It is the description that one can only write or think when one has deeply recognized what is described.

Merton’s search for a place that is “pleasant to teach in,” that is, a land “flowing with milk and honey” speaks less to his search for a place as merely a finely calibrated environment for flourishing than to his pilgrimage to find a place where, like Brueggemann writes, important words will be spoken. Merton’s hunger to find a place “pleasant to live in” is a biblical urge—a hunger and a thirst for the land promised by God, to be brought to the place where God will speak to him. A place where his pilgrimage—his quaerere deum—can be enacted.

❧

In a brief essay on Thomas Merton, “A Person that Nobody Knows,” published ten years after Merton’s death, Rowan Williams diagnoses Merton’s brand of personality as uniquely connected to place. Merton is an extraordinary figure, Williams suggests, because Merton’s character is completely modulated by his place. In the writings he transmits to us, Merton is “dramatically absorbed by every environment he finds himself in” (47). Merton admirably refrains from organizing or dominating his environment. Rather than seeking to exert the force of his own personality upon his surroundings, Merton receives from them the formation of grace. Merton is not a shaping mind, one that organized the world into his own grand system. Rather, Williams posits, in each place he went, Merton listened. Merton allowed himself to be shaped.

“Merton is sure enough of his real place, his real roots, to let some very strange and very strong winds blow over him, to let his understanding grow by this constant recreation in himself of other human possibilities” (47).

Merton listened for the voice of God present not just in the human heart—the whisperings of the human mind or the compunctions of conscience—Merton listened for God revealed in and throughout creation, through a world “charged with the grandeur of God,” as Merton’s beloved Gerard Manley Hopkins exults.

This interior attentiveness to place is both fundamentally responsible for Merton’s arresting originality and for his contemplative character. Williams dubs Merton’s disposition toward place “priestly,” yet it could very easily be called “contemplative.” At the heart of the life of the contemplative is not an emptiness, a silent lack, or a self-involved examination. The heart of the life of a contemplative is the activity at the root of the word—the Latin verb, contemplari—to consider carefully, to gaze at, to observe. The true contemplative is always beholding something—someone.

❧

Surely by now it ought to have dawned on me that places did not especially matter…

And yet, only a dozen pages later, Merton revealed how a place mattered so much that it has remained embedded in his memory as the site of an irreversible grace acting upon his soul. Corpus Christi Church becomes forever linked with the site of his own salvation. So far from realizing that places do not matter, Merton has perhaps recognized that places matter more than anything.

The humble act of limitation in the Incarnation means that not only can God speak to us through various times and places, but rather that time and place are now qualities native to the eternal and omnipresent God. To be a person means to be a person in a place. The One who sits at the right hand of the father once sat on a boulder on the shores of a lake in Northern Israel. To be human is not a theoretical existence, it is an existence inside a body. And bodies cannot exist in vacuums.

The limitation of Incarnation means that place and person—the raw elements of human living—are now privileged methods of divine communication, maybe even necessary ones. One seeks contemplation of the divine, not by escaping places and people but by situating oneself in the world in such a way that the divinity that has entered into the world shines through in each place and person.

Merton concludes The Seven Storey Mountain with a revelation of the hidden God there all along, guiding this odyssey through place:

“[God] brought you from Prades to Bermuda to St. Antonin to Oakham to London to Cambridge to Rome to New York to Columbia to Corpus Christi to St. Bonaventure to the Cistercian Abbey of the poor men who labor in Gethsemani” (462).

These Literary Cities and idyllic childhood homes are invested in this conclusion with a new identity: a place where God has been.

But Gethsemani, the final stopping-point on his itinerary of his journey with God, Merton knows, is not his final resting place. In his final pages, Merton scolds God: “you have left me in no-man’s land” (459). As Merton ventures back out into the world as a writer, he is unsure of what this means for him as a contemplative. How, after choosing the monastery as the place where he will pitch his tent with God, can he return to the world via writing?

As Williams writes:

“Merton is sure enough of his real place, his real roots, to let some very strange and very strong winds blow over him, to let his understanding grow by this constant recreation in himself of other human possibilities” (47).

Merton was rooted in the real place: his union with God. This union was most nearly fully sacramentalized in the place of Gethsemani, yet it was discovered on a strange journey through strange places. For each space the contemplative Merton entered became place: a place where important words had been spoken, read, and written, a place where his soul had a history with the hidden, radiant incarnate God.

Renée Darline Roden is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame twice over and a faithful expat of Minnesota and Michiana. Renée is an editor and playwright in New York City and an aspiring full-time professional dinner party host. Her writing has appeared in America, Commonweal, and at the Bushwick Starr. She documents sightings of grace in her life at Sweet Unrest.