by Bridget Donohue

“If I take possession of something and have it, that thing has me, too.”

— Romano Guardini, “The Machine and Humanity”

This past summer, while touring northern Italy with two friends, I spent most of my waking moments with my jaw on the ground. The grandeur and beauty were almost unbearable—villages clinging to mountainsides, light falling across tiled roofs. Our last stop, just across the border in France, was the most arresting. Mont Blanc rose behind the town of Chamonix, its summit hidden in clouds. I felt small against something so ancient and grand.

During our journey, my friends and I were reading and discussing Romano Guardini’s Letters from Lake Como. Written a century ago from a village much like the ones we passed through, the letters trace the early signs of a civilizational shift—the arrival of machines, factories, and concrete, and the quiet disappearance of craftsmanship and intimacy with the land.

Guardini’s concern wasn’t nostalgic. He wasn’t longing for a simpler age or hand-hewn beauty. He was naming what he called a new posture of domination—the modern impulse to manage and control rather than to inhabit with reverence and respect. That question led him to wonder what kind of human being could still live meaningfully in the modern world: one who doesn’t retreat from change but enters it with openness, still capable of dialogue—with creation, others, and God.

To illustrate this tension, Guardini contrasts two ways of knowing—two orientations toward the world itself: “The one sinks into a thing and its context. The aim is to penetrate, to move within, to live with. The other, however, unpacks, tears apart, arranges in compartments, takes over and rules.”

As we traveled, my friends and I began to notice in the landscape the very shift Guardini described—and to wonder what it would mean to live in that first way of knowing: to let things stand as they are without immediately analyzing or ruling over them.

At first, I thought humanity might be a lost cause. I couldn’t imagine people engaging creation for the sake of harmony rather than power. But years earlier, I had glimpsed that “sinking-in” kind of knowing—not on a mountain, but in a classroom, during a discussion of Flannery O’Connor’s A Good Man Is Hard to Find.

Flannery O’Connor’s stories have a way of disarming readers before they strike. I led seminars on her work for over thirty years, and they were never easy. Students came in expecting to admire her craft or decode her symbols. They rarely expected to be implicated. A Good Man Is Hard to Find was always the most challenging.

The story follows a Southern family on a road trip from Georgia to Florida. The grandmother—manipulative and self-absorbed—steers the journey toward a detour she insists on. Her small deceptions set the plot in motion. Along the way, the family crosses paths with an escaped convict known as the Misfit. What begins as an ordinary road trip spirals into a violent confrontation, as the Misfit holds a gun to the grandmother and pulls the trigger—forcing a moment of terrifying clarity in her final breath.

In one discussion, a student named Rachael insisted that the grandmother was a Christ figure. I could see why. Perhaps the woman reminded her of her own grandmother, a proper Southern gentlewoman prone to bouts of crankiness. Even in the story’s final moments, as the Misfit levels the gun at her, the grandmother pleads with him to pray. At first she seems sincere. I allowed the conversation to unfold, even as it veered toward tidy moral conclusions. Eventually, I proposed that if anyone resembles Christ in the story at all, it might be the Misfit—albeit in a dark and unsettling form.

Even his gestures seem to shadow the shape of redemption. He stoops to draw in the sand as he speaks of Jesus raising the dead. His words are defiant, but his knowledge of the Gospel runs deep, as if he can’t escape the story he rejects. The grandmother’s pleas for him to pray turn eerily desperate and self-serving. When she finally reaches out and calls him “one of my own children,” the gesture is both absurd and illuminating—a flash of recognition that collapses the distance between them.

In the end, he becomes the unwilling agent of grace—the one through whom the grandmother finally sees herself as she is. When the Misfit strips away her pretenses, the students realize that the character they had sympathized with all along wasn’t harmless at all. She was a fraud, and they had been taken in.

Rachael, visibly angry, left the classroom. The room was silent until the bell rang and class was dismissed. Later that day, she confronted me and said, “I think you’re right, and I don’t like it.”

What happened in that classroom—though Rachael herself may not have named it—went beyond interpretation. It was a shift from trying to master the text to standing before it as something that could master her, unsettle her, demand something of her. The story wasn’t something to be unpacked. It was a presence to be reckoned with.

Rachael’s initial unwillingness to simply encounter the story was not unusual. It reveals a pattern woven through our modern way of living. We are trained to manage things, to keep them under control—to turn even an unsettling story into something safe and useful. Rather than letting a text confront us, we reduce it to a lesson. Rather than receiving reality, we analyze it, categorize it, and dominate it.

This impulse runs deeper than one classroom. It’s the very habit Guardini warned about—the refusal to let things stand on their own terms. He returns to this contrast in a later letter, now with a broader lens. He’s no longer just contrasting ways of knowing; he’s tracing a cultural shift that began with the rise of modern technology: “The old way let things be what they were. The new way tears them apart and arranges them in compartments—understanding in order to control.”

And that’s where the heart of the matter lies—not just in how we read a story, but in how we engage the world itself. Do we approach the world to live with it—or to take it apart in order to dominate it?

This kind of knowing is always a risk. It doesn’t end in tidy conclusions. It’s disorienting, sometimes painful. But it is personal. In Rachael’s case, she wasn’t merely developing intellectual skills. She was being formed in how to stand before something real—with humility, attention, and the willingness to be changed.

Her reaction—“I think you’re right, and I don’t like it”—was not evidence of failure. It was evidence that she had come into contact with what Guardini calls the given: the real, the untamable, the not-yet-arranged. And for a brief moment, she let it be what it was—a mirror, not a lesson.

Rachael was willing to enter that sacred space, no matter how uncomfortable. Would that all students had the same courage.

Rachael graduated from high school and went on to marry and raise a beautiful family. She traveled the world with her husband and children and kept a blog called What If We Fly, where she wrote with fierce honesty about joy, motherhood, beauty, and suffering. She died of colon cancer in July of 2023.

I believe she came into the classroom already disposed to this kind of learning. But I also hope that something she encountered in that moment took root—something that helped shape the way she lived, and maybe even the way she died. She didn’t approach life as a problem to solve. She entered it fully—paying attention, letting herself be changed.

Guardini never met her, but I think he would have recognized her. He was writing about machines; she was encountering a story. But the question was the same. She lived the kind of knowledge he tried to name—the kind that does not take possession of the world but lets it be: wild, luminous, unbearable, and good, just like Mont Blanc.

And because of Rachael, I know that humanity is not a lost cause. It’s possible to live one’s entire life with reverence rather than manipulation and power. I hope I can imitate her.

Bridget Donohue spent 35 years teaching at a private high school, where she led seminars on Scripture, history, and literature and served as an advisor for curriculum development. After retiring, she founded Project Dignity, where she now serves as the Executive Director, helping refugees build new lives in the United States. Bridget is also an editor for Veritas Journal. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, strolling the neighborhood with her mission-driven puppy, Miss Maudie, and cherishing time with friends and family.

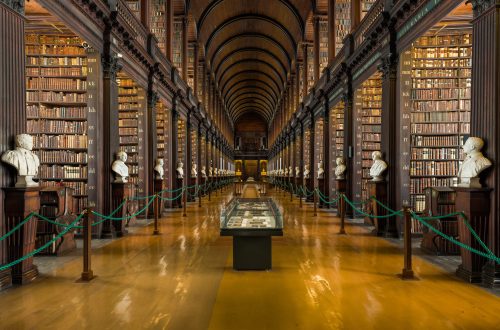

header image: Jon Balsbaugh, “Untitled,” French Alps (2025)

One Comment

Abbey von Gohren

I am so happy to see this up here, Bridget!