by Patrick Tomassi

The Hundredfold and the Restless Heart

In 1954, the Italian priest Luigi Giussani was teaching in a public high school in Milan. He saw that, while his students knew the “right answers” of the Catholic faith that was so much a part of Italian culture, it had nothing to do with their lives. He began meeting with some of these students to help them discover “the relevance of faith to daily life.” Giussani used to relate to his students an episode in the Gospels when Jesus says, “Whoever follows me will have eternal life and the hundredfold here below.” (Mt. 19:29) And he would say to them, “If you do not desire eternal life, I understand you, because you have little imagination; but if you do not desire the hundredfold here below, then you are fools.”

I teach at a small Classical Christian school in Portland, Oregon. Once, several years ago, I was giving a talk to the boys at the school, and I started with a related question: “Do you want to be happy?” I had perceived a budding cynicism in a few of these boys, and wanted to try to help them recognize it. This turned out to be a mistake, because one of those cynical boys realized he could completely derail me if he blurted out “No!” I asked him later why he had done it, and he told me that he didn’t care about happiness; he just wanted to have fun. The conversation went nowhere, but I think his desire to have fun was simply a facet of this boy’s need to be happy.

I do not mean happiness in the sense that it is often used – a fleeting, ephemeral feeling, an emotion that happens to you and then goes away. Nor am I talking about the sort of happiness that comes from wealth or fame; one doesn’t have to look far to see that the rich and famous are often the most unhappy. Instead, I am referring to the deeper sense of happiness that Jesus describes as “the hundredfold.” St. Iraneus said that “the glory of God is man, fully alive.” The glory of God – the reason that Jesus comes to Earth – coincides with our being fully alive. Giussani put it this way in The Religious Sense: “Life is hunger, thirst, and passion for an ultimate object, which looms over the horizon, and yet always lies beyond it. When this is recognized, man becomes a tireless searcher.”

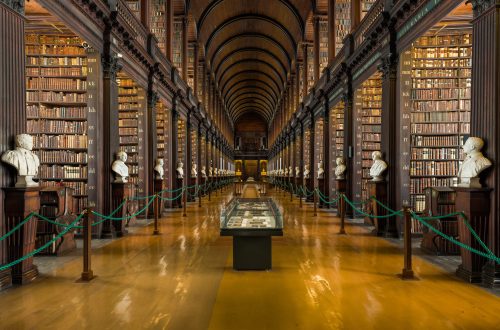

At my school, we talk about this as the desire for truth, goodness, and beauty. It might sound abstract to say “I desire truth.” But it only takes a few minutes with a little kid to see that they have an irrepressible desire to understand everything around them. This is why little kids ask so many questions. The notion of justice can be similarly abstract. This summer, we have seen massive protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. I went to report on the protests in my hometown of Portland, which have sometimes been destructive and violent. The people I spoke with, both those supporting the protests and those who believed they were misguided or had lost their way, shared the desire for a more just society. The same goes for beauty. A couple years ago I was driving home from Seattle on a summer evening. It was partly cloudy, and the sun was setting over the Olympic Mountains to my right. The clouds were orange and purple and pink, and yellow beams seemed to jut out from over the mountains, reflecting off the buildings. I nearly got into a car accident because it was so hard not to stop and marvel at the beauty. You see a beautiful landscape, or a beautiful person, or a beautiful painting, and a longing surges up inside you without your permission. You want it to be infinite. You want to possess it.

Quarantine and the “Everydayness”

There is a core of desires and needs that all of us share, which scripture calls “the Heart”; we all desire truth, beauty, goodness, justice, freedom, friendship and love, meaning. These are what make us human, and it is for the satisfaction of these desires that Jesus comes. On my own, I’m not capable of finding a love that can satisfy me. This is why Augustine writes “You have made us for yourself, Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.”

During the quarantine this spring, I made a point of calling and checking in with each of the boys in the school. Some conversations were quick; others pushed an hour in length. While some of the boys discussed good experiences and moments of growth, the themes that ran through almost all these calls were loneliness, boredom, frustration, and a loss of motivation. Each of these experiences points back to the heart in some way. The pain of losing someone I love pushes me to realize that I want a love that can’t die. It would make no sense to talk about loneliness as a bad thing, as a difficulty, if I didn’t desire friendship. When I’m bored, when I lack motivation, I can see more clearly that I want to be captivated by something; when I love what I’m doing, when I’m fascinated by it, I don’t get bored.

But rather than face the needs of our hearts, we often find ways to avoid them. I found a few weeks into the quarantine that I was spending a lot more time on my phone than before. I started to delete the apps that I wasted the most time on, only to find that I would switch to other apps or other distractions, and waste the same amount of time. The apps —or for many of my students it’s video games — provide an easy solution to the problem of boredom; if I’m bored, better I not even realize it.

In southern novelist Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, the title character, Binx Bolling, goes to the movies to escape what he calls the “everydayness” of life. But at a certain point in the novel, he embarks on what he calls a “search.” “What is the nature of the search? you ask. Really it is very simple, at least for a fellow like me; so simple that it is easily overlooked. The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. This morning, for example, I felt as if I had come to myself on a strange island. And what does such a cast away do? Why, he pokes around the neighborhood and he doesn’t miss a trick. To become aware of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.”

But most of us, most of the time, are not on “the search.” We choose comfort or entertainment over our desire to be truly satisfied. Like Binx, we numb ourselves to “the everydayness” with movies, shows, and games, with social media, or with chilling with friends. I think the reason is fairly simple: to be on “the search” is hard. It’s uncomfortable. It’s not pleasant to realize that I have a desire that isn’t satisfied. But it is also more worthwhile—unless I am attentive to my desire, unless I allow myself to experience the discomfort of it being unsatisfied, I will not recognize what I long for when it comes my way.

Education and Human Flourishing

Education, fundamentally, is about human flourishing, and in order for an education to succeed in engendering flourishing, it is necessary for it to reach the heart. It’s not enough to have a perfect grasp on Augustine, or to write a flawless essay on To Kill a Mockingbird. When I discover that the questions Augustine asks are my questions, or that Atticus Finch and I have something fundamental in common, human flourishing starts to happen. When we ask these questions and address these needs with those who have done so across time, when we seek to understand, to get to the bottom of things, we become more fully human.

Due to the pandemic, the return for many of us to remote learning, and the unrest in our society, these needs are more exposed than normal. And at the same time, many of the ways that we might respond to them are not possible — we can’t spend as much time with the people we love; we can’t travel to exotic places; we can’t do many of the group activities we enjoy.

The easiest way to react to this circumstance would be to spend our time being distracted by various little things. In The Screwtape Letters, the senior devil, Wormwood, tells his nephew Screwtape: “The Christians describe the Enemy [Christ] as one ‘without whom Nothing is strong.’ And Nothing is very strong: strong enough to steal away a man’s best years not in sweet sins but in a dreary flickering of the mind over it knows not what and knows not why, in the gratification of curiosities so feeble that the man is only half aware of them.” Our technological life has made this more easy than ever; stream Netflix or play video games. “Go to the movies” with Binx Bolling.

It is a much harder thing to be on “the search,” to put aside the things that distract us in pursuit of the hundredfold. I find that it is not something I can do on my own – I need to have friends who are on the search, who realize that life is about more than being comfortable.

But it only takes a momentary step outside the “everydayness” and onto the search to realize that it is also a more life-giving thing.

Patrick Tomassi teaches math and science at Trinity Academy in Portland, Ore, where he also leads a film club for high school students. He spends the rest of his time writing about education, film, music, and literature, hiking in the Pacific Northwest, and perfecting his barbeque ribs recipe. Patrick helps to organize the annual New York Encounter, and is a contributing editor for Veritas Journal.

Interested in reading more? Revisit Matt Axvig’s “The Moviegoer: Suburbia, the Search, and Binx Bolling’s Existential Homelessness,” or Margarita Mooney’s “Tradition and Authority in Luigi Giussani’s Education Method,” both in Veritas Journal.

Header Image: The Olympic Mountains seen from the High Divide, AlphaOrionis42, shared by permission under CC BY-SA 4.0

One Comment

Pingback: