by Bridget Donohue

Several years ago when a student told me she thought I lived inside the Book of Revelation, I was intrigued. Revelation is not a text that gives itself away easily; its veiled language and wild imagery invite you into a world of layered meaning, where symbols evoke more than they explain.

Too often, people try to reduce Revelation to a riddle to be solved, as though the beasts and bowls, trumpets and thrones could be decoded into a neat timeline. To be sure, apocalyptic language has a logic to it—a symbolic grammar that can and should be studied, much like one might analyze poetry or music. Understanding the meaning of those symbols is part of engaging the text; in some ways, Revelation is like a puzzle. But it can’t stop there. Once you’ve “figured it out,” you don’t simply close the book, heave a sigh of intellectual satisfaction, and move on. To do so would be like pulling apart the pieces of a great work of art and never putting them back together. Apocalyptic writing invites something more visceral and even transcendent.

Isaac Newton captured something of this in his posthumously published essays, Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John. He compared reading Revelation to understanding a steam engine. To grasp how it works, you take the engine apart piece by piece, examining what each part does and how it fits into the whole. But you don’t leave it that way—disassembled and lifeless. You put the engine back together, ignite the generator, and set it in motion. The knowledge of how it works deepens your appreciation for what it accomplishes and transforms your experience of the journey.

This principle applies not only to texts and steam engines but also to art and music, where understanding the parts reveals the beauty of the whole. I saw it play out once with a group of eighth-grade boys when I introduced them to Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. At first, they were unimpressed and even bored, giving me that look reserved for worn out teachers who are trying too hard. But then we took the time to study the music. We examined the score, broke it down, and analyzed the intervallic relationships, harmonic structure, and the way each movement builds on the last. It was like taking apart Newton’s steam engine to see how it worked. When I played the piece for them a second time, everything changed. They were mesmerized, fully absorbed, some even conducting with their hands waving about in the air. Understanding the parts transformed their experience of the whole, transporting them into a different world.

Revelation works like this. Its strange and symbolic world invites you to take it apart, to study its patterns and rhythms carefully. But then it invites you to put the pieces back together and discover it all over again—not just as a puzzle to be solved, but as an experience to be lived. It doesn’t explain so much as it reveals, and what it reveals is always greater than the sum of its parts.

But what does the experience of living inside Revelation feel like? To answer this, we need to look beyond its symbolism and see how it reshapes our understanding of time itself. Its chiastic structure, where themes mirror and echo each other in reverse order, reflects a cyclical rather than linear view of history. Revelation forces us to inhabit a world where time is fluid, bending and folding instead of progressing in a straightforward, fixed path.

This scrambling of time is not unique to Revelation. Other works, like Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, employ similar techniques. In Our Town, Grover’s Corners, the small fictitious New Hampshire town, becomes more than itself. It stands for all towns by folding past, present, and future into a single, universal place. The play’s folding of time evokes a sense of regret—that we fail to truly see life as we live it. Wilder suggests that perhaps only saints and poets recognize the fullness of life in the moment, while the rest of us realize too late what we’ve missed.

Revelation also collapses time, but in a slightly different way. Its literary patterns fold the past and future onto the crucifixion and resurrection—the definitive moment of history—and define that moment as the present. It insists that regardless of the age we live in, our present is saturated with the victory of that event. Where Wilder leaves us with the ache of what was missed, Revelation offers something different: the assurance that the fullness of God’s triumph is already at work in every moment, moving us from despair to hope.

This folding of time, then, is not just a literary device—it reshapes how we live. Revelation invites us into the overlap, the space where heaven and earth meet and the kingdom is both here and still to come. Think of a Venn diagram: two circles—heaven and earth—overlapping in a middle space filled with the fullness of God’s glory. In this space, hope becomes something more than a fleeting wish. St. Peter describes it as being ‘born anew into a living hope—a gift rooted in God’s action, alive and transforming us. It is not something we create ourselves, but something we are given. Even so, we must choose to live in it and let it shape how we see the world.

“Esther’s” story illustrates this beautifully. As we studied Revelation one year, she was in the midst of deep suffering, spiraling into such darkness that she had stopped dancing, her greatest love. The thought of placing her hope in some distant future event was unsatisfying and even repugnant to her. At the same time, she strove to understand how Revelation spoke to her particular experience of suffering. One day, after returning home from school, Esther made what she later called a reckless decision. She turned on a favorite tune, and she danced. When she realized she was dancing again, she wept. And then she said this:

I didn’t dance again because that day had come; I danced because I finally believed it would.

In that moment, Esther got a sense of what it feels like to live in the middle of the Venn diagram, where the promise of God’s future victory breaks into the present. Her decision captures the paradox of hope: it often asks us to act in ways that seem unreasonable, trusting in a reality we can’t yet see. It compels us to live as though the promise of victory is already true.

And I love that Esther calls this hope reckless. It surely is. There is absolutely no reason she should dance—in some ways, it’s a foolish move. What will happen to her struggles? Will anyone see and understand them? Will there be any justice? Yet the gift of hope overwhelmed her, and she plunged into the reality of God’s victory with full abandon.

Revelation challenges us to see hope as more than a fleeting feeling or a distant wish. It is a gift and a way of being—a bold, even reckless, habitual orientation toward the moment when God will be all in all. This hope defies logic, urging us to live with confidence and act not because the day has fully come, but because we believe it will. To live inside Revelation is to inhabit the overlap of heaven and earth, where the future promise of God’s glory transforms our present. The power unleashed in the death and resurrection of Jesus reverberates across all time, calling all of us, not just the saints and poets, to trust in its truth—even in this very moment.

Bridget Donohue spent 35 years teaching at a private high school, where she led seminars on Scripture, history, and literature and served as an advisor for curriculum development. After retiring, she founded Project Dignity, where she now serves as the Executive Director, helping refugees build new lives in the United States. Bridget is also an editor for Veritas Journal. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, strolling the neighborhood with her mission-driven puppy, Miss Maudie, and cherishing time with friends and family.

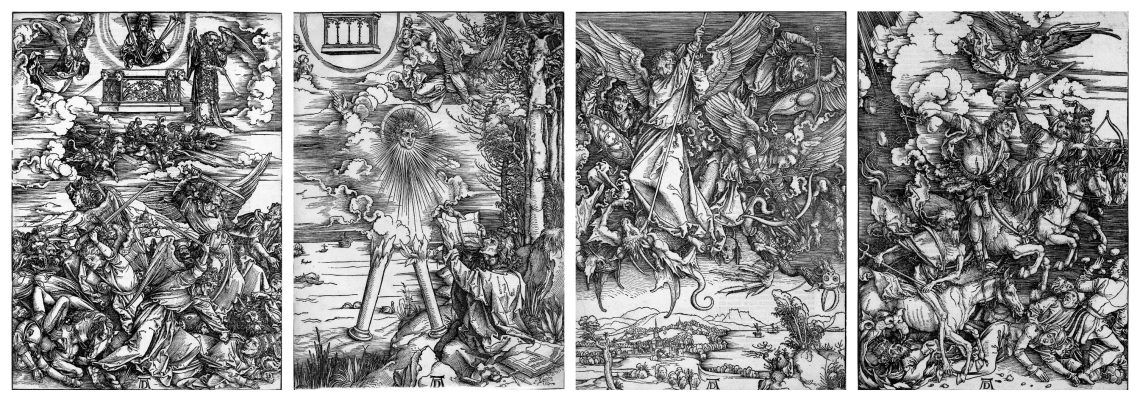

header image: Albrecht Durer, Four Woodcuts from his series “Apocalypse with Pictures” (1498), in the public domain.

One Comment

Henry Lewis

I love this essay. True reality is exactly so. Beautifully expressed and wonderful to read. A blessing.