by Jon Balsbaugh

In school we are taught that valuable learning is the result of attendance; that the value of learning increases with the amount of input; and, finally, that this value can be measured and documented by grades and certificates.

– Ivan Illych, Deschooling Society

Growing up in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, I learned how to fish the trout-rich tributaries of the Cascade Range almost without trying. I acquired those fishing skills almost as one acquires language, through imitation, tips, and trial-and-error. I still get back there from time to time. Though no longer as adept at wading, cliff climbing, and boulder hopping, I can still sometimes catch my limit of rainbows before breakfast even when no one else is getting bites. Yet my father and grandfather never told me I was getting a B- in trout fishing. Neither ever gave me an 88% in spinner retrieval or a 75% in hook selection and baiting. What they did was take me fishing, show me a few things, provide feedback, and let me go off on my own when I wanted to.

- “See the rock right there? The fish will be just on the other side. Cast over the top of it and let it drift into the hole.”

- “That was a little too quick on trying to set the hook. Let it nibble, then wait for it to take a stronger bite.”

- “Oops, make sure your line is tight.”

- “Nice fish!”

- “Why don’t you take the next hole down, and I’ll go upstream. Be back at the car by 10.”

Their feedback was equal parts information, affirmation, and criticism; but these were the kind of tips I needed — limited, specific, timely, and contextual. Comments like these built a bridge for me between watching my father and grandfather fish and fishing on my own — a bridge between imitation and trial-and-error.

Formal education should be no different. What we call “learning a lesson” is mostly a matter of imitation, and homework and tests are exercises in “trial and error.” Good coaching and feedback provide the “tips” necessary to bridge the gap between the two. But none of this requires a “grade.” Grading is not the same thing as evaluation. Though grades are a part of the system, every meaningful aim of education could be accomplished without them. In fact, studies have shown that grades negatively impact learning (especially for boys) and exacerbate mental health issues (especially for girls), reinforcing what most classroom teachers can readily observe.

Grading vs. Narrative Assessment

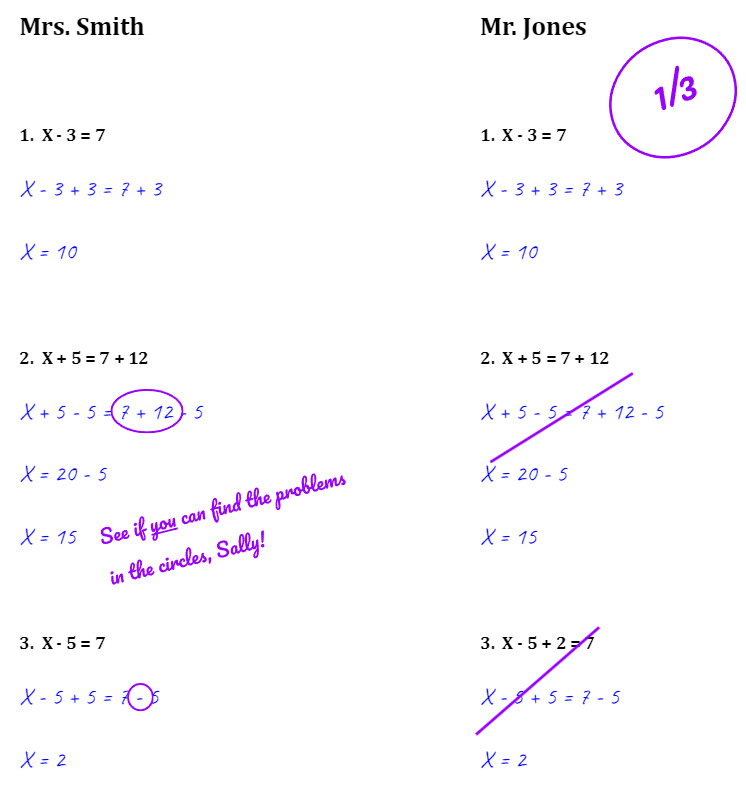

Consider the two sets of homework evaluations below:

Which of these would be more useful to Sally’s dad when he tries to help his daughter at home? Which process is going to help the teacher better understand how Sally works? Most importantly, which will actually help Sally learn how to find X?

With Mrs. Smith’s subtle tips, Sally will likely be able to identify her mistakes on her own. Even if she can’t, she could go over her homework with one of her parents, see Mrs. Smith after class, or even ask a friend to help her.

The only reason for preferring Mr. Jones’ approach to that of Mrs. Smith’s is that it might have taken Mrs. Smith a little longer to evaluate the stack of papers she took home that night. Imagine, though, a world in which Mrs. Smith does not then have to enter that 1/3 into a grade book, create “entrance tickets” and “exit tickets” for each student for each day, take a phone call from Sally’s dad concerned about the impact of a 33% on her grade and wondering whether Sally needs tutoring, or sit down with Sally after school to go over the problems she missed. She might even be ahead in the long run.

So why do we seem to want grades?

The Modernist Bias Towards Numbers

Despite the superiority of Mrs. Smith’s approach, parents, teachers, and students alike are often more comfortable with precise numerical scores. They feel objective. They feel scientific. They even feel right — a protection against the danger of a teacher’s bias. We have been taught to associate numbers with objectivity and words with subjectivity, and we have been taught to value the former and fear the latter.

But numbers are not more real than words.

On the contrary, the idea that a number like 82.3% could serve as a summary of student performance is the real problem. It cannot. What a student has learned is demonstrated in the skills, knowledge, understanding, and habits of mind he has acquired. Those skills are best understood linguistically, not numerically.

As any veteran teacher can tell you, there are dozens of ways in which a student can “get” an 82.3%. No B- is the same, and some are very different indeed.

- Bridget is a brilliant thinker with little care for the details. 82.3%

- Devante is a minutiae master who regularly fails to see the forest for the trees. 82.3%

- Cormac was sick for a third of the semester and missed some core instruction. 82.3%

- Alicia knows all the material but doesn’t consistently turn in her homework. 82.3%

So here is the critical question concerning grades: “In any of these cases, does the 82.3% add anything of value to the sentence before it?”

The same question could be asked of end-of-term assessments as well. What if, given a school with a clear sense for the intellectual skills and habits of mind it wants to form in its students and a course strong set of course goals, a teacher could provide parents with something like the following:

Sally seems to understand most of the core concepts of first-semester Pre-Algebra. She demonstrated that she knew how to factor, follow the order of operations, evaluate and simplify algebraic expressions, combine like terms, and solve equations. When we introduced fractions, however, she struggled to grasp what was going on — especially when they were combined with variables in an equation. While she can make simple mistakes through inattention, she is usually able to identify her own errors with a second look. Intellectually, Sally is engaged in mathematics, intrigued by the puzzles presented in Pre-Algebra, and often raises new and interesting questions.

As above, “Does a B+ add anything of value to this description?”

If the answer to this and the previous question is, “No,” then maybe we should stop tacking on a grade or percentage at the end of an evaluation just to baptize it with a false sense of objectivity. At best, a grade is a gross approximation of a student’s knowledge and skills.

Still, we seem to be so used to grades that we struggle with the idea of giving them up, especially when the alternative might be to rely upon a teacher’s professional judgment put into words.

Overcoming the Spectre of Subjectivity

As an administrator, if a student got a B in art, I could almost count on a grade appeal. Part of that appeal would usually include the criticism that grading art was an especially “subjective” exercise. Because the skills involved in mastering the techniques of art are difficult to quantify, a teacher’s statements about them are automatically suspect. Ironically, it is in the realm of the arts where the objectivity of expert judgment is most clear.

One need not even go that far to establish the objectivity of art assessment, however. Say the students have been given a task to copy a portrait. It is objectively the case that some copies are better executed than others. The differences can literally be seen. Even someone completely unschooled in the language of the visual arts can tell the difference between excellence and competence. Consider the two samples below:

Even an amateur can see that the copy on the right is objectively better executed than the copy on the left. If we were to add twenty more student copies, the non-expert could probably even sort them, group them, and assign each a “grade.” The value of the master artist or master teacher, then, is to be able to say something meaningful about the differences — to put the differences into words.

To a more studied eye, the piece on the right has a better command of line, shading, and blending. It demonstrates stronger draftsmanship and attention to detail. It is more realistic and less abstract. And even if those things cannot be easily quantified, they are true and objective assessments. They are made based on the artist’s training and the tradition of the visual arts. In our current system, an art teacher might be forced to assign a “score” for each of the criteria or use some rubric to arrive at a grade, but she would know that the number is not the reality.

And what is true of art is true of the other disciplines as well. Consider the thesis statement of a paper. Some theses are objectively more precise than others. Some objectively probe more deeply into the topic assigned. Some are objectively more nuanced. Can we assign a percentage on “nuance”? No, but an experienced writing teacher knows it when he sees it and knows how to talk about it. Here again, it is a matter of trained judgment and experience.

Think about Sally’s math homework. Is she failing to learn the material to such an extent that she should get a 33% on that assignment, sending alarm bells ringing? No, she should not. She has a solid grasp of the basic process involved in isolating the variable, but she keeps making little mistakes. Does she need to address those? If she wants to consistently get the right answer, then, yes, she does. Is that the same thing as abysmal failure? No, it is not.

If we are to free our children from the tyranny of grades and their negative effect on motivation and performance, we must first free ourselves from the tyranny of numerical objectivity.

This article is part one of a four-part series on grades and grading.

- Part I: “The Industrial and Modernist Roots of Grading”

- “Part II: “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Assessment”

- Part III: “Rigor, Grades, Challenge, and Leisure”

- Part IV: “If Grade We Must”

Jon Balsbaugh is the founder and chief editor of Veritas Journal and owner and operator of Kairos Educational Consulting. He lives in South Bend, IN with his wife and five children. Mr. Balsbaugh has been involved in classical education for over twenty-five years. He enjoys seeing the world through the lens of his three primary hobbies: fly fishing, foraging, and photography.

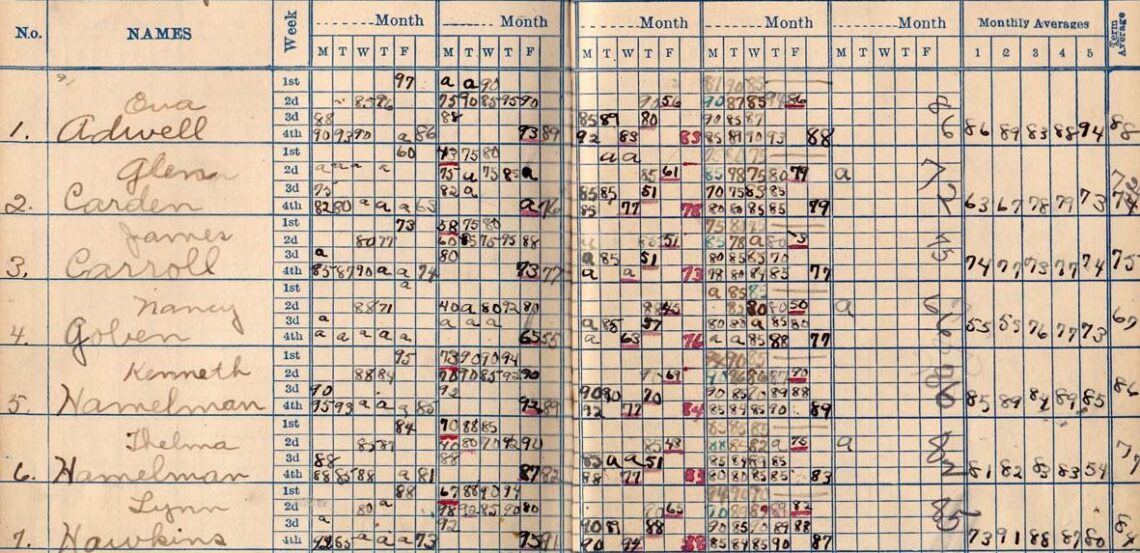

Header Image: “1923 Gradebook,” Cat Sidh (CC 2.0) (cropped)