Moderated by Dr. Holly Peterson, the panel of Dr. Stanley Hauerwas, Archbishop Christophe Pierre, and Jon Balsbaugh rethink education at the end of an epoch during a session at the 2019 New York Encounter. Click above to watch the video of the entire panel, or read below for an excerpted transcript of Dr. Peterson’s exchanges with Jon Balsbaugh, the president of Trinity Schools and the editor-in-chief of Veritas Journal.

Holly Peterson (Moderator): Dr. Hauerwas in his video notes that the education of the heart which Giussani says is the locus of our primary needs – this is the place where my “I” is my “I.” So this education creates a ‘centered self.’ From your perspective as an educator, how does education cultivate the heart – how does it help the heart to flourish?

Jon Balsbaugh (President of Trinity Schools): I think that there’s a really important distinction there between the ‘centered self’ (in the way that Dr. Hauerwas is talking about it) and what he warned against, something I think it’s easy to confuse that with, which is an ‘independent self.’ The first is to be centered within total reality and the second is to try and find a way to be entirely centered within yourself – autonomous, free, and unmoved. The first of those is a noble human goal; the second is probably a dangerous path to spiritual isolation.

So I think that another way to ask this question would be: “What can education do to help people choose that first path over the second?” And I think it has to start with the aim of education. I think we have to have an aim of education that Jacques Maritain calls “human awakening” – not SAT scores, not college placement, not even graduation rates and literacy (as important as those latter two are) but human awakening to reality.

Once, as educators, we have that aim and adopt it, there is actually a fairly simple way to carry it out. I say ‘simple’ because it is. But it’s also one of those simple arts that takes a lifetime to master – and that is to never give an explanation to a student unless they have first encountered the reality you are explaining.

I’ll give an example. For more years than I can remember I taught 8th grade boys literature and composition. And that meant that in the cycle of my life, come springtime, it was my job to teach these young 13-14 year old boys the fine art of poetry. In the early years I cannot remember what I did to introduce the topic, but I remember that it was frustrating and unproductive. And I came away thinking, “They have no aptitude or even instinct for poetry in the way I appreciate it.” (And I’m sure they felt that.)

Then one year I realized, “They don’t know why a poet would write a poem. They have not had an encounter with the world that aroused that poetic urge in them.”

So I said, “Alright boys, we’re going to go outside.”

This was when I was teaching in Minnesota, and one of the things that corresponded with the spring was ‘the great thaw.’ Surprisingly (for someone who did not grow up on the tundra), beneath that layer of snow and ice was an almost perfectly preserved layer of fall leaves. Some of them were still

And that smell is so pungent and so particular and the sense of smell so connected to memory that inevitably they went back to something in the fall, a very particular event –

Then I said, “So look around. The buds are on the trees, the birds have come back, the grass is greening – but you hold in your hand

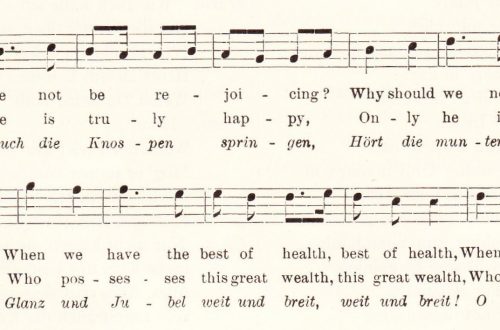

Then we went back inside and talked about the spring and the fall and what they meant and what they felt like. We put some nouns and adjectives up on the board and we wrote a little poem together. Then at the end of that

And that really is a fairly simple method, but it provided a better introduction to poetry than anything I could have written on the board, any introduction they could have read in a textbook.

This method – never explain something before a student has encountered it – doesn’t apply just to poetry. You can apply it to science, to art, even to mathematics. I was talking to another educator here this week and his approach was that every chemistry class should start by burning something. That’s a similar instinct. And I think when you do that with students you do position them to be more centered in the world – in the world of things and the world of people. And you give them a chance to avoid that isolation or radical independence.

HP: How does wonder generate us – which is the opposite of Dr. Hauerwas’s understanding of things that might consume us? How does wonder ‘generate’ our hearts?

JB: I should probably say a little something here about what we mean by wonder. I think in typical speech we tend to think about driving to the Grand Canyon or going up to the Alps and have some encounter with the sublime and our soul sort of resonates with that. But then it’s over and then we go home. Those experiences are very important to the human condition. They can refresh and even ennoble us. But what the ancients meant by wonder was something a little different. Aristotle, Plato, the others…when they talked about wonder or Thalmuzein, they were talking about something that was intrinsically generative. It led immediately somewhere. So wonder for them was actually more like a deep curiosity or perplexity. Or even

Now, what does all that have to do with the education of the heart? There’s a great line from TH White’s The Once and Future King (which is a great book on education, by the way). In it, Merlin the wizard is trying to console Arthur, his protégé and young student, in a moment of darkness for him. He says, “The best thing for sadness is to learn something. That is the one thing that never fails.”

Now if we were just talking about the academic life I am absolutely going to disagree. If somebody comes up to me and says, “I’m sad,” I’m not going to say, “Sit in a classroom for eight hours.” That’s not productive. But if we connect this experience of wonder to an investigation of the world and a dialogue with the world, I think that Merlin may be onto something there. Because when we wonder – when we encounter that moment of confusion or curiosity – the world is suddenly not a neat and tidy and self-contained place.

Not all sadness is bad and not all sadness is the same. But there is a kind of sadness that comes from being disconnected from the things of the world. I think it has something to do with what David Brooks was talking about last night with acedia, Or what the panel was talking about in terms of loneliness earlier. This notion of things being ‘boring’ is wrapped up in that. So maybe this is a particular kind of sadness that wonder can address. Because when we wonder the world suddenly becomes a different place than it was five minutes ago. It becomes more open. We make some contact with mystery. Every moment of wonder seems to bring with it a kind of awareness of the freshness and vitality of the world as it was when we were children. That can’t help but nourish our heart and center us in a certain way.

I’ll say one other thing on behalf of wonder and that is its connection to friendship. C.S. Lewis wrote somewhat famously in The Four Loves about what it took to make a transition from being mere companions to being genuine friends. He said that happened when two or more people realized that something that was deep in their heart, either a unique burden or a unique delight, was shared by another person. So the actual moment of friendship began when two or more people said, “What? You too? I thought I was the only one.”

I think even in a formal academic environment those moments of wonder that you experience in a classroom sow the seeds for friendship. Maybe at first the classroom or a group of friends becomes a community of learners but eventually that becomes community in other ways as well.

Some of my former students were here and I wanted to make sure this was true. So I asked them, is this true? Your experience of wonder, did it make you better friends? They paused for a moment and said, “Yeah absolutely. We became friends through those kinds of encounters.” (Somewhat comically they also reminded me that there’s a flip side to this. So if you discover in a burgeoning friendship or a relationship that that person does not share a delight for something that is dear to you it almost becomes an obstacle to friendship. So if I find out somebody absolutely hates Bob Dylan, I’m not sure we can continue here. Where can we go from that ground?

At any rate, experiences of wonder both shape the soul in a certain nourishing

HP: The Archbishop just talked about the need for a witness. What is the role of the teacher in evoking wonder and thinking about the teacher as a witness? How does the teacher grow in wonder?

JB: I think a teacher absolutely has to be above all else a witness to these things. A teacher has to bear witness to a love of the world and a love of not just their subject. Frankly, nobody really should love a ‘subject.’ Your love should be directed to the reality that lies beneath the subject. I really don’t think anyone should love teaching chemistry. They should love chemical reactions and then wish to share that love with other people. So the act of bearing witness is fundamental to being a teacher – more important than any technique or anything that we could point to about how to teach.

HP: Dr. Hauerwas agreed with Fr. Giussani in that education is about learning, leading us to the truth – the truth of reality and of ourselves. To be happy with and

JB: That is such a good question and such a good point Dr. Hauerwas made. At

But I would add that there has to come a time in the education of the heart that the heart turns outward and develops a habit of active love.

One of my favorite poems is “Love Calls us to the Things of This World” by Richard Wilbur. He’s an American poet. In the poem, the poet wakes up in the morning. (He’s in Rome. We know that biographically.) He wakes up in the morning to the cry of pulleys. The laundry is being put up from the wash. He looks out the window and sees the blouses and the bedsheets and the smocks passing by. And for a moment he mistakes them for angels, for celestial beings. He has a moment of rapture. But then, as always happens in these moments, reality begins to come back in rather quickly and he remembers his embodied existence. He remembers everything he has to do in the day. And the poem says that his soul cries out, “Let there be nothing on earth but laundry / Nothing but rosy hands in the rising steam / and clear dances done in the sight of heaven.”

I think we’ve all been there. We’ve had those transcendent experiences and maybe for some this weekend is one of those. “Let there be nothing on earth but jazz and poetry and discussions and the constant buzz of Italian conversation.” Maybe for some of

In a certain

I want to read the end of the poem. This comes right after the cry, “Let there be nothing on earth but laundry.”

Yet, as the sun acknowledges

With a warm look the world’s hunks and colors,

The soul descends once more inbitter love

To accept the waking body, saying now

In a changed voice as the man yawns and rises,

“Bring them down from their ruddy gallows;

Let there be clean linen for the backs of thieves;

Let lovers go fresh and sweet to be undone,

And the heaviest nuns walk in a pure floating

Of dark habits,

keeping their difficult balance.

I have always admired that poem and thought it had something to do with living well. As I was reflecting on this weekend I also realized it had to do with doing education well. Because if we’re going to educate the heart there is a kind of difficult balance to be kept.

The first part of that, that Dr. Hauerwas alluded to, is honesty. The first part of the balance is getting everything in and being honest about it. Thieves, lovers

But on the other side of this difficult balance is love – love in the face of honest reality. How do we come to say, “Let there be clean linen for the backs of thieves?”

You can imagine, as I have been meditating on this ahead of the weekend … to show up and see the work of APAC was just very powerful. That first night’s opening. What a testimony to “Let there be clean linen for the backs of thieves.”

Somehow, in what we do as educators, we have to help them keep that difficult balance. I really do think in education, if we can embrace human awakening and remember some of these simple methods (like “Never explain anything before you encounter it”), and if we can, as you said, Holly, bear witness to a love of the world (because there is no method for that – there’s only witness) …. if we can bear witness to our students that we love the world, that we love the reality beneath our subjects, that we love them and that ultimately the love of God surrounds all of that, education can be a powerful ‘something to start from.’

One Comment

Matt Axvig

I’m grateful for the inspiring vision here. As another follow-up to references in the talk (alongside the Wilbur poem), I thought I’d share a passage from Lewis’ “Four Loves”.

Here’s a short paragraph contrasting friendship with romance:

When I spoke of Friends as side by side or shoulder to shoulder I was pointing to a necessary contrast between their posture and that of the lovers whom we picture face to face. Beyond that contrast I do not want the image pressed. The common quest or vision which unites Friends does not absorb them in such a way that they remain ignorant or oblivious of one another. On the contrary it is the very medium in which their mutual love and knowledge exist. One knows nobody so well as one’s ‘fellow.’ Every step of the common journey tests his metal; and the tests are tests we fully understand because we are undergoing them ourselves. Hence, as he rings true time after time, our reliance, our respect and our admiration blossom into an Appreciative love of a singularly robust and well-informed kind. If, at the outset, we had attended more to him and less to the thing our Friendship is ‘about,’ we should not have come to know or love him so well. You will not find the warrior, the poet, the philosopher or the Christian by staring in his eyes as if he were your mistress; better fight beside him, read with him, argue with him, pray with him.

–C.S. Lewis